It has been a whirlwind few weeks in the race to become Alabama’s next U.S. representative from the 6th Congressional District.

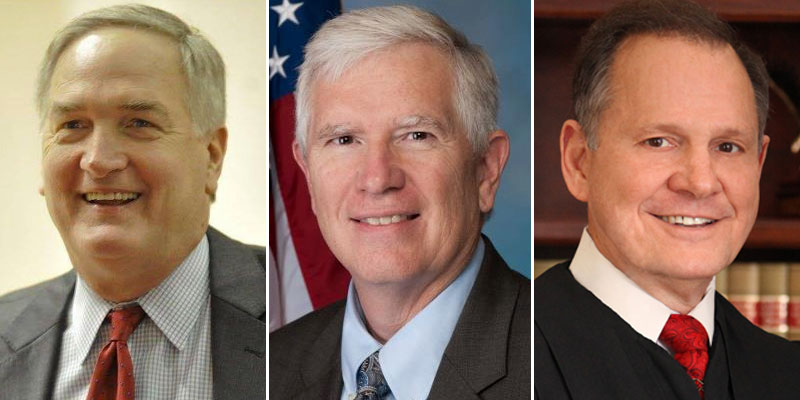

Paul DeMarco won 33 percent of the vote in the crowded Republican primary, giving him a commanding lead going into the runoff against Gary Palmer, who came in second in the primary with 19 percent. Not only did DeMarco receive by far the highest percentage of the vote, he was also the top second choice of most voters who cast a ballot for someone else, according to third-party polling.

It appeared that DeMarco was well on his way to being elected to Congress, as long as he ran a relatively error-free campaign. And there was every reason to believe he would. During the primary, while several of the other candidates sniped at each other, DeMarco seemed to mostly stay out of the fray.

Here’s a great example:

Chad Mathis was pummeling DeMarco, Palmer and two other Republican primary contestants, Scott Beason and Will Brooke, with negative ads dubbing them “the gang of four,” a group of liberal politicians who had committed egregious “sins against conservatism.”

In the final days of the primary, Beason, Brooke and Palmer came together and held a joint press conference condemning Mathis’ attacks, a surprising move for campaign rivals so close to election day. DeMarco chose not to participate.

It was a smart move.

He was slowly building a case for the inevitability of his election by setting himself apart.

I’m told that George Wallace used to say that he’d rather someone tell him they thought he was going to win than that they were planning to vote for him. People want to support a winner, he believed, so the most important thing he could do was convince people he was going to win.

Coming out of the primary, DeMarco sure looked like a winner.

But things changed dramatically once Palmer got DeMarco one-on-one.

It started with the debate at Regions Field. DeMarco struggled, but it was a relatively minor speed bump when put into the context of the entire race. Debates do not win elections, and in spite of his lackluster performance, DeMarco had avoided making any gaffes that would get replayed over and over again and sink his candidacy.

The campaign should have carried on as it had before, perpetuating the narrative of inevitability. But it didn’t. They panicked and ran an attack ad on Palmer that was widely criticized as inaccurate and has now dominated the last three weeks of conversation surround the race. DeMarco followed that up with a brutal appearance on the Matt Murphy Show. I’m glossing over all the details here, but in short, I honestly cannot recall a campaign having a worse few weeks than DeMarco has since June 15th.

But then I realized something: my gut still said DeMarco was going to win. I’ve changed my thinking a little and now believe the race is a tossup — a 50-50 shot for either candidate. But even though Palmer seems to have all the momentum, there’s one distinct tactical advantage that DeMarco has over Palmer that could be the difference in the race, and you’re probably not going to like it.

Let’s take a quick look at a couple of the television ads that have been run by both campaigns.

First, Paul DeMarco.

He’s worked hard to present himself in ads as a fighter, someone who is, in his words, “a conservative that will stand up for what we believe, no matter what.”

This ad, titled “Defender,” pretty much sums it up:

I count five different DeMarco ads that essentially had that same message and tone.

But he’s also blistered Palmer with attacks, both on TV and through direct mail.

And in DeMarco’s latest ad, he doubles down on his accusation that Palmer would raise taxes, a stinging criticism in any Republican primary. I can’t find an embeddable video of the ad (I’ll update if I do), but here’s the transcript:

Gary Palmer says he never supported a tax increase. Oh really? That isn’t true.

Palmer suggested raising your property taxes, and, like Obama, believes higher incomes should be taxed more.

Conservative RedState.com called his views on taxes ‘Obama-like.’

And on immigration, Palmer was critical of Alabama’s tough anti-amnesty laws.

See for yourself at GaryFacts.com.

Gary Palmer: Not telling the truth on taxes, wrong on immigration.

As the ad mentioned, the DeMarco campaign has also launched a website entirely devoted to hammering Palmer.

Now, let’s take a quick look at Gary Palmer’s ads.

He’s fashioned himself the faith and family candidate who also happens to be a “policy guy,” and he’s focused a lot on his personal story. The two ads below are good summary of how he’s presented himself.

The closest thing to a negative ad Palmer has run is this one, titled “Misleading,” which was a response to DeMarco’s original attack.

A Washington, D.C.-based conservative group called Club for Growth did briefly go up on TV with an ad attacking DeMarco, but that was separate from the Palmer campaign. Congressional campaigns are by law not allowed to coordinate with PACs.

So here’s the deal.

I will concede that DeMarco’s negative ad is what got him into a lot of this mess in the first place. But if the last several days are any indication, if DeMarco’s going down, he’s going down swinging at Palmer. And whether you like it or not, that gives him a tactical advantage over Palmer, who seems content weathering the storm with a final push of feel-good ads.

Everyone says they’re sick and tired of “negative campaigning,” but it sure doesn’t seem that way once we go to the polls.

Why do you think 86 percent of Barack Obama’s ads during the 2012 presidential campaign were attacks?

“The answer is simple: They work. And they work very well,” said Ruthann Weaver Lariscy, a professor at the Unviersity of Georgia who has extensively studied negative ads and their impact on voters. “Our brains process information both consciously and non-consciously. When we pay attention to a message we are engaged in active message processing. When we are distracted or not paying attention we may nonetheless passively receive information. There is some evidence that negative messages may be more likely than positive ones to passively register. They ‘stick.’

“Over time, a message is likely to become disassociated from its sponsor,” Lariscy continued. “There is some evidence that negative ads benefit from this effect: Immediately upon hearing and seeing an attack, you might dismiss it as being ‘just politics.’ Then, typically several weeks later when you are making your voting decision, something in your mind recollects the negative information. You have likely forgotten when or where or from whom you heard it — but the negative content ‘stuck.’”

If Palmer still loses next Tuesday after catching all of the breaks and gaining all the momentum over the last few weeks, it will likely be because negative ads work, whether we want to admit it or not.

Follow Cliff on Twitter @Cliff_Sims