Corruption at the highest level of all three branches of Alabama’s government is not just making national news, it’s making international news. Unfortunately, the latest episodes of corruption are just additional examples of the deep-seated problem of corruption in Alabama. One can only imagine what this corruption is costing the state in terms of economic growth and development. Expanding and maintaining public accountability and transparency is necessary to curb Alabama’s culture of corruption and to help promote economic prosperity in Alabama.

Corruption in Alabama politics not only makes Alabama less attractive for business investment—meaning, less job growth and opportunity—actual corruption costs each resident in nine of the ten most corrupt states, including Alabama, an estimated average of $1,308 per year. Even just the perception of corruption causes real damage to the business environment in Alabama by discouraging investment. That is a problem worth solving.

Alabama is frequently listed as one of the most corrupt states in the country by the Harvard University Center for Ethics. A separate state-level corruption study recently published in Public Administration Review also listed Alabama as one of the most corrupt states in the nation. In our recently released study, Alabama at the Crossroads: An Economic Guide to a Fiscally Sustainable Future, my colleague John Dove and I find that tackling corruption in Alabama is necessary to put Alabama on the path to a fiscally sustainable future.

Ensuring Alabamians–and future Alabamians–that they can hold public officials accountable is one way to reduce both real and perceived corruption. That means public accountability across the board, including for our state pension system that is facing an $80 billion funding gap due to flawed accounting practices which substantially understate pension liabilities, putting our fiscal future in jeopardy.

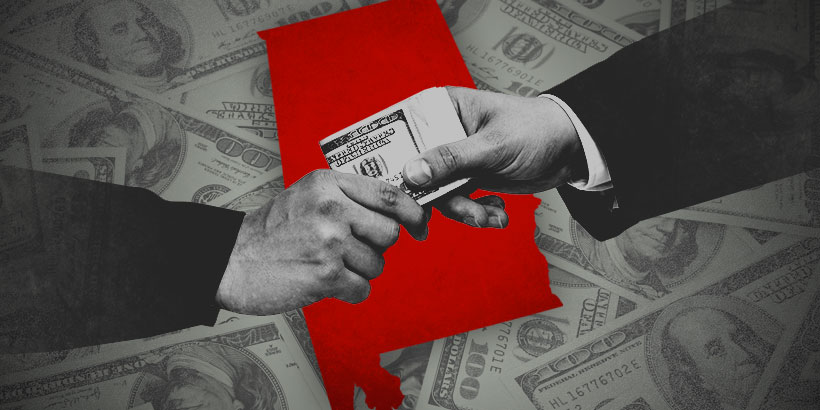

The lack of transparency contributes to the state’s corruption problems especially when it comes to public access to information, political financing, and redistricting. Reducing political corruption in Alabama, both real and perceived, will require expanding and maintaining accountability and transparency in all areas of state regulation, spending, and employment. It also means fostering a principled political culture that rejects corruption, with informed voters holding policymakers accountable.

Perhaps even more troubling than the cost of corruption in Alabama, is the impact of corruption on business and job growth. A World Bank study found that corruption has a more harmful effect on business growth than even taxation. When corrupt public officials direct tax money toward sectors conducive to bribery, such as highways and construction, or for other self–serving functions like wage and salary increases, they create an unfair political and economic environment on the backs of taxpayers. In another study looking at corruption in just the U.S., the economists David Mitchell and Noel Campbell found that concentrating resources on reducing corruption at the state level is more effective in producing business growth than economic incentives programs.

The State Integrity Investigation Report Card finds that Alabama is particularly vulnerable to corruption when it comes to public access to information, legislative accountability, state pension fund management, political financing, and redistricting.

State leaders serious about weeding corruption out of Alabama politics—and saving taxpayers more of their hard-earned money—should take these reports seriously and implement basic procedures to add more accountability and transparency to our political system. Accountability and transparency will reduce both real and perceived corruption.

Taking steps to tackle political corruption in Alabama, by expanding public accountability and transparency, will improve investment and job growth and help cut wasteful expenditures. We can do this by strengthening our information access laws and procedures, being more transparent and open about redistricting, and making and enforcing stricter conflict of interest laws for public officials.

Daniel J. Smith is the associate director of the Johnson Center at Troy University. Follow him on Twitter: @smithdanj1