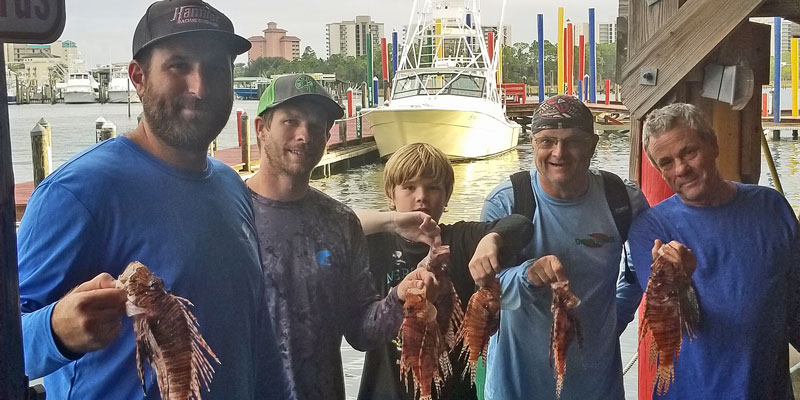

The red lionfish population off the Alabama Gulf Coast is a little smaller now that the second of two spearfishing tournaments finished a two-week run, with the final weigh-in last weekend at Tacky Jack’s in Orange Beach.

An invasive species from the Indo-Pacific, lionfish have spread throughout Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic waters. Lionfish compete with native reef fish for food resources, and holding spearfishing tournaments is one way to mitigate the invasion.

In 2019, the Coastal Conservation Association of Alabama and the Poarch Band of Creek Indians served as sponsors and provided $10,000 each for the lionfish tournaments. The Alabama Marine Resources Division (MRD) and Alabama Spearfishing Association provided support, while the Alabama Reef Foundation distributed the prize money. The tournament payout was based on the number of pounds of lionfish harvested during the event.

Josh Livingston was the top spearfisherman in the lionfish category at the most recent event and took home $1,779 for bringing 279 pounds of lionfish to the weigh-in. David Murphy was the overall Master Spearfisher at the Orange Beach Open.

Livingston spends a great deal of time diving for lionfish, harvesting for the commercial market and research work for several educational entities.

Livingston brought in about 650 pounds of lionfish at the first tournament in the spring. He said the number of fish he spotted over this past weekend was definitely reduced. An ulcerative skin disease has been observed in lionfish, especially in Florida, and Livingston thinks that may be a reason for the reduction.

“Normally, we see 30 to 40 fish per site,” Livingston said. “We’re seeing 15 to 20 now or less. That’s great news. They’re still out there, just not as many. But I did shoot 79 fish on one dive during this tournament.”

Livingston has no doubt the increased prize money will boost participation.

“If there is money involved, people are going to go after them,” he said. “If they can subsidize what they’re doing, paying for fuel or buying a new speargun, they’ll do it.”

Chandra Wright of the Alabama Reef Foundation said the foundation understands the threat lionfish pose to the native reef fish species in the Gulf.

“They are voracious eaters and are competing with our commercially and recreationally important species, like red snapper, grouper and gray triggerfish,” Wright said. “We want to do as much as possible to protect our reefs and native species. So having great partners, like the Poarch Band of Creek Indians and CCA Alabama who donated $10,000 each, gives us a great incentive for divers to bring in lionfish.”

Chas Broughton of the Alabama Spearfishing Association sees a great future for the lionfish tournaments when more divers find out about the cash prizes.

“I believe the new money incentive is helping to bring in more divers,” Broughton said. “If we can do it for another year or two, I think we’ll see it grow much larger. We just need to get the word out to more divers. We probably picked up 10 or more divers for this tournament.”

Craig Newton, MRD’s Artificial Reefs Program Coordinator, said lionfish were introduced to the south Atlantic waters in the late 1980s when Hurricane Andrew caused significant destruction in south Florida. One or more homes in Andrew’s path had aquariums with red lionfish. Andrew swept away the homes and the lionfish were released into the wild.

