A pair of researchers who study government corruption by asking the folks who should know best — journalists covering politics — are back with their latest survey.

Quantifying corruption long has been an elusive goal because there is no agreed-up criteria to measure it. Some researchers have examined public corruption convictions or indictments. But comparisons from state to state are hard to make because of differing laws and contrasting levels of aggressiveness among prosecutors pursuing such cases.

And statistics on prosecutions shed no light on a softer type of corruption — conduct that is unethical but does not cross the legal line.

Michael Johnston and Oguzhan Dincer, former fellows at Harvard Law School’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, hit on the idea several years ago of measuring corruption in a different way — surveying reporters.

Dincer, director of the Institute for Corruption Studies at Illinois State University, acknowledged that the methodology he and Johnston use has its own flaws. It is subjective and susceptible to reporters’ own bias. But he said it has the advantage of taking the pulse of men and women who see the government up close.

“You’re the watchdogs,” he said in an interview on Monday. “You watch what these guys do every day. I operate on the assumption that you know this better than anyone.”

The latests survey — the fifth prepared by Johnston and Dincer — went out Monday. It asks journalists for their assessment of how common corruption is in the executive, legislative and judicial branches in the states they cover.

The survey also asks for an assessment of both illegal corruption — conduct that actually violates the law — what Dincer and Johnston term “legal corruption,” or actions that undermine the integrity of government without violating a criminal statute.

Dincer said he and Johnston plan to publish the results of all five years’ worth of data after compiling responses to the latest survey. He said he hopes to make it available before the midterm elections in November.

Dincer said he has found a great deal of overlap between the perception of journalists and the public reputation of states considered dirty — like Illinois, Louisiana and New Jersey. And, Dincer added, the results do not change dramatically from year to year.

“It’s pretty consistent,” he said. “If there’s a major corruption scandal, it might affect perceptions of a state.”

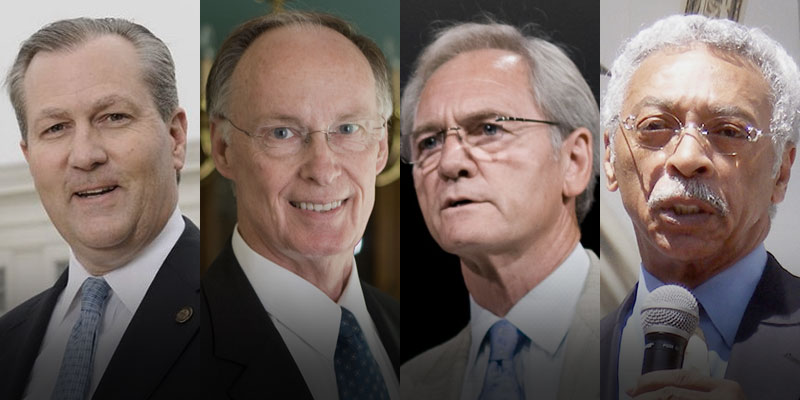

Alabama has had plenty of corruption scandals. The arrest last week of state Rep. Randy Davis (R-Daphne) was only the latest. A federal grand jury added Davis as a defendant in a case accusing former Majority Leader Mickey Hammon and Rep. Jack Williams (R-Vestavia Hills) of using their offices to try to change the law to benefit health clinics in which they had an ownership stake.

Add to that recent convictions of former Gov. Robert Bentley and former Majority Leader Mike Hubbard in unrelated cases — and convictions of two previous governors dating to the 1980s — and it is not surprising that Alabama topped the nation on the most recent corruption index.

“Alabama is consistently corrupt,” Dincer said. “It’s always there. New Jersey is always corrupt. … It’s pretty in line with what you expect to see based on news across the country.”

Dincer said he was interested in building the index because he was curious about how states other than the obvious ones would come out. He said he believes the ratings are accurate for most states. The exception, he said, might be smaller states that have relatively few journalists covering state government.

“If you have only one or two journalists respond, and they are very skeptical, it could make the state appear more corrupt,” he said.

@BrendanKKirby is a senior political reporter at LifeZette and author of “Wicked Mobile.”