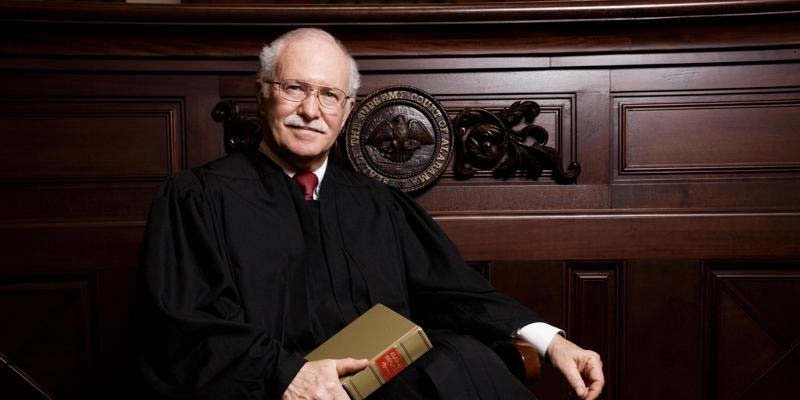

Former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore’s career may have ended in December when he lost a special election for the Senate, but his shadow lives on in the state’s Republican politics.

Tuesday’s GOP primary showed that when Moore’s longtime protégé, Justice Tom Parker, took down incumbent Chief Justice Lyn Stuart.

Parker openly embraces his Christian faith and talks about how it informs his view of the law and the Constitution. He ran ads during this campaign attacking progressive power broker George Soros and the Southern Poverty Law Center, which filed an ethics complaint against him. Earlier this year, he won a free speech victory in federal court when a judge upheld his right to speak out publicly on legal and political issues.

Rick Shaftan, who served as a consultant Parker’s campaign, said he sees some parallels to past Moore campaigns — but only up to a point.

“The two races were totally separate,” he said. “They were just different.”

Parker’s victory over Stuart was narrow — he won by about 4 percentage points — but was widespread. He carried most of the state’s counties and out-performed her in every region of the state except for her home base in southwest Alabama. Stuart, who once served as a circuit judge in Baldwin County, won there and in the surrounding counties in the Mobile area.

Despite having served as statewide officer for nearly two decades, however, Stuart found little success anywhere else.

That includes urban counties with higher numbers of educated and upper-income voters who often favor candidates like Stuart, who won the backing of the state’s business interests.

In the familiar Alabama Republican divide, the path to victory for an economic conservative running against a social conservative is to run up the score in urban and suburban precincts and then hold off her opponent in the rural counties.

Stuart did not do nearly well enough in the places that she needed to, however. Although she won Mobile and Montgomery counties, she lost Madison, Lee and Tuscaloosa counties. And while she won Shelby County and was winning in Jefferson County, the margins were too close — less than 3 points in Shelby and about 8 points in Jefferson — for her to withstand Parker’s strength in rural Alabama.

Shaftan said the Parker campaign spent relatively little in the Mobile market, figuring Stuart would run strongly there, and instead spent limited resources elsewhere.

Shaftan said the Stuart campaign, particularly earlier in the campaign when Parker was not on the air, did a good job of converting her favorability ratings into votes in surveys.

“Her ads were definitely good. It showed up in our polling,” he said. “Her problem was she didn’t have a lot to say. And when you don’t have a lot to say, you can’t run a three-week campaign.”

With less campaign money, meanwhile, Parker, did not begin airing ads on broadcast TV stations until Friday. Shaftan credited that late burst of advertising with helping Parker close a deficit that internal polling had indicated was about 10 points.

In some ways, the chief justice race was like Parker’s 2004 campaign for the state Supreme Court. Then, as now, he faced a female incumbent who had strong backing from business interests. Parker barely knocked off Justice Jean Brown in the primary, winning 51 percent to 49 percent.

Shaftan recalled Parker winning 59 of 66 counties in 2004, but he lost by big margins in the big-population counties and lost nearly every county seat. Tuesday’s victory of Stuart was broader.

“We had a stronger message. People are looking for conservative judges,” he said.

Shaftan said it is also is clear that a message of confronting bullying tactics of the Southern Poverty Law Center resonates more widely among Republican voters than just those animated by social issues.

“It has a lot more appeal in the suburbs than people might realize,” he said.

With Stuart’s loss, two previous Moore stints that ended early due to ethics investigations and Democrat Sue Bell Cobb’s resignation during her first term, it now has been 23 years since a chief justice in Alabama completed a six-year term.

Parker will attempt to break that cycle, but first he must overcome Democrat Robert Vance in November. Shaftan previewed a campaign that will depict the former Jefferson County circuit judge as a “liberal judge.” He said he expects Democrats to spend heavily on the race.

“It’s not going to work,” he predicted.

Updated at 9:52 p.m. to correct an error in Rich Shaftan’s title.

@BrendanKKirby is a senior political reporter at LifeZette and author of “Wicked Mobile.”