The Alabama Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries (WFF) Division’s Law Enforcement Section K-9 Unit has integrated the latest technology in its quest to track down poachers and those attempting to flee from law enforcement as well as missing persons.

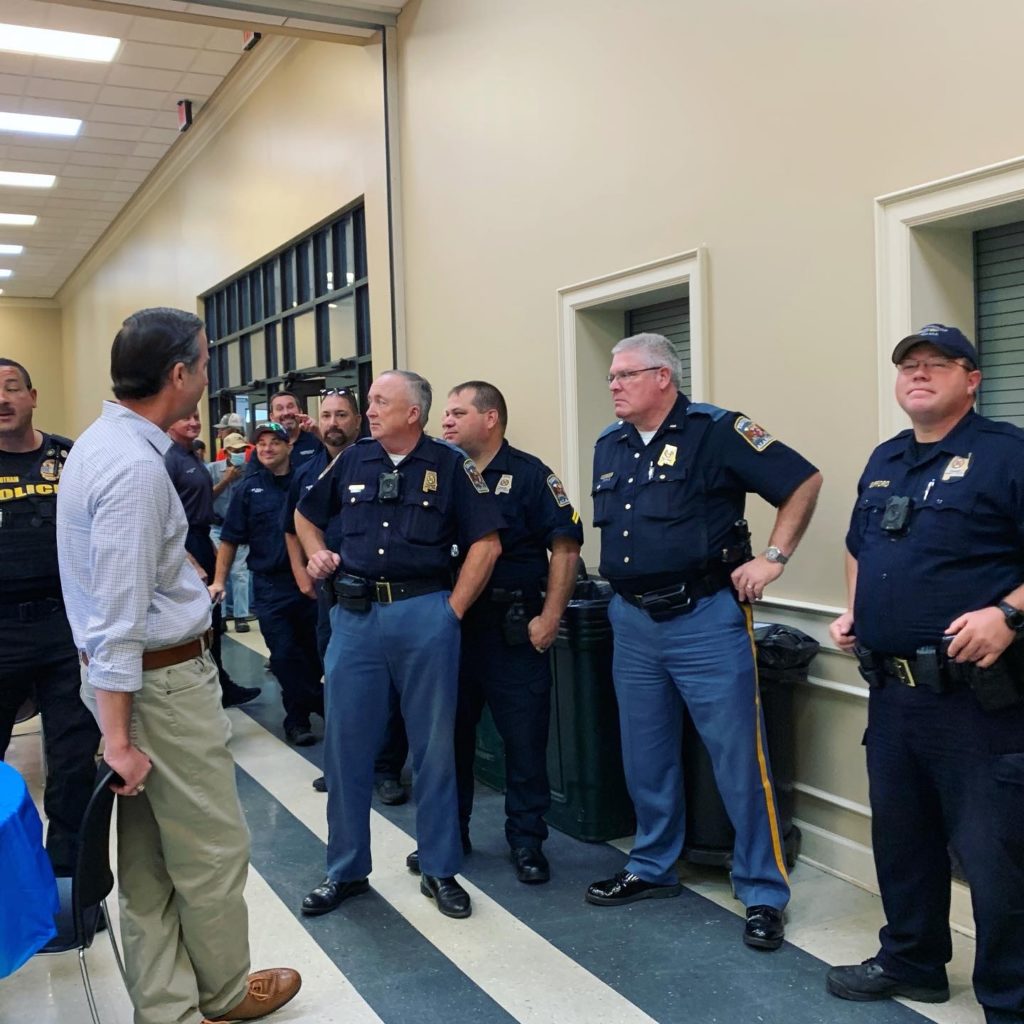

In a training session held recently in Baldwin County, the WFF K-9 unit and other WFF Conservation Enforcement Officers (CEOs) demonstrated the use of a tracking system to the Baldwin County Sheriff’s Department and law enforcement officers from several municipalities in the county.

The technology involves GPS tracking collars for the beagles used by the K9 Unit as well as a tracking unit that is on board the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency (ALEA) helicopter. When a search is in progress, each tracking unit, worn by K-9s in the form of a collar, is displayed on a screen in the portable command center, CEO vehicles and the helicopter to maximize search efficiency.

The WFF K-9 Unit was created in 2019 after CEO Brad Gavins became interested in the Alabama Department of Corrections’ (DOC) use of tracking dogs to find escaped prisoners. Corrections gave WFF one of their dogs to try and soon the K-9 unit came into existence. WFF now has eight tracking beagles deployed with Conservation Enforcement Officers around the state.

CEOs Jason McHenry of Autauga County and Ben Kiser of Calhoun County are among the officers with tracking beagles, and they were among the WFF staff at the recent training session.

