Look up at the sky tonight. Every star you see — plus hundreds of thousands, even millions more — will come under the intense stare of NASA’s newest planet hunter.

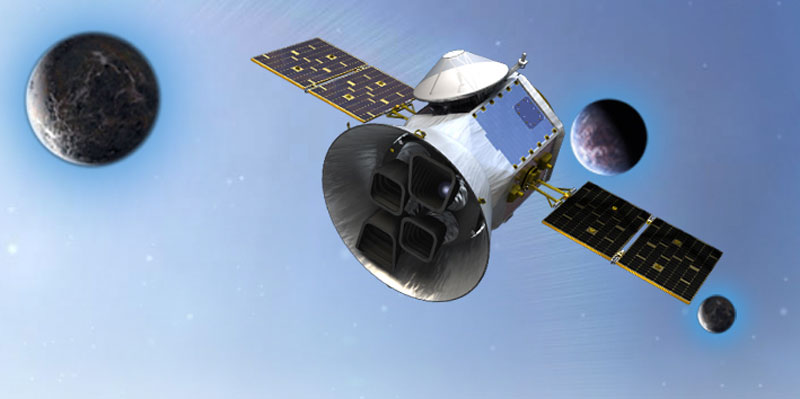

Set to lift off early next week, the Tess spacecraft will prowl for planets around the closest, brightest stars. These newfound worlds eventually will become prime targets for future telescopes looking to tease out any signs of life.

It will be the most extensive survey of its kind from orbit, with Tess, a galactic scout, combing the neighborhood as never before.

“We’re going to look at every single one of those stars,” said the mission’s chief scientist George Ricker of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Scientists expect Tess to find thousands of exoplanets — the term for planets outside our solar system.

“All astronomers for centuries to come are really going to focus on these objects,” Ricker said. “This is really a mission for the ages.”

NASA’s astrophysics director, Paul Hertz, said missions like Tess will help answer whether we’re alone — or just lucky enough to have “the best prime real estate in the galaxy.”

Tess — short for Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite — is the heir apparent to the wildly successful Kepler Space Telescope , the pioneer of planetary census. Kepler’s fuel tank is running precariously low after nine years of flight, and NASA expects it to shut down within several months.

Still on the lookout from on high, Kepler alone has discovered more than 2,600 confirmed exoplanets. Even more candidates await confirmation.

The exoplanet count, from all observatories in space and on Earth over the past couple of decades, stands at more than 3,700 confirmed with 4,500 on the strong contender list.

About 50 are believed to potentially habitable. They have the right size and the right orbit of their star to support surface water and, at least theoretically, to support life.

Most of the Kepler-identified planets are so far away that it would take monster-size telescopes to examine them more. So astronomers want to focus on stars that are vastly brighter and closer to home — close enough for NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope to scrutinize the atmospheres of planets lurking in their sun’s shadows. Powerful ground telescopes also will join in the detailed observations, as well as enormous observatories still on the drawing board.

MIT’s Sara Seager, an astrophysicist who has dedicated her life to finding another Earth, imagines water worlds waiting to be explored. Perhaps hot super Earths with lakes of liquid lava. Maybe even rocky or icy planets with thin atmospheres reminiscent of Earth.

“It’s not “Interstellar” or “Arrival.” Not yet anyway,” she said, referring to the recent hit science-fiction films.

The total mission price tag for Tess is $337 million.

Fairly small as spacecraft go, the 800-pound, 4 foot-by-5-foot Tess (362-kilogram, 1.2 meter-by-1.5 meter) will ride a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Liftoff is scheduled for Monday evening. Its eventual orbit of Earth will stretch all the way to the orbit of the moon.

“It packs a big punch, and that’s the part that we’re really excited about,” Ricker said.

Tess’ four cameras will zoom in on red dwarf stars in our cosmic backyard — an average 10 times closer than the Kepler-observed stars. The majority of stars in the Tess survey will be 300 light-years to 500 light-years away, according to Ricker. (A light-year is about 6 trillion miles, or 9 trillion kilometers.)

Red dwarfs are the most common stars around and, as their name implies, relatively small. They’re no more than half the size of our sun. They’re also comparatively cool in temperature. The celebrated Trappist-1 star, with at least seven Earth-size terrestrial planets, is an ultra-cool red dwarf that’s just a little bigger than Jupiter.

So how do you spot a planet around such a small, faint star, from so far away?

A planet should cause a slight, brief dip in its star’s brightness as it passes right in front. Tess will detect any such blips.

The spacecraft will survey almost the entire sky, starting with the Southern Hemisphere for a year, then the Northern Hemisphere for a year. Even more years of scanning could follow.

Scientists speculate that the habitable or so-called Goldilocks zone — the distance from a star where it’s neither too hot nor too cold to support life, but just right with the potential for liquid water at the surface — should be much closer to red dwarfs than it is in our own solar system. The orbits of any planets in these systems should be fairly short.

NASA and others stress that Tess will not look for atmospheric or other signs of life; it can’t do that.

That all-important job will be left to Webb, the next-generation successor to the Hubble Space Telescope that’s grounded until at least 2020, and even bigger observatories yet to come.

If life, indeed, is detected out there — be it microscopic or some higher form — scientists like to think robotic explorers would be launched from Earth for closer inspections.

NASA project manager Jeff Volosin notes the technology for reaching these faraway worlds — or even communicating — doesn’t yet exist.

“For me, just knowing they’re there would be enough,” Volosin said. “Just knowing that you’re not alone.”

(Associated Press, copyright 2018)