The small, tired house with peeling white paint once served as a refuge for Rosa Parks in Detroit. It has traveled across the world and back in an odyssey conceived by an artist and a Parks family member determined to preserve the civil rights activist’s legacy.

It was rescued for $500 off a demolition list, then disassembled and shipped to Germany, and was supposed to be the centerpiece of a weeks-long exhibition at Brown University this spring: an American homecoming amid a national conversation surrounding race, history and the value of certain monuments. Instead, the Ivy league school abruptly canceled.

Parks’ niece, Rhea McCauley, calls it a rejection of Parks and her legacy. But with the looming possibility that the house would come all this way and never be seen, the community has stepped in. Volunteers are working to reconstruct the home as much as possible so that it can be displayed to the public for free Saturday and Sunday, Easter weekend.

Berlin-based artist Ryan Mendoza calls the two-day show “Farewell Rosa Parks: Outcast in Your Own Country.” Once it’s over, he will have to take the house apart quickly and ship it elsewhere, possibly back to Germany if he cannot find an American home.

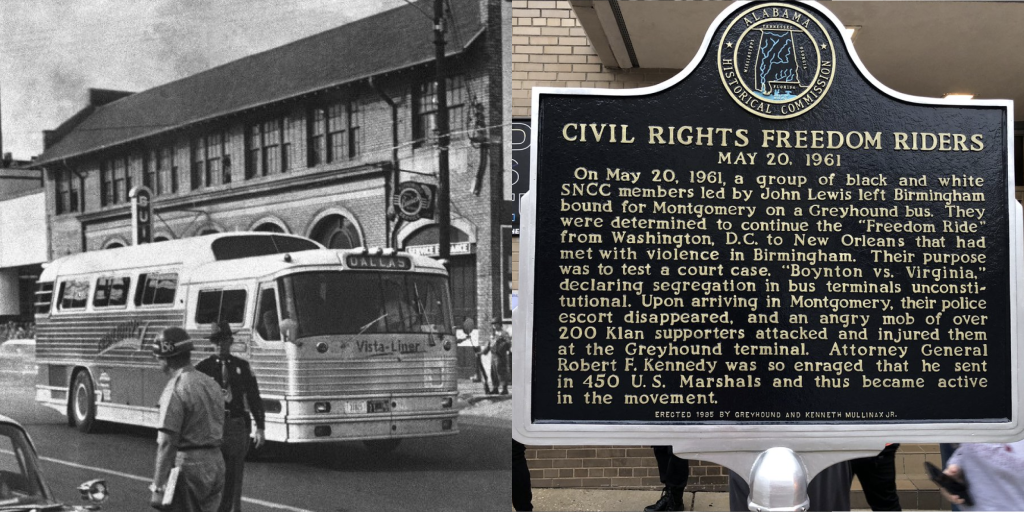

To escape death threats, Parks moved to Detroit in 1957, two years after her defining act of defiance: refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white passenger in Montgomery, Alabama. She lived in the tiny house in Detroit with her brother and his family and struggled to make a new life for herself. The family says Parks lived there with 17 other relatives.

It was abandoned and slated for demolition after the financial crisis in 2008 and Detroit’s dramatic decline, but McCauley instead bought it from the city for $500 and donated it to Mendoza, an American. After unsuccessful efforts trying to persuade the city to help save the building, Mendoza in 2016 carefully dismantled it and moved it to the German capital, rebuilding it on the lot of his studio.

Despite being tucked away in an obscure location, the home drew daily visitors , many traipsing into the parking lot of the neighboring apartment building to get a frontal view of from the other side of a small fence.

It was almost as if only taking the house out of its context showed people its real value, Mendoza said.

“This was the real success of the project in my eyes,” he said. “So many people learned who Rosa Parks was and what she did in her life, and how important one person is, that you don’t have to be a giant in order to effect change.”

But the delicate structure was exposed to the elements in Berlin. Mendoza and McCauley were determined to bring it home, and display it indoors where it would be protected from vandals and the weather. Mendoza was drawn to Brown University because it has publicly acknowledged how it benefited from the slave trade.

It took weeks for Mendoza and two architects to gingerly dismantle the house, neatly stacking and cataloguing each piece of the warped and cracked planks of cedar cladding. Then, it was shipped back across the Atlantic in two containers and brought to the WaterFire Arts Center in Providence, where they began to rebuild.

But earlier this month, Brown canceled, citing an unspecified dispute involving the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development, which Parks co-founded but which has feuded with relatives for years. A lawyer for the institute has questioned whether Parks’ time there was significant, calling it “an unimportant blip in the timeline of her life here in Detroit.”

“The ‘house’ is simply not a human interest story,” Steven Cohen told The Associated Press in an email.

Mendoza, McCauley and many members of the Rhode Island community disagree. In the house, they see the story of so many African Americans who migrated north, only to face redlining and other discrimination that has affected generations of black Americans.

Malia Quirindongo, 18, who was volunteering with the group YouthBuild Providence to reassemble the house this week, said what she has learned about its story shows that the country doesn’t value Parks as it should.

“They were going to knock her house down, and sold it for $500 when they have hotels where presidents have stayed for one night yet there’s plaques talking about ‘he stayed here’?” Quirindongo said. “They’re going to knock down a house that is to someone who is so important in this country, and in history? It’s eye-opening.”

Mendoza still hopes he can find a place for the house in America. He and McCauley wonder if the country just isn’t ready to examine this uncomfortable part of its past.

“I would like for this house to have a home,” McCauley said. “This is a story that’s a larger part of American history. It cannot be overlooked.”

(Associated Press, copyright 2018)