For over fourteen months now, the state government of Alabama has been under a dark cloud of suspicion and accusations stemming from the indictment of House Speaker Mike Hubbard on 23 counts of felony public corruption.

The Attorney General’s office says Mike Hubbard — once the Alabama Republican Party’s fastest rising star — could not choose between power and money, so he chose to use the former to attain the latter.

Unflattering emails released by the prosecution revealed that Hubbard, a broadcast media executive by trade, was being paid upwards of $30,000 a month by various companies in other industries — at least some of which had issues before the Legislature — to be a consultant. He is also accused of having voted in favor of a measure that could have benefited one of his clients to the tune of millions of dollars, among other things.

After being indicted, Hubbard unleashed an all-out assault on the credibility of the Alabama attorney general’s office.

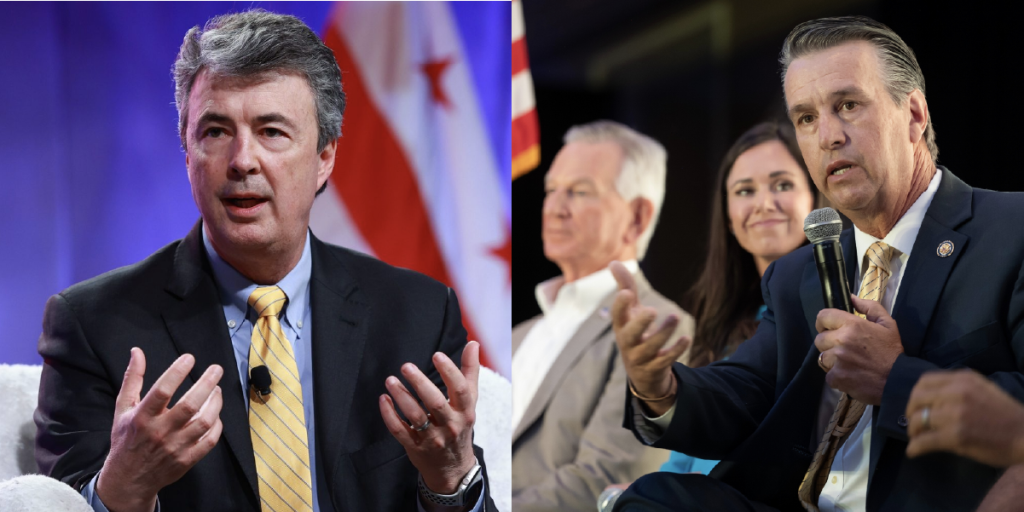

According to court documents, Attorney General Luther Strange recused himself from Hubbard’s case when the investigation began in January of 2013. He appointed longtime attorney Van Davis to serve as acting attorney general, and Matt Hart, chief of the AG’s special prosecutions unit, took the reins as the lead prosecutor.

Hart came into the job with a reputation for being a bulldog, a trait that could serve him well as he took on public corruption. But according to Hubbard’s defense team, and even some inside the AG’s office, Hart had also become known as a man who was willing to operate in the grey, a dangerous trait for someone whose job is to uphold the law — to seek truth wherever it takes him.

Former deputy state attorney general Henry “Sonny” Reagan wrote to Attorney General Strange warning him about Hart’s tactics, and even filed an internal complaint against him for “harassment, threats of physical violence, and prosecutorial misconduct.” Hart dismissed the accusations and shot back that Reagan was interfering with his investigation. Reagan ultimately resigned after 16 years on the job, but not before making accusations that support what the Hubbard defense team has been saying all along: the prosecution is inappropriately leaking information.

“I know that two high level officials in your Investigations Division believe that Mr. Hart has leaked Grand Jury information to the press and have notified you of the same,” Reagan wrote to Strange.

Throughout the Grand Jury process and even since the Hubbard indictment, sealed information has seemed to routinely pop up on pro-prosecution blogs and editorial pages.

HISTORY OF LEAKS

Six months before Hubbard was indicted, Hart went after State Representative Barry Moore (R-Enterprise).

While testifying before the Hubbard Grand Jury, Moore was asked to recall the details of a conversation he had with his soon-to-be primary opponent Josh Pipkin approximately seven months before. Unbeknownst to Moore, Pipkin had recorded the conversation, and prosecutors argued he was not sufficiently accurate in his recollection of the call during his testimony.

The indictment, which was attained using out-of-context clips of phone conversations and proved to be a stretch after Moore was found not guilty on all charges, raised eyebrows in the legal community. But throughout the entire trial, apparent leaks appeared on a pro-prosecution blog that seemed engineered to hurt Moore politically in his re-election bid.

In spite of Grand Jury secrecy laws, an article in the Enterprise Ledger noted that Moore’s opponent, Josh Pipkin, claimed “he received permission from the attorney general’s office to publicly address the issue (Grand Jury proceedings) at the Coffee County Republican Club.”

