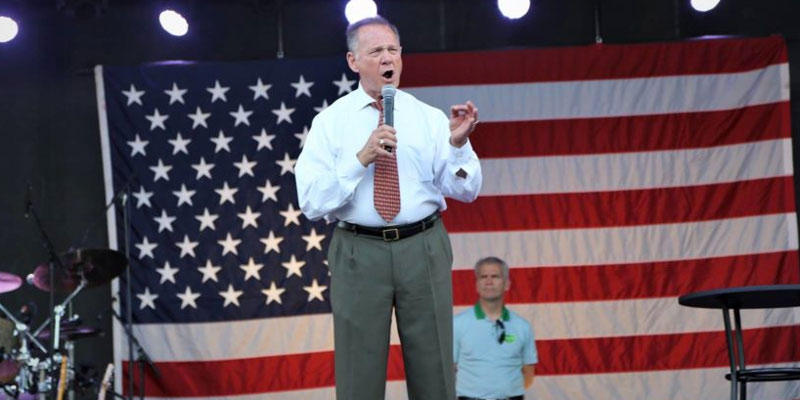

Roy Moore and his team are getting a taste of their own poison this week, but that doesn’t make the poisoning justified.

Democratic Senate candidate Doug Jones’ latest ad highlights three Alabama Supreme Court cases in which then-Chief Justice Moore “sided” with defendants accused of sexual crimes involving minors. The obvious implication is that Moore sympathizes with such sexual abusers because he is one.

It’s not necessarily – in fact, it’s likely not – a fair use of those cases. It is, however, the exact same sort of out-of-context (mis)use of court cases that Moore’s team engaged in earlier this year to help torpedo the possibility for Alabama’s own federal appeals court judge Bill Pryor to be nominated for the U.S. Supreme Court. It was wrong for Moore’s team to take Pryor’s cases out of context, and it is wrong for Jones’ team to do it to Moore. (Note: In one of those columns linked above, I wrote that I thought Moore’s team was behind the slams at Pryor. I later confirmed that Moore-connected lawyers indeed were helping lead the charge.)

Moore’s associates bizarrely accused Pryor of being “a strong ally of the homosexual lobby” merely because Pryor’s decisions (or dissents) in three cases happened to reach “results” favored by homosexual parties to the case. I joined some conservative legal luminaries in explaining how viciously unfair the accusation was, because in all three cases Pryor’s legal reasoning was plain for all to see, and it hewed closely to the actual facts at hand and the specific procedural issues involved.

Good judges don’t rule according to the policy results they desire, but according to how the exact language of existing law applies to the exact circumstances of the case – and, whether an observer agreed with Pryor’s conclusions or not (I disagree with one of them), it was obvious those conclusions were reached by using conservative, textualist reasoning.

Moore’s team was wrong to take the cases out of context in order to do a political hit job on Pryor.

Likewise, Jones’ team is wrong if it is taking Moore’s three cases out of context in order to do a political hit job on the judge. My preliminary analysis (not a full one yet) indicates this is likely what is happening here.

Jones’ ads highlight three cases in which Moore’s ruling favored the defendant in sexual abuse cases. Yet, just as what happened in particular with one of Pryor’s cases, all Moore did in one of the cases was argue a procedural point rather than address the merits of the defendant’s guilt or innocence.

The case involved a 37-year-old mentor at the Mobile Youth Advocate Program who had been convicted of sexual acts with two teenage girls. The case was a he-said/they-said case, without clear physical evidence. The defendant wanted to argue that the two girls’ relationship with each other, and his reporting of that relationship to their parents, led them to concoct their accusations against him. The trial judge had not allowed the defendant to mention part of those (alleged) dynamics to the jury.

The state high court split on the case. Five ruled the trial judge was right to exclude the argument; Moore and two others dissented. It obviously was a close call. To somehow insinuate that Moore’s dissent showed that he doesn’t care about child sex abuse is to also make that same insinuation against his colleagues, including the widely respected, solidly conservative Justice Glenn Murdock, who joined the dissent. That’s ludicrous.

Another case involved similar arguments about whether the accuser’s sexual history could be relevant, admissible evidence in another he-said/she-said case. Again, Moore was joined by two other justices in his dissent. In this case and the prior one, a closer parsing of the circumstances might help determine if Moore’s principles and reasoning seem correct or not, but they surely don’t, in themselves, show a weird predilection in favor of sexual criminals.

The third case looks more questionable, especially since Moore was the lone wolf arguing the technical legal point favored by the defendant while all eight of his Supreme Court colleagues ruled otherwise. The case involved a 17-year-old male with supervisory authority who sexually abused a 12-year-old boy. Moore agreed that the conviction on one count should stand, but argued that the other count should be dismissed because the particular statute used for that conviction applied only if a full adult used “force,” rather than a mere position of authority, in a case in which there was “abuse of children by other children.” In his explanation, though, Moore took care to say that such behavior is “an abhorrent crime and should be strictly punished” – but only under terms specified by the Legislature.

To use the vernacular: Ick. Yuck. This is clearly a case where Moore’s legal hair-splitting, whether legally correct or not, makes one just want to look away.

Still, all of which leaves the question open as to whether Jones is fair to insinuate that Moore’s overall record shows Moore to be strangely and uniquely sympathetic to those who commit sexual abuse. The New York Times analyzed the record and found that while “he sided with the accused in sex abuse cases more often than his colleagues did,” there also were three cases in which he did just the opposite, siding with prosecutors in sex-abuse cases while a majority of his colleagues sided with the accused.

And the Times – surely not a Moore sympathizer – noted that Moore’s concern for defendants applied not just for accused sexual abusers but also for the procedural rights of defendants in many other sorts of cases too. In addition, reported the Times, “Mr. Moore has expressed concern over the years about mandatory life sentences for nonviolent crimes, and once suggested that a death row inmate might not be getting a fair shake in the court system.”

Matthew Clark, a lawyer who worked for Moore, explained to the New York paper: “He had no love for criminals, but he believed that every defendant was entitled to due process of law. He saw many cases where the defendants, especially young black men, would be convicted solely on very weak circumstantial evidence.”

Clearly, the overall context does not support the insinuations in Jones’ ad. Even if one believes the somewhat credible allegations about Moore’s own long-ago sexual behavior, that doesn’t mean his rulings as a judge have shown bizarrely pro-abuser bias.

Considering the intellectually dishonest way that Moore’s legal henchmen attacked Judge Pryor earlier this year, it might be argued that the Jones ad is a sort of cosmic justice and that Moore is being hoisted with his own petard. This initial response is morally untenable. The kindergartener’s wisdom is also profoundly correct: Two wrongs don’t make a right.

Moore has flaws, maybe major ones. But this ad unfairly invents a flaw that probably doesn’t exist.

Yellowhammer Contributing Editor Quin Hillyer, of Mobile, also is a Contributing Editor for National Review Online, and is the author of Mad Jones, Heretic, a satirical literary novel published in the fall of 2017.