Tony Pace and Mary J. Cox fell in love in rural Clarke County, but since they were an interracial couple and it was 19th century Alabama, marriage was not an option.

So, in the parlance of modern slang, they “shacked up.” That got them indicted in November 1881 on charges of living together in a state of adultery or fornication. And since Pace was black and Cox was white, the penalties were more severe than if they both had been the same race. After conviction, a judge sentenced both to two years in prison.

Pace challenged the conviction and lost at the Alabama Supreme Court and then took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

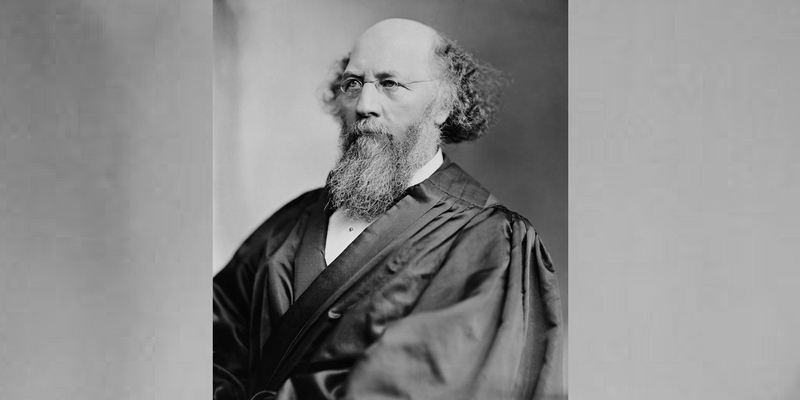

On Jan. 29, 1883 — exactly 135 years ago today — a unanimous high court ruled that the conviction and sentence handed down to Pace did not violate the Equal Protection Clause. Even though the penalties were more severe because the couple was interracial, the justices reasoned, Cox and Pace both received the same punishment.

“Whatever discrimination is made in the punishment prescribed in the two sections is directed against the offense designated, and not against the person of any particular color or race,” Justice Stephen J. Field wrote for a unanimous court. “The punishment of each offending person, whether white or black, is the same.”

Historians contend that the decision not only cemented miscegenation laws nationwide for nearly a century but laid the groundwork for future rulings upholding the “separate but equal” doctrine that justified racial segregation, such as the court’s ruling 13 years later in Plessy v. Ferguson. That upheld racially segregated rail cars.

“It’s the law of the land from the 1880s until the 1960s,” said Peter Wallenstein, a history professor at Virginia Tech. “Pace is a really important case, equal in its own way to Plessy. … Throwing that out took very heavy lifting.”

Julie Novkov, chairwoman of the political science department at the University of Albany, State University of New York, agreed.

“It basically closed the door to challenges of these kinds of policies for many years. This case was actually quite pivotal,” she said in an interview.

Wallenstein, author of the 2002 book “Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law—An American History,” said that many subsequent court rulings adopted the reasoning that laws that treated races differently were constitutional as long as they equally punished white and black violators.

“That’s a symmetrical argument that held sway for a long time,” he said.

Pace v. Alabama did not get relegated to the ash heap of history until 1964, when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned it in striking down a similar law in Florida. Three years later, in the famous Loving v. Virginia case, the justice made clear that states could not prohibit mixed-race couples from getting married, either.

Until the 1960s, civil rights advocates mainly shied away from challenging the Pace precedent, even as they were busy attacking other discriminatory laws.

In “What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America,” historian Peggy Pascoe notes that a Montana lawyer contacted the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in 1946 seeking help on behalf of a client in challenging that state’s miscegenation law. Officials at the legal arm of the venerable civil rights organization responded that the Pace case “had already foreclosed” that issue.

“There was a sense that education discrimination was an easier case to make,” Novkov said. “The NAACP was very shy about these kinds of cases.”

Novkov, author of “Racial Union: Law, Intimacy, and the White State in Alabama, 1865-1954,” said there are indications that the justices, themselves, thought laws touching on race and sex were a hot potato. She noted that months after the court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, the justices declined to hear another miscegenation case from Alabama.

A black woman named Linnie Jackson was convicted for her relationship with a white man, A.C. Burcham. The Alabama Court of Appeals upheld the conviction, citing the Pace precedent.

Interracial relationships in Alabama, while not exactly commonplace, were not exceedingly rare in the late 19th century. In addition to the smattering of prosecutions attesting to their existence, Wallentein said there is evidence in the historical record that authorities did not uniformly enforce the law.

“There were countless couples, by the hundreds, by the thousands,” he said.

Wallenstein said it is unclear how Pace’s relationship with Cox came to the attention of law enforcement officers, but he added that it is a good guess that someone turned them in.

Novkov said many interracial couples avoided detection by living discreet lives.

“It was happening kind of under the radar screen,” she said.

Novkov said prosecutors generally concentrated on mixed-race couples whose relationships resembled marriage. She said they usually did not bother with one-off sexual relationships. In fact, she added, court records indicate that defendants sometimes beat charges by arguing that they had no meaningful relationships, only sex, with members of another race.

“Clearly, some of these relationships lasted the length of people’s lives, because there were disputes over wills,” she said.

Brendan Kirby is senior political reporter at LifeZette.com and a Yellowhammer contributor. He also is the author of “Wicked Mobile.” Follow him on Twitter.