McHenry explained the practical rural canine training that occurred at Perdido River Wildlife Management Area.

“We have a mock scenario set up where an individual, the suspect, is in the woods,” McHenry said. “The initial officer on the scene has made a traffic stop. That individual has fled into the woods. That officer has contacted his supervisor and asked for backup, which includes DOC, ALEA Aviation and Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries to assist in establishing a perimeter and tracking.”

McHenry said when the supervisor arrives at the scene, that individual sets up the incident command, which is the hub of communications. Responding officers check in at incident command to keep track of the officers in the field and issue assignments at the scene.

Hitching a ride with McHenry and Kiser, we loaded into McHenry’s vehicle equipped with the Garmin DriveTrack tracking receiver and rode the perimeter as the WFF K-9 Unit unloaded their tracking dogs to pick up the scent at the site where the suspect entered the woods.

During the exercise, McHenry and Kiser were able to watch the screen and see the positions of the dogs and the ALEA helicopter as they performed the search for the suspect. This allowed the WFF CEOs to move their vehicle and personnel into a position to best intercept the suspect.

Gavins, the CEO in Crenshaw County, is the team leader for the WFF K-9 unit, which procures all the beagles, man-tracking dogs from DOC already trained. The beagles are trained not to bark so the suspect won’t be alerted to the tracking team’s approach.

Gavins said the WFF K-9 Unit assists local law enforcement agencies on manhunts, and the recent training was the result of discussions on how to best coordinate their efforts and increase the chances of apprehending suspects or finding the missing persons as quickly as possible.

“We’ve had discussions on what goes right and what goes wrong during a manhunt,” Gavins said. “We talked about what we can do to get the information out to the agencies that will be on scene, setting up the search and communicating more efficiently so that we have a safer, more effective search. When the Garmin DriveTrack became available to our agency about a year ago, it worked out so well that our Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries officers became perimeter security for many searches across the state. Since we can see where the canines are in real time on a satellite image map, it becomes possible to direct officers to the area that a suspect may be fleeing through or to an area where a lost child or person suffering from dementia or Alzheimer’s disease may be located. We can see all the roads, food plots and terrain features. If the canines start to get close to a road, our officers can shut down the road for the safety of the dogs or prepare for a fleeing fugitive.”

The WFF officers can gather information from the ALEA helicopter and DOC and relay that information to the incident command center or whatever agency is in control of the scene.

Gavins said WFF works closely with the DOC and can assist in any search effort.

“We train with them and we already have the DOC tracking collar codes programmed into our computers,” he said. “If they call and ask us to come to a certain county to assist them, we turn our computers on and we can see where their dogs are on the ground. We can immediately start assisting without having to find out where the dogs are.”

Gavins said ALEA Aviation and several county aviation units tested the system and agreed to install a tracking unit in their aircraft.

“It’s a game changer for a manhunt or a search for a missing person,” Gavins said. “Sometimes the suspect can be miles ahead of the dogs. The helicopter knows where we are and can tell us if it’s a hot track or a cold track. It actually helps them get in the area where the person is running, and it keeps them in the area where the person is. With this tactic, the suspect’s focus remains on the aviation assets. It helps suppress the suspect’s movement as long as the aircraft is there. Through interviews with suspects after they have been apprehended, it became evident that if the helicopter makes a loop or is gone to refuel, that’s when a fugitive will try to cross a road or make a move. In the suspect’s mind, if the aviation is in the area, they know where they are, which keeps their attention on the aviation instead of the other efforts with the tracking dogs and pursuing officers.”

Gavins said once word spread of how successful the new technology was for performing searches, other law enforcement agencies became interested. The WFF K-9 Unit started working to develop a training course that would bring the outside enforcement agencies into the group. The training that was developed includes a morning of classroom discussion, followed by an afternoon of demonstrating the tracking system with WFF K-9s, WFF officers and the ALEA helicopter.

Gavins said the classroom discussion includes communications, incident command preparation and tracking site contamination mitigation techniques.

“When we developed the classroom portion and practical portion, one thing that was important was to clearly establish the call-out protocol for ALEA Aviation, DOC and Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries,” he said. “What ALEA Aviation stressed was that any enforcement agency that needed their help for a manhunt or finding a missing person should call right away instead of waiting eight or nine hours. ALEA’s concern was found to be the same concern that all agencies involved in this training expressed. We talk about protocols that need to be followed for a missing person or suspect – things that need to be done before calling aviation or the K-9 unit. This falls into the hands of the first responding law enforcement officer on scene. The key is to set that up right away and not contaminate the area for the canines.”

David Rainer is an award-winning writer who has covered Alabama’s great outdoors for 25 years. The former outdoors editor at the Mobile Press-Register, he writes for Outdoor Alabama, the website of the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.