In a later Facebook post by Pipkin’s wife that was reposted by Pipkin’s campaign Facebook page, she said her husband “would love to comment now but he can’t because of Grand Jury Secrecy Laws.” But in the very next sentence she appeared to inadvertently reveal that secrecy laws were broken by saying “the AG played the conversation for you,” referencing something that could only be known by people inside the Grand Jury.

The Pipkin campaign later removed the posts, but the entire ordeal was so over-the-top a juror is said to have quipped during deliberations, “If Pipkin and (his sidekick) Tullos are going home to their families tonight after what they did, then Barry Moore should definitely be going home to his family.”

Moore, of course, was acquitted, but the leaks seemed to continue.

CAUGHT IN THE ACT

A few weeks ago Hart finally got caught with his hand in the proverbial cookie jar.

Speaker Hubbard’s lead defense firm, White Arnold and Dowd, submitted a motion to the judge to withdraw from the case. The firm has declined to disclose its reasoning, but while the withdrawal filing was made public, their actual motion was kept under seal by the judge because it referenced Grand Jury proceedings.

However, the moment the filing hit Hart’s email inbox, he forwarded it to a pro-prosecution blog, which published the sealed document.

“It did not appear to be sealed when I first viewed it quickly in the car on my iPad,” Hart explained to Alabama sports website and liberal political blog al.com. “Because we have agreed to send various media entities motions when they are filed, and because I’d received specific requests to do so in the last couple of days, I forwarded this motion to a journalist.

“As I was preparing to send it to the second person on our list, I noticed that the motion was marked ‘under seal.’”

Even if Hart’s tortured explanation is accurate in this particular instance, it is hard to ignore that his first inclination upon receiving any information about the case was to send it along to the very blog with whom the Hubbard defense team has accused the prosecution of repeatedly working in concert.

THE PLOT THICKENS

Baron Coleman, a Montgomery attorney who also works as a political consultant and hosts a local radio program, said in a sworn affidavit this week that he “used information from Matt Hart to create a ‘whisper campaign’” against Hubbard.

“At one point, Matt Hart told me in January 2014 it was a good thing for him and his office that I was in the political world ‘wheeling and dealing’ and doing political things,” Coleman writes in the affidavit.

Among those “political things” Coleman was engaged in was consulting for the campaign of Sandy Toomer, who was running against Hubbard in his Auburn-area legislative district.

Additionally, he was also a consultant for Josh Pipkin, who was running against Rep. Barry Moore.

And suddenly things really begin to come into focus.

Coleman’s breathtaking affidavit — written by a man who has been anything but an ally of House Speaker Mike Hubbard in recent years — depicts Matt Hart as a man who does not hesitate to use leaks and intimidation tactics to his advantage whenever he sees fit; in other words, exactly the man Hubbard’s legal defense team has been describing for over a year now.

But according to Coleman’s affidavit, Hart also tried to use those tactics on him.

Through a sequence of events, Hart became concerned that Coleman had inadvertently exposed him as the leak in the Grand Jury proceedings.

“When Mr. Hart became aware of this information, he called and advised me to never let that happen again,” said Coleman. “Mr. Hart threatened to put me in front of the Grand Jury, which he claimed would be ‘somewhat painful’ for him and ‘painful’ for me. Near the end of this conversation, Hart awkwardly interrogated me for several minutes about whether I had ever recorded him in any manner, including during phone conversations or face-to-face conversations… I concluded he feared I had recorded him and the recordings would be subpoenaed to show Grand Jury leaks.

“Based on comments made to me by Mr. Hart, I am concerned about Mr. Hart and the power he possesses,” Coleman concluded. “I believe his threats of a painful Grand Jury experience were designed to keep the line of communication open between us, knowing that I would use the information he provided me but would be fearful to ever reveal its source.”

CLIMATE OF FEAR

The Grand Jury process is secret for good reason. If the proceedings were public, it could discourage witnesses from coming forward or keep them from being entirely forthcoming. Additionally, if the Grand Jury declines to issue charges, the individual in question should not have their name drug through the mud publicly. When a judge says something should be sealed prior to, during, or after a trial, he or she undoubtedly has good reason for that as well, and leaking such information is an inexcusable abuse of the justice system.

Did House Speaker Mike Hubbard abuse his office?

Who knows?

But I’ll tell you what is frankly a lot more terrifying than anything Hubbard is accused of: Realizing that your state government’s attorneys are apparently willing to do whatever it takes to “get you,” if they decide they want you, for whatever reason.

Criminals should live in fear of the long arm of the law and the impartiality of the American justice system.

But in Alabama, the AG’s office has turned into a quasi-Secret Police force able to wield the ultimate power of the government to do as it pleases.

How is it that Alabama’s elected attorney general is able to unleash unelected state employees to prosecute cases that could be politically advantageous to him? And when chaos ensues he, what, throws his hands up and says “but I recused myself”?

This is not what justice looks like, at least not in America, and certainly not in Alabama.

Welcome to Alabama: Where alleged criminals are prosecuted by alleged criminals https://t.co/HpRr01mNgz #alpolitics

— Cliff Sims (@Cliff_Sims) February 3, 2016