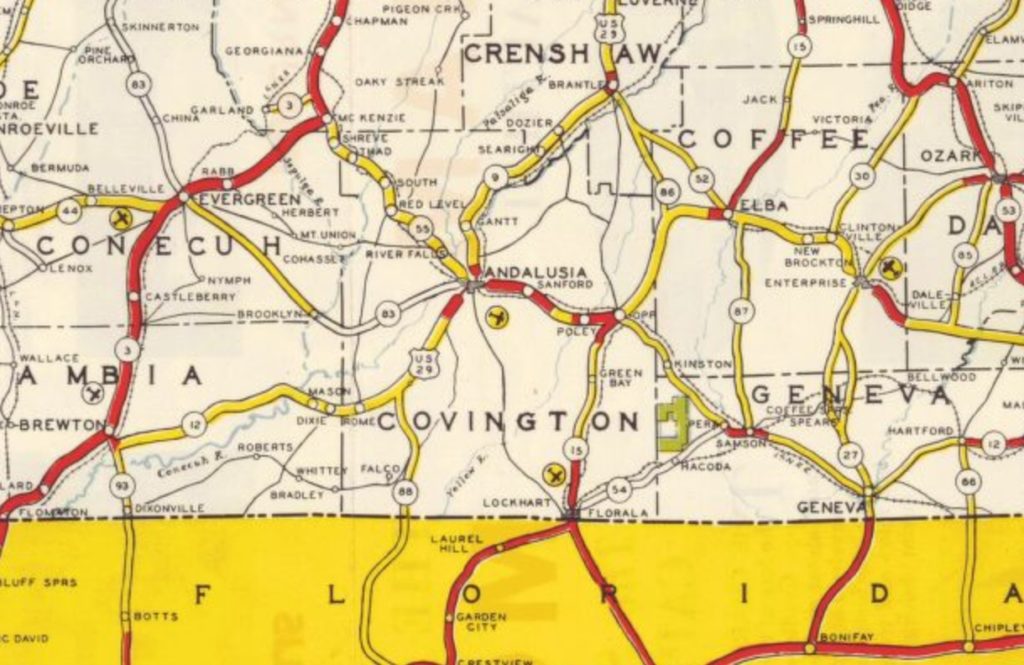

Small towns are scattered throughout South Alabama. To many, they are just blurs or brief stopping points during trips to Florida’s Gulf Coast beaches.

They come in different sizes and have funny names like Florala, Elba, Samson, Slocomb, McKenzie, Enterprise, Opp, Hartford and Brewton. They are not unlike any of Alabama’s numerous other small towns. Like many, bypass routes have been built to route traffic around their business districts. Some, like Castleberry, are notorious speed traps and have been for the last several decades.

There is one that seems a little different than the rest – the city of Andalusia.

People in nearby towns describe it as “aristocratic.” And they may be right. At first glance, it seems like a place with a little swagger to it – historic buildings that have been or are in the process of being refurbished, new schools with athletic facilities that outshine its nearby rivals and a lively downtown that doesn’t turn into a ghost town after 5 p.m.

From his office in a city hall, a structure built in 1914, renovated in 2004 and since retrofitted with modern bells and whistles one might expect for a small-to-mid-size company, Andalusia Mayor Earl Johnson acknowledged the reputation.

“Andalusia has always been seen to be a forward-moving progressive town,” Johnson said in a sit-down interview with Yellowhammer News. “There’s something about the name ‘Andalusia’ that’s sort of sexy, cool.”

It’s a posture that isn’t unwarranted.

Earlier this month, Shaw Industries, Inc., a Dalton, Ga.-based carpet manufacturer announced a $250 million technology investment into its Andalusia facility.

A week earlier, the nearby South Alabama Regional Airport announced the new tenet Dyncorp was “immediately” bringing 45 news jobs to maintain and repair the TH-57 Naval helicopters.

Those announcements suggest a trend is underway in the south-central Alabama city of nearly 9,000 residents.

Andalusia’s ‘Renaissance’

Upon one’s first visit to Andalusia, you can’t help but notice many of the city’s historic structures. Over the years, many of those buildings fell into disrepair and began to show their age.

Rather than tear them down and turn a blind eye to Andalusia’s heritage, Johnson saw the opportunity to preserve some of those structures, and in some cases at a bargain for the local taxpayers.

“This revitalization – I call it Andalusia’s renaissance,” Johnson explained. “We have been working on [it] for 20 years now – Andalusia has been getting in place to see a Renaissance of its old self coming into place, and we’re dead in it right now. We’re on top of it.”

One of the first steps of this “Renaissance” was the city hall, a structure built in 1914 and was formerly the Three Notch School. It was renovated in 2004 by the city for $3.5 million – arguably much cheaper than what it might have been if the city had started from scratch in its quest for a new city hall.

In that same spirit of revitalizing old school properties, Johnson’s administration took what was known as the Church Street School, a building built in 1923, and renovate it to become the Church Street Cultural Arts Center, home to the Andalusia Ballet.