“Through DNA genetic work, the lionfish population we have in the Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic is traced back to about eight females from that initial release,” Newton said. “So, the thousands and thousands of lionfish we have today in the Gulf and South Atlantic originated from that handful of females.”

The red lionfish first showed up off the coast of Alabama in 2009. Although there had been rumors of lionfish, the first hard evidence came when a diver speared a lionfish at the Trysler Grounds about 25 miles south of Orange Beach.

Starting in 2013, Marines Resources began directed monitoring efforts to get an idea of how many lionfish actually existed in Alabama waters.

“The trend is that the majority of reefs that are deeper than 100 feet of water have lionfish,” Newton said. “They do occur in waters shallower than that but not in alarming numbers. We have a few documented cases of lionfish inshore around Perdido Pass and Old River. Typically, the turbidity of Gulf waters just offshore of Mobile Bay tends to push the lionfish away from the mouth of Mobile Bay. They prefer higher salinity and clearer waters. They don’t seem to be extremely tolerant of sudden changes in water temperature. Lionfish can be found 1,000 feet deep. Those waters are real cold, but they’re real stable. Inshore, the water temperature changes pretty quickly. In the winter, those inshore temperature changes will cause them to leave or die.”

The MRD monitoring started with SCUBA diving surveys and evolved into diving and ROV (remotely operated vehicle) surveys that could monitor much deeper water.

“The high definition cameras on the ROVs allow us to not only evaluate the reef fish population but also include lionfish,” Newton said. “Over the past couple of years, we have seen a significant trend. From 2009 to 2016, there was a significant increase in the abundance of lionfish from year to year. Then from 2016 to present, those numbers seem to have stabilized.”

To mitigate the invasion of lionfish, the Alabama Seafood Marketing Commission has marketed the table fare of lionfish with its white, flaky meat. The lionfish filets can be prepared in variety of ways from raw, sashimi-style, to battered and fried like white trout, for example.

Participating in lionfish tournaments is also part of MRD’s mitigation effort. Newton said more research will have to be done to determine how effective these methods are.

“The lionfish tournaments and marketing of lionfish for table fare could have had an effect on the population, or it could mean the lionfish have reached carrying capacity within our waters,” Newton said. “The predator fish have not evolved to prey upon the lionfish with their venomous spines, so the carrying capacity is related to food resources and habitat rather than any control from predation.

“They do compete with our native reef fish. They eat a lot of the same items that vermilion snapper, lane snapper and red snapper do. They do eat crustaceans, but a large part of the diet are small finfish, just like the snappers. The lionfish is something we’re going to have to learn to live with. We’re never going to get rid of them. We’re just hoping we can handle the impact from them.”

Newton said lionfish spawn numerous times and release the eggs in a gelatinous mass that is poisonous. The egg mass floats in the current until the fry disperse to the ocean bottom. As they near maturity, they move to some type of structure, whether natural bottom or artificial reefs and petroleum platforms.

Lionfish don’t get nearly as large as the snapper, topping out at about 3 pounds. Typically, a mature lionfish will range from ¾ of a pound to 3 pounds. Obviously, it’s the number of lionfish on each reef that becomes a problem. That is one reason the tournament organizers decided to change the format for the last tournament of the season.

At the spring tournament, prize money went to the first three places and in a random drawing for any spearfisher who brought in a certain amount of lionfish.

“The strategy for the second tournament was to incentivize more people to target lionfish,” Newton said. “The idea was that the average diver who may not shoot lionfish would be encouraged to shoot lionfish. This tournament was based on a bounty. Prize money, $10,000, was awarded based on the number of pounds of lionfish weighed in. This way, each competitor would get some type of prize money. The rate of return would basically be how much effort you put forth to shoot lionfish. This prize structure enables even the novice spearfisher to target lionfish to pay for gas or entry fee money or tank fills. We had 45 competitors and some of those wouldn’t have targeted lionfish at all if it hadn’t been for the prize money provided by CCA Alabama and the Poarch Band of Creek Indians.”

David Rainer is an award-winning writer who has covered Alabama’s great outdoors for 25 years. The former outdoors editor at the Mobile Press-Register, he writes for Outdoor Alabama, the website of the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.