COVID-19 cases have spiked across Alabama, hitting our state’s low-income and African American counties with a vengeance. Perry County now has per-capita infection rates exceeding peak levels in New York City, while Lowndes County – with its long, storied history of civil rights’ struggles – has also suffered enormously.

Throughout the country, telemedicine grew astronomically during the pandemic; patients and practitioners have turned to virtual video “visits” to avoid the risks of face-to-face discussions. But those without home computers are effectively shut out of these services.

Both our values and our concern for public health demand we close this divide. Closing the digital divide should be part of the long-overdue national reckoning on social justice.

Meeting this challenge is going to take cooperation and creativity, not finger-pointing and political posturing. Elected officials need to get skin in the game if we are going to bring broadband to those who need it for critical services such as telehealth.

First, we need to get broadband infrastructure into rural communities. Nationwide, 95% of all communities are wired for broadband. But big infrastructure gaps still exist across swaths of rural America, where longer distances and fewer potential customers make network infrastructure a lot more expensive to build. Twenty-seven percent of rural Alabamans currently don’t have fixed broadband deployed in their neighborhoods.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) will soon start distributing $20 billion in new funding for rural broadband projects, which is a good start. Rep. Jim Clyburn (D-SC), the majority whip and highest-ranking African American in Congress, is leading a bipartisan effort in both Houses to speed up that FCC program, while getting rid of outdated eligibility restrictions that limit competition, steer buildout projects to favored contractors, and keep many capable providers on the sidelines.

More competition and better oversight should help avoid the poor performance seen in earlier federal broadband programs, when too many dollars were spent non-competitively and went to areas that already had broadband infrastructure rather than unserved rural communities with the greatest needs.

Second, we need to get more people online in the communities where high-speed service is already available. Twenty-seven percent of Americans still don’t subscribe to home broadband service even though broadband providers have stepped up with heavily discounted or even free service for low-income customers. In federal surveys, 60% of non-subscribers say they just don’t have any need or interest in-home broadband.

It will take a sustained, united effort to change these misguided views on the importance of broadband. Community groups, health advocates, local governments, and tech and broadband companies all need to join together in a public-private partnership to accomplish universal digital literacy by a date certain.

We need to do a much better job evangelizing broadband connectivity to those who don’t think the internet is important to them. Broadband opens lots of doors – educational, economic, health care and much more. Telemedicine can literally save lives, and broadband can vastly expand the quality of life in many other ways. We need to tell this story more compellingly to get everyone signed up.

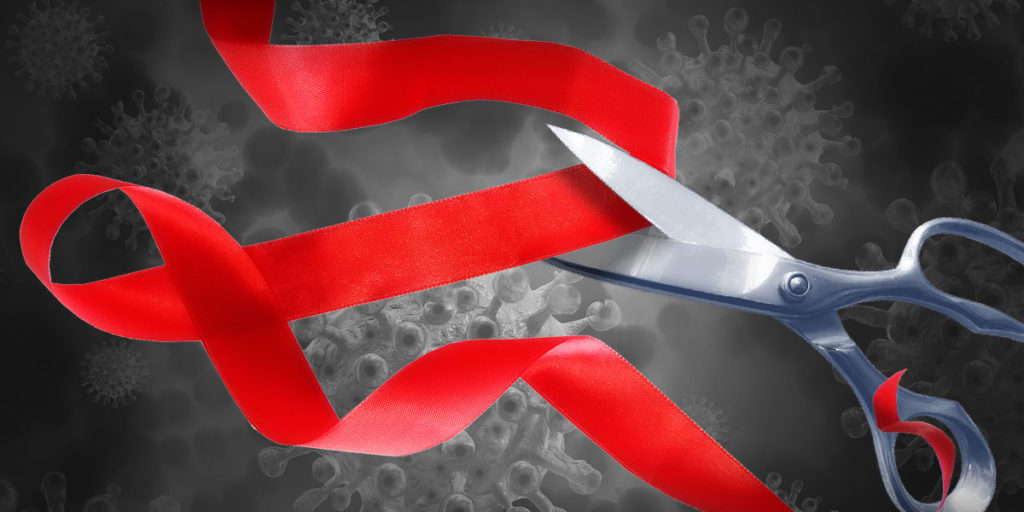

Third, we need to permanently dismantle obsolete public policies that discriminate against telemedicine. When the pandemic hit, federal agencies quickly (if belatedly) relaxed restrictions on telemedicine and expanded reimbursements for telehealth services under Medicare and other federal health programs. Alabama followed suit with new, temporary licensing rules and Medicaid reimbursements. Instead of letting these reforms expire when conditions return to “normal,” federal and state governments should make these temporary policies permanent.

Healthcare providers across Alabama recognize the potential for remote, broadband-connected telemedicine services to revolutionize health care delivery and close access gaps.

I teamed with several local doctors to start the Telemedicine Hub of Alabama – an online service through which patients can access low-cost primary care, mental health care, and pharmacy services. Remote services like these are particularly critical to reach patients in areas impacted by hospital closures; 17 hospitals across Alabama have closed in the last decade.

We need public policies and public-private partnerships that encourage innovation and investment. And we need better rural broadband infrastructure and higher broadband adoption rates to ensure every Alabamian can access telemedicine apps and services.

This will take an investment of time, resources, and leadership – but we can crack this code if all the stakeholders work together. The long-term health of Alabamians depends on it.

Curtis Cannon is Managing Partner of Axis Recovery, a Birmingham based strategic healthcare consultancy firm