Getting Alabama to come out on top of Google’s own search results for its high-tech data center took thousands of emails and texts, 20 visits from the company to north Alabama and the last-minute signature of a mayor named Bubba.

The key players in the recruitment of the $600 million Google data center to Jackson County gave a behind-the-scenes look at the twists and turns the project took before settling on 500 acres at a power plant that was shutting down. The recruitment was the subject of a panel discussion at last week’s Economic Development Association of Alabama summer conference.

It was a project shrouded in secrecy. At various times, it went by the codename of “Project Zebra” and “Project Spike.” Officials involved in the recruitment had to sign nondisclosure agreements even though they didn’t know the name of the company.

In April 2014, Tennessee Valley Authority project manager Spencer Sessions took the first call and began trying to find sites that matched the criteria.

Bob Smith, project manager with the Alabama Department of Commerce, was brought in a few weeks later. He said Alabama had won a fair number of data centers the previous four years – projects that were heavy with capital investment because of the technology infrastructure, but don’t have the same number of employees as large manufacturing plants.

Site Selection magazine, an economic development trade publication, had cited Alabama’s success in the data center arena. Smith said officials recognized that the state’s incentives were more geared toward manufacturing but needed to focus on data centers.

The state passed such incentives in 2012. Alabama now had a new tool in the toolbox and waited for an opportunity to use it.

Meanwhile, TVA had a site in Jackson County certified as ready for a data center.

“We had this certified data center site right next to the community college,” said Dus Rogers, president and CEO of the Jackson County Economic Development Authority.

The only problem is Project Zebra (or was it Project Spike by this time?) didn’t care for that site and wanted officials to think bigger and broader to come up with something unique or special.

“They kept wanting something big and outside of the box,” Sessions said. “They turned down multiple sites.”

Rogers and Jackson County really needed this project. TVA was in the final stages of shutting down the Widows Creek Power Plant, near Stevenson, that once employed 400 and was set to lose the last 90 jobs when the unit shut down in 2015.

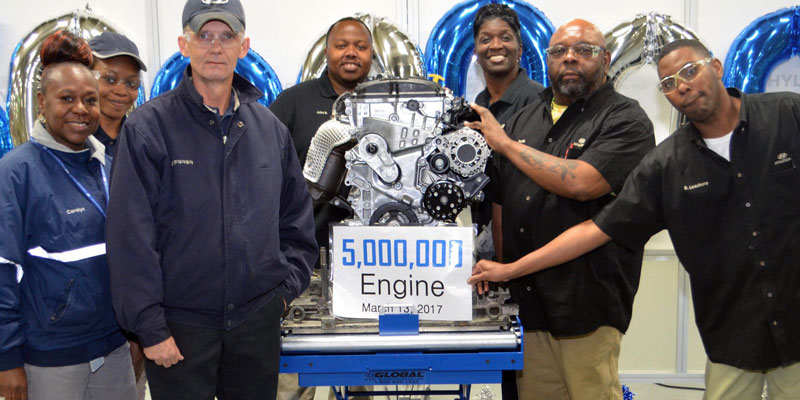

This data center project had up to 100 good-paying jobs associated with it and a capital investment of $600 million that would mean more money for schools and county services.

Meanwhile, Google was looking at 44 sites in seven states trying to find where to invest that money and create those jobs.

Google sent representatives to Alabama more than 20 times for meetings, site searches and negotiations. Sessions said most of the meetings were in Huntsville but other communities were asked to host receptions and tell the company about life in their city or county.

As Sessions and the recruitment team were trying to “think outside of the box,” the focus turned to the Widows Creek Power Plant. It was in exploring that site that TVA noted they owned an adjoining 500 acres purchased for a coal ash pond that was never built.

After much thought and planning, that site emerged as a favorite and negotiations centered on making it work.

Rogers had to personally drive the project agreement to entities throughout the county to get them to sign something that still didn’t have the name “Google” on it.

The final signature came from Bridgeport Mayor David “Bubba” Hughes.

Smith and the Department of Commerce team were applying data center incentives for the first time while ironing out the state’s project agreement.

With the agreements done, everyone tried to keep the project out of the media until the formal announcement with Gov. Robert Bentley on the site several days later.

But Rogers couldn’t help but mark the occasion.

“I took my wife to Dairy Queen for a banana split to celebrate,” he said. “Google doesn’t come along every day in northeast Alabama.”

Since the governor joined other officials to announce the project more than a year ago, months have been spent preparing the site and construction has started on Google’s data center. Two boulders were kept in place on the property and will serve as part of an entrance into what will be called the Widows Creek Technology Park.

In other states, Google has grown beyond an initial data center to add operations in a technology park setting. Jackson County, TVA and Alabama officials are hopeful Google will do more on the Bridgeport property.

For now, they are glad that Google’s last search ended up with Alabama as the top result.