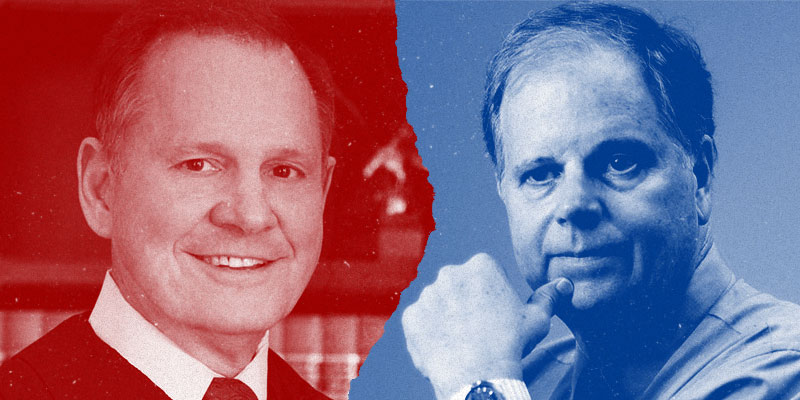

Yes, there are good reasons to believe Roy Moore misbehaved with teenage girls 40 years ago.

My previous column explained why it’s not obviously absurd for many Alabamans to disbelieve the allegations against the former chief justice. A man’s longtime public reputation does merit at least some benefit of the doubt.

On the other hand, some of the emotional, reflexive, and conspiracy-minded assertions put forth by many of Moore’s backers – not to mention absurd comparisons to Saints Mary and Joseph, or calls to criminally charge Moore’s accusers – are examples of extreme ignorance, sheer stupidity, or both.

As my earlier column handled the arguments in list fashion, let me use a parallel format here.

First, many Moore defenders say that just because the story ran in the “liberal” Washington Post, it therefore cannot be believed. This is nonsense on steroids and amphetamines at the same time. Many news outlets may have a liberal bias, but ones as prestigious as the Post also have very high professional standards, and many stages of review. Post reporters and editors may (or may not, and often don’t) have biases that subtly affect their stories, and they may make errors on details, as humans often do. But they don’t just make things up, nor do they publish things they don’t fully believe are true.

In this case, by professional journalistic standards, the original story on Moore was quite well sourced and very tightly reported. While anybody can pick nits with just about any significant news story, this one is far more likely to land in college journalism classes as a legitimate example of a story done right than of one done sloppily (or worse).

Second, the idea that this is a “last minute” smear is absurd. Publishing a story like this a full five weeks before an election is hardly a last-minute bombshell. Instead, it allows plenty of time for follow-up investigation, for Moore to defend himself, and for the voters to weigh it all accordingly. Indeed, the Post has acted with relative dispatch, publishing the story as soon as it considered the article to be airtight, rather than when it would politically do the most damage to Moore.

Third, it is fallacious to assume that these allegations cannot be true just because they didn’t surface during more than 30 years of Moore’s prior political activity. Not only do true sex abuse allegations quite often arise only decades later, even for the most public of men – see former House Speaker Dennis Hastert – but there is copious evidence, historical and psychological, with peer-reviewed studies, to the effect that real victims of such abuse often do take years and even decades to come forward.

But in this case, there are two parts to the “why didn’t it come up earlier” question. Moore’s defenders say they are suspicious of the charges not just because it took so long for the victims to speak up, but also because they think journalists or opposing campaigns surely would have dug up these charges before now due to the longtime, controversial notoriety of Moore. This might seem a reasonable premise, but it’s not. The fact is that Moore’s career did not lend itself to thorough, research-heavy vetting until now.

First, Moore hasn’t been a nominee for a federal office before. National news orgs may not have liked him, but they didn’t really care because he was Alabama’s problem. Now that he may go national, though, the Washington Post has a lot more resources to put into research than do the local papers, and the state Democratic Party for years has been so denuded that it may as well not exist. (For that matter, state newspapers began cutting way back on “investigative” work as early as about 2005.)

Moore’s trajectory as a statewide candidate did not begin until 2000, when he ran for state Supreme Court. That was the year of the hotly contested Bush-Gore race; a state court race wasn’t receiving many resources then. I think I’m right that I was the only journalist to do a major-research feature story on his race – and I focused entirely on judicial/legal background and philosophy, not on personal (non-professional) history.

Then, Moore was ejected from office in 2003 and thought to be politically dead. Then he ran a very weak primary campaign for governor in 2006. No need for anybody to expend major resources investigating him; he was no real threat to win. Then he ran another weak campaign for governor in 2010. Of four major candidates, he came in fourth. Again, no need to expend resources against him. His comeback in 2012 caught everybody by surprise. And in the general election, it was a presidential year, so nobody paid much attention, again, to Alabama’s state Supreme Court race.

Fourth, at least in the Post story (this excludes Monday’s charges from the client of drama-queen-lawyer Gloria Allred), all the descriptions of the alleged incidents, from all 30 sources – all told independently without the sources being able to compare notes with each other – were remarkably similar in their descriptions of Moore’s behavior. And for an alleged sexual deviant, Moore showed quite idiosyncratic tendencies (according to the sources). Yes, they said, he was interested in teenagers, but he did not (unlike most sex abusers) use force; he did take “no” for an answer, and he drove the girls home, almost in gentlemanly fashion, when they asked him to do so. These idiosyncrasies fit into Moore’s public persona of old-fashioned courtliness, which makes them even more believable. Yes, they make the allegations at least somewhat less serious than forcible assault (although any sexual contact with a 14-year-old, with or without physical force, is inexcusable and rightly called “assault”), but the consistency of the stories also lends credence to the idea that these were, indeed, Moore’s habits.

In courts of law, such apparent patterns of behavior are often admissible evidence for the jury to consider.

—-

In sum, then, it is perfectly logical for objective observers, at this point, to tend to believe the allegations against Moore – as long as they don’t yet say their conclusions are hard and fast. To recap, it is logical because the Post story met good journalistic standards, because it does not have the attributes of a last-minute smear, because it is a fallacy that Moore’s background has been thoroughly vetted by press and opponents before now, and because of the commonality of the sources’ reports about the idiosyncrasies of Moore’s alleged behavior four decades ago.

As my previous column explained why there are good reasons not to assume that Moore is guilty, these considerations show why it is eminently reasonable to take the allegations very seriously indeed.

A man in his 30s should never even be alone with a girl 16 or younger (other than a relative, or with the possible exception of a man driving home a babysitter in a pinch and in tightly controlled circumstances), much less in any remotely sexual atmosphere. If the 14 year-old’s story about Moore is true, then, yes, even 38 years later, it makes him unfit for public office.

Yellowhammer Contributing Editor Quin Hillyer, of Mobile, also is a Contributing Editor for National Review Online, and is the author of Mad Jones, Heretic, a satirical literary novel published in the fall of 2017.