Like many of the small towns throughout the South, the heart of Andalusia is the town square. It is bordered by the Covington County Courthouse to the north and various shops and office buildings on its other three sides.

The city’s most memorable and iconic structure is the First National Bank Building, also referred to as the Timmerman Building, at the southeastern corner of the city’s square.

The six-story high-rise building was built in 1920 and has had a mixed history of occupancy in its nearly 100 years of existence. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. The city acquired the building in early 2017 for $260,000 plus $1,500 in closing costs.

Johnson explained how the city acquired the building from its previous owner in California and got half the purchase price donated from a charitable foundation.

“I knew the guy owed some money on it, and I knew the note was coming due at a certain time,” he explained. “I said if we were going to be able to get this, now was going to be the time. I started quietly negotiating about buying the building from him.”

Currently, the building’s ground floor is occupied by Wiregrass-based Milky Moos Homemade Ice Cream, a deal the city inked earlier this year. Johnson said he foresaw the remaining levels to be a mix of commercial and residential.

Another building featured in the city’s downtown portfolio, and one that about which Johnson speaks very enthusiastically is its historic theater. A lawyer by trade, Johnson was able to use his knowledge of the tax code to engineer a deal for the city’s acquisition of the theater through a donation of the property.

Under the previous owner, the theater building was deteriorating. However, once taking ownership of the building, the City of Andalusia put $1.4 million toward renovation, to make way for Clark Theaters and is now equipped with all the modern amenities one might expect for a movie-going experience.

Johnson isn’t shy about his city’s role in creating venues for private enterprise. He pledged his support for free enterprise but argued in some cases government has a role in improving the quality of life and opportunity for its constituents.

“I believe in the free market,” Johnson explained. “I believe in capitalism. I believe in the free-market system. But some people worship it. They think it has all the answers to all problems. No, it doesn’t. It doesn’t always fix everything. Any manmade system is not perfect, and small rural towns – sometimes it doesn’t work. You’ve got to do something else to make it work. And the things that I’m talking to you and told you about are perfect examples.”

Among the other properties that have undergone rehabilitation were former Andalusia Mayor John G. Sherf’s Springdale Estate, the old AlaTex headquarters, now the home of the Andalusia Area Chamber of Commerce, and the former downtown Andala Building, which is adjacent to the First National Bank Building and is the home of Big Mike’s, an upscale steakhouse.

Evolution from agrarian to industrial and overcoming globalization

Like many of the small towns of the region, post-Civil War Andalusia relied mostly on agriculture and timber to fuel its local economy. That would change after the turn of the century.

In South Alabama, cotton was plentiful, and labor was relatively cheaper than the national average and free from any entanglements of labor unions. Disruptions in domestic labor markets and that proximity to cotton enticed textile manufacturers to move their operations to the South.

Eventually, throughout South Alabama and the Florida Panhandle, many of the local economies of the 20th century were reliant upon the success of American textiles.

Andalusia was no exception. In 1924, John G. Scherf, a German immigrant with a background in the textile industry assumed control of the local Chamber of Commerce and co-founded Andala Co., and later Alatex. Scherf would later become Andalusia’s mayor.

Those two companies manufactured products and distributed them throughout the world, including men’s dress shirts, shorts and underwear. Those products included garments for household brands like Arrow and Van Heusen.

The 1990s brought globalization, a trend that was aided by the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). With that, a lot of the textile production operations that existed in Alabama for generations moved to Latin America and the Far East.

Andalusia was also no exception to this trend, and in the mid-1990s, it lost its textile industry.

“When Alatex closed its doors, it was a huge negative economic impact to this area,” Johnson said. “And not just Andalusia. Alatex had plants in Luverne, Troy, Crestview (Fla.), Enterprise and Panama City (Fla.). And one time, they had a big warehouse operation up in Montgomery. It was a regional player as far as employment was concerned.”

“When they finally shut the doors and locked the gate, that was a bad day,” Johnson added.

Throughout the 20th century, many localities in the region were discouraged from recruiting other industries to diversify their economy. The fear was that new industry might create a competitive market for labor and force an increase in wages.

But when textiles left, some municipalities were caught flat-footed and scrambling for answers on how to fill that void.

“Basically, what I saw was people – all they wanted to do was cuss NAFTA,” Johnson said. “’If it wasn’t for NAFTA, if it wasn’t for NAFTA.’ Well you know, we can’t change that.”

From that point forward, Johnson said he saw the need for Andalusia to diversify its economy. At the time, Johnson was practicing law and serving on the board of the local airport authority. The desire to see his hometown expand its economy catapulted him into politics and eventually mayor.

Hometown utilities give workforce, economic advantages

In the 1930s during President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Rural Electrification Act (REA) was passed into law. At the time, electricity in Andalusia was sparse, and only a few places had it, which was just enough to power some lights. Under REA, the Alabama Electric Co-op (AEC) came into existence and was headquartered in Andalusia given its proximity to the Conecuh River, which could be dammed to generate hydroelectricity.

