A provocative New York Times op-ed last week argued that political scientists oversimplify the great divide in American politics as an argument between rural denizens and urban residents.

Actually, the author says, the country’s politics fracture 11 different ways, the result of historical and cultural differences that split the nation into 11 distinct “countries.”

Portland (Maine) Press Herald reporter Colin Woodward, who developed the theory in the 2011 book “American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America,” uses Mobile in the Times piece to bolster his argument. He lists the coastal Alabama city along with Boise, ID; Colorado Springs, CO; Knoxville, TN; Tulsa, OK, and Wichita, KS, as smaller cities that defy the conventional wisdom that cities are “reliable bastions of Democratic support.”

Woodward maintains that Mobile better reflects “Deep South,” one of his 11 nations. It encompasses parts of Texas, Arkansas, Tennessee, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina and North Carolina. He descries it as “modeled on slave states of the ancient world” and fights against federal power, taxes on the wealthy and labor and environmental regulations.

It historically has been diametrically opposed to the interests of “Yankeedom” — which covers New England and states in the supper Midwest. In “Deep South” and other culturally conservative regions, he writes, rural and urban majorities supported Republican candidates in all three [of the last national] elections, whether voters lived in central cities, wealthy suburbs, mountain hollers or the ranches of the high plains.”

Woodward’s theory holds when examining voting returns at the county level. All but 13 Alabama counties voted for President Donald Trump in 2016. In Massachusetts, the heart of “Yankeedom,” every county supported Democrat Hillary Clinton.

A more granular analysis of election results, however, suggests that urban voters in the North do not vote appreciably different than their cousins in the South or elsewhere.

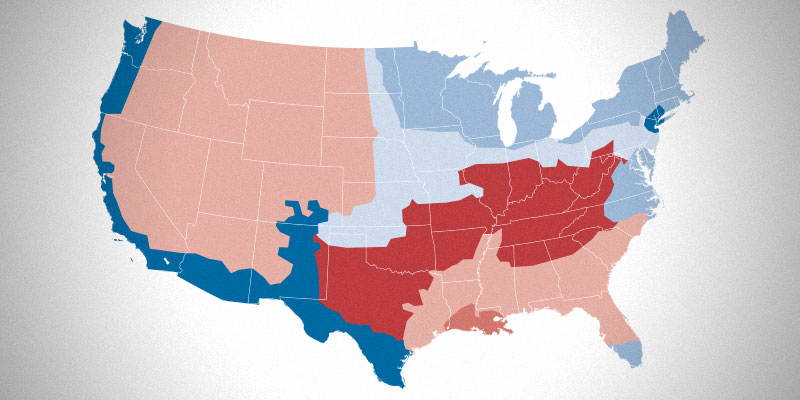

A detailed map published by the Times just a few days before the op-ed makes it easy to test the hypothesis. Trump won Mobile County, for instance. But the Times map shows the vote broken down to the precinct level. There is plenty of Democratic blue in the city, itself.

The same goes for Huntsville, where Clinton carried many of the polling places in the city but lost overall in Madison County. Tuscaloosa, Gadsden, Anniston and Dothan all show the same pattern — little pockets of blue surrounded by precincts that grow a darker shade of red the further they are from the city center.

This pattern is evident in “Yankeedom,” as well. Although Clinton swept every Massachusetts county, at the precinct level, there is plenty of red in the rural areas in the middle of the state and in the southeast outside of Plymouth.

Clinton won Rhode Island by 15.5 percentage points, one of her best states. She carried two of the state’s three counties, and the one she lost, Kent County, she lost by just 548 votes. But the precinct map shows a sea of red in Rhode Island. Clinton’s victory statewide came from dark blue precincts in Providence and a lighter shade of blue in Newport and smaller cities.

The same urban-rural divide shows up again and again across America. Wherever large numbers of people live in proximity, Clinton precincts are sure to follow — even in overwhelmingly Republican states. The most densely populated parts of Salt Lake City, as well as the smaller cities of Park City and Ogden, are blue — even as the rest of Utah mostly was red.

That is not to say that regional differences are nonexistent. While black voters behave more or less the same everywhere — exit polls suggested Clinton won 92 percent of the African-American vote in Wisconsin and 89 percent in Georgia — there is variation among white voters.

The blue in Northern cities like Philadelphia, Boston and New York extends further into the suburbs than it does in Southern cities like Atlanta, Birmingham and Nashville.

While 75 percent of white Georgians backed Trump, the president won only 53 percent of white voters in Wisconsin.

Still, the more urban the neighborhood, the more likely it is to vote Democrat — regardless of the ethnicity of its residents.

@BrendanKKirby is a senior political reporter at LifeZette and author of “Wicked Mobile.”