A little known, counter-intuitive communication phenomenon called “the sleeper effect” means that outright lies can become more persuasive over time even when they come from a source who isn’t credible, according to decades of academic research.

Under the right conditions, researchers say the effect can make shaky stories even more believable than trustworthy ones, particularly if the message is shocking enough to have a strong initial impact on a person’s attitude and the source isn’t revealed until after the message is delivered.

So imagine hearing something that makes a strong impact on you … only to learn the source is someone you don’t find credible or whose intentions may be tainted. The sleeper effect means that as time passes, you may be likely to become more, not less, persuaded by what you heard, regardless of your feelings about the source.

The sleeper effect was first scientifically observed in 1949 when American soldiers became more persuaded by WWII propaganda films as time passed. Today, the effect is informally observed in some of our culture’s long-standing urban legends.

School-children were the first to spread the myths that Pop Rocks candy is deadly when paired with Coke, Bubble Yum gum contains spider eggs and McDonald’s hamburgers are made out of ground worms.

These myths were once so prevalent that the companies had to issue widespread public reassurances that their foods were safe.

When a prankster circulated the presidential IQ hoax in 2000, it was widely accepted that President George W. Bush had the lowest IQ in presidential history with President Bill Clinton topping the list as the smartest.

An entire website, Snopes.com, is dedicated to debunking hundreds of lies and rumors that catch fire through word-of-mouth, email forwards and social media.

It also helps explain why negative political tactics can be so effective and so dangerous. Voters can end up accepting rumors even when they suspect the source’s intentions and credibility.

It’s not surprising that political candidates fear this public tendency to believe bunk — bunk that can sometimes sink a campaign.

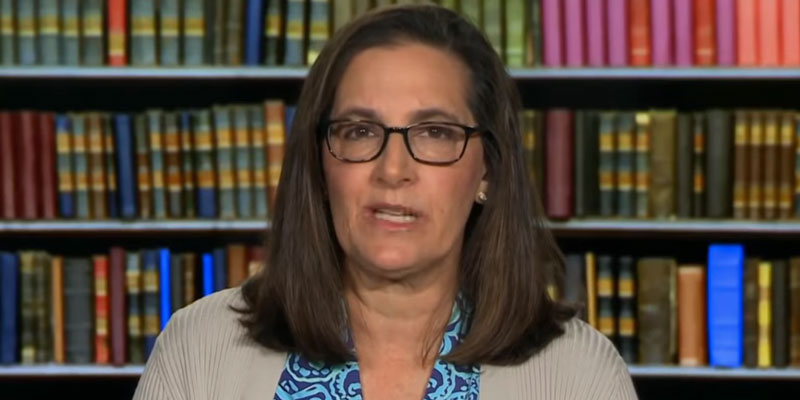

Rachel Blackmon Bryars has a master’s degree in communication with a political focus from The Johns Hopkins University