AEC generated and sold the electricity to municipal and county electric cooperatives and eventually became PowerSouth and is still headquartered in Andalusia today.

Later came the Southeast Alabama Gas District, also headquartered in Andalusia.

According to Johnson, all those were ingredients in setting the city of Andalusia apart from some of its neighbors.

“Though we were primarily agriculture, timber and textiles, we had these other things going for us that a lot of cities didn’t have,” he explained.

Johnson maintains there are more engineers in his city per capita than anywhere else in the state and that the raw number is tops anywhere outside of Alabama’s major metropolitan areas.

A unique set of problems

As much of rural Alabama struggles with maintaining quality education and health care offerings, this seems to be the least of Andalusia’s challenges.

Mayor Johnson contended his city’s public-school system is the best south of Auburn. He also pointed out there are no private schools in the entire county, which suggests residents are satisfied with the public schools.

While many places in rural Alabama struggle to keep their hospitals open and functioning, his city’s hospital Andalusia Health isn’t facing those struggles.

Instead, Johnson said Andalusia’s areas of concern are retail and housing.

On the retail front, Johnson is seeking suitors to fill the void left behind by the now mostly vacant Covington Mall. With the nearest major shopping centers in Montgomery, Dothan and Destin, Fla., Johnson insists Andalusia is a prime opportunity for a prospective retailer.

“People who are interested in the retail business, I would show them are market studies that show we have 150,000 people in our retail market,” Johnson said. “Then I would take them and introduce them to about four or five retailers we have brought to Andalusia in recent years and ask that person to talk to this prospect and tell them what working with the City of Andalusia is like. And I will guarantee you they will tell you it’s the best experience they ever had working with a government. Andalusia is the best experience they ever had as far as getting things done, business taken care of, and cutting the expense and costs of getting their business in business as quickly as possible.”

“The market we have and the reputation and experience we have understanding their problems and making their job easier,” he added.

Housing in the City of Andalusia is relatively affordable. With a median home price of $125,000, Andalusia is slightly lower than the state’s median price at $129,000. However, there is a lack of apartment housing in the city.

“Our other big challenge is housing, apartments – and we’re working real hard on that,” the Andalusia mayor said.

Johnson said he anticipates that problem to be self-correcting.

“More housing in the way of upper-level apartments and also single-family dwellings,” he said. “All that’s starting to show up now, and that’s coming.”

Geographic location, airport highlight city’s transportation offerings

Given the city’s unique location, an hour and a half drive from Montgomery, Dothan and the Florida coastline and two hours from Mobile, Johnson has a wish list of road and highway projects but knows his city isn’t a priority.

Currently, the city is connected to Interstate 65 by four-laned Alabama Highway 55 headed north and to Dothan by a four-lane U.S. Highway 84 headed east. Ideally, Johnson says he would like to see U.S. Highway 331, which passes through nearby Opp, four-laned to the beach and U.S. Highway 84 four-laned westbound to the Alabama-Mississippi state line.

However, the most significant transportation asset for the city may not be its highway connectivity, but instead, it’s an airport.

Johnson, who launched his career in politics from his position on the board of the local airport, touts the South Alabama Regional Airport as one of the many jewels in his city’s crown.

The airport touts a 6,000-foot by 100-foot instrument equipped runway and can support most types of military and general aviation aircraft.

Johnson tells of the airport’s evolution from his early involvement to now — which includes 50 hangars, two of which are large enough to house the military’s C-130s and are now a center of operations contractor Yulista.

The airport also has a unique capability that allows for hot refueling of military aircraft, including airplanes and helicopters. Aircraft can refuel at Andalusia’s airport without having to shut down, and therefore avoid wear and tear on engines.

Johnson notes the airport’s proximity to Ft. Rucker to the east and Eglin Air Force Base and Pensacola Naval Air Station to the south, which makes it a favorite refueling spot.

The closing argument: Come to Andalusia for quality of life, lower cost of living

After spending more than four hours with Mayor Johnson, I asked him to offer a closing argument to those who might consider Andalusia as a location for a home or a business.

His answer: quality of life for a bargain.

“Our quality of life in Andalusia – I don’t think you can beat it, and here’s the reason why: We have a lot of things in Andalusia you won’t find necessarily in the Birminghams of the world,” he said. “We have schools that are among the top schools in the state. To get that in Montgomery, you’re going to have to pay about $15,000 a year in tuition to somebody per child. Health care, top-notch. No, we don’t have a university hospital here. We don’t have many of the specialists, but you’re still within just a short drive of that.”

Johnson plugged his city’s “active faith community” and its people as another aspect of his closing argument.

“I know people say every you go ‘we got great people,’ but we really do,” he continued. “And as far as looking for something to do, if you want to be involved, you can get involved to the level you want to be involved and make a difference in the community in a town like this.”

All this comes, he adds, at a much lower cost than Alabama’s bigger cities.

“You can live in Andalusia at a level that would cost you probably 30-to-40 percent more in one of the metro areas,” Johnson added.

@Jeff_Poor is a graduate of Auburn University and is the editor of Breitbart TV.