“Everywhere you looked, there was devastation.”

So recalled Dr. T.L. Lewis, the longtime pastor of Bethel Baptist Church in Birmingham’s Pratt City community.

“From one end of Pratt City to the other, lives were lost, homes and businesses were destroyed. Our church was leveled to the foundation.”

But in the immediate aftermath of the deadly tornado that struck early on the evening of April 27, 2011, the destruction of his church was secondary to meeting human needs, Lewis said. “Some people lost everything they had, including their clothes. Starting that night, we knew we had to get busy getting people what they needed just to survive.”

By noon the following day, the office of then-Birmingham Mayor William Bell helped Lewis secure use of the former Scott Elementary School in Pratt City, just off U.S. Highway 78. The building was situated ideally for use as a relief and recovery center, and work to prepare it for opening the following morning began immediately, Lewis said.

Those preparations included a call to Alabama Power, which provided generators to supply electricity to the building. By morning on April 29, donations of clothing, shoes, toiletries, children’s toys, nonperishable food, bottled water and other items had been sorted and placed in separate rooms. There was also a room where residents could register for federal aid and other available assistance.

“We worked all night long,” Lewis remembered. “And we never stopped. For a long time, it was Scott School from morning to evening every day except Sunday, when we went to church.”

With its sanctuary and other facilities destroyed, even going to church was a different experience for the congregants of Bethel Baptist. Soon after the tornado, the church settled into an interim home at a former strip mall just up U.S. 78 in Adamsville, with room for its administrative and educational functions as well as Sunday services.

“That was a blessing,” Lewis said. “It gave us a place to be while our church house was rebuilt. But more than that, it helped us understand more fully what it takes to recover from a disaster.”

Lewis is quick to note that Pratt City was far from the only community in the Birmingham area – and across Alabama – to feel the brunt of that day’s severe weather outbreak. The National Weather Service recorded 62 confirmed tornadoes in Alabama, with as many as 252 deaths connected to the day’s storms, according to official sources.

In Jefferson County, the day began with an early-morning EF2 tornado that touched down in Cahaba Heights and caused 20 injuries. The tornado that struck Pratt City was an EF4 monster, generating wind speeds that approached 200 mph as it tracked more than 80 miles through Greene, Tuscaloosa and Jefferson counties. All told, the storm that carried that one tornado resulted in 65 deaths – 22 of those in Jefferson County – along with more than 1,500 injured.

Alabama April 2011 tornadoes remembered: Pleasant Grove’s day of destruction from Alabama NewsCenter on Vimeo.

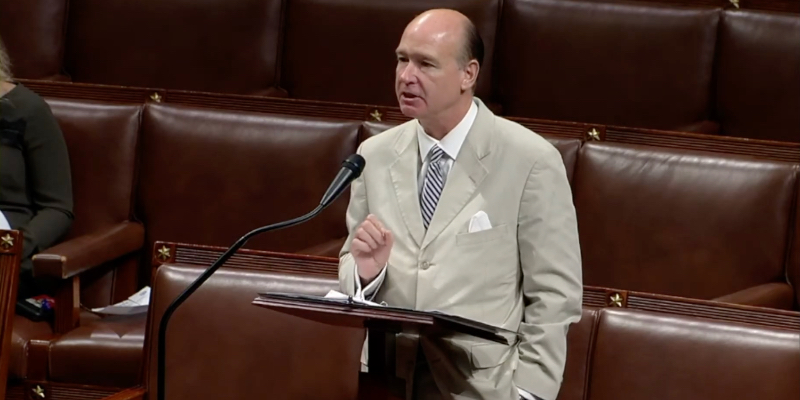

“Concord, Hueytown, Pleasant Grove, McDonald Chapel, Pratt City, Fultondale,” Jefferson County Commissioner Joe Knight recounted, verbally tracking the tornado’s path. He was in the Jefferson County Emergency Operations Center (EOC) early that morning, and Knight said, “it was clear pretty quickly what we might be in for.”

Knight had been in office for less than six months, and it was trial by fire in his first experience as the commissioner with oversight of the EOC. After spending most of the day with his assistant, reaching out to constituents to help ensure preparedness, Knight returned to the EOC and heard the latest on the path of the storm that already had done major damage in Tuscaloosa. He remembers going onto the parking deck above the EOC at Birmingham City Hall and seeing the massive, rain-wrapped cloud approaching the city from the southwest.

“It was eerie,” he said. “We started to feel sand pellets, grit hitting our faces, so we got on back inside. And then all hell broke loose.”

The next day, Knight was back on the road, surveying the damage in some of the hardest-hit areas. He said it was only then that the full scope of what had happened began to sink in.

“You see a thousand pictures. But pictures don’t compare to being there, seeing the devastation surrounding you, listening to people who have lost their homes and seen their communities just horrendously damaged.

“We got updates on confirmed deaths, and every time, you looked around and didn’t know how the number wasn’t higher,” Knight said.

As bad as the damage was, he said he was struck even more by the community spirit that was already asserting itself on that morning after. Beyond the work of organizations like the American Red Cross and the Salvation Army, an influx of money, services, relief supplies and volunteers came from both public- and private-sector sources, as well as from the faith community and other organizations and individuals. In that sense, he views the days, weeks and months after that April 27 as a point of pride for the entire community.

“Everywhere I went that day I saw people of all races and cultures coming from their communities to respond to the needs of other communities. I saw people helping people, neighbors helping neighbors. It was magnificent,” Knight recalled.

Lewis agrees. He said the storm taught valuable lessons about “togetherness and common purpose.” It also taught some lessons about patience and perseverance: Bethel Baptist operated the Pratt City recovery center for more than two years after the tornado. The church rebuilt on the same spot it stood before, opening its new facility in 2014.

In 2019, officials and community leaders unveiled a visible symbol of Pratt City’s ongoing recovery, with the opening of One Pratt Park, a six-acre city park adjacent to the rebuilt Pratt City branch of the Birmingham Public Library, which had been damaged by the tornado. Funded by disaster recovery funds made available by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the park includes playgrounds, a walking track, a 200-seat amphitheater and a 4,500-square-foot building with kitchen facilities and meeting space for neighborhood events and other activities.

“You don’t recover overnight,” Lewis said. “Storms can be terrible, but we also see that some good things can come of them.

“They can help bring us closer together. They can inspire us to be better than we were before — as individuals, as neighbors and as a community.”

(Courtesy of Alabama NewsCenter)