We have experienced unprecedented economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing policies. Twenty-two million Americans lost jobs in four weeks. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis projects potentially 30% unemployment and a 50% decline in GDP by June. This looks like a depression, but is it really?

A recession or depression is visible – idle factories, reduced investment, and unemployed workers – but the causes are typically numerous and elusive. An economy in a depression is like a motor that has stopped working. Economists also note that recessions extend across most of the economy, as opposed to being a slump in one sector. The oil bust of the mid-1980s, for example, did not produce a recession.

Our current slump meets the breadth requirement. While sectors like tourism and entertainment have been particularly hard hit, the 30% decline in global oil demand demonstrates widely reduced economic activity. The stock market tumbled over 30% as well, consistent with a broad slump.

Yet in a very important way, the COVID-19 slump, dubbed by some the Great Suppression, differs from recessions and depressions; the decline has resulted from closing businesses to stem the virus’ spread. Christmas Day, when GDP craters as most factories, stores and restaurants close, perhaps provides a more appropriate economic analogy. The Christmas shutdown is intentional; people do not want to work and businesses oblige. Is the COVID-19 slump a lengthy Christmas break?

If so, we could expect a vigorous rebound when we end government closures, just as on December 26 (or perhaps January 2). We do not fear the economy not returning to normal after the Christmas shutdown.

The aftermath of World War II provides another hopeful example. Many of America’s factories produced tanks, planes, ships, and munitions for the war. Measured GDP was high but consumption of goods and services was modest. Economists were unsure the economy would transition to peacetime production after fifteen years of limited consumer production due to the Depression and the War, but it did.

One important difference exists between the COVID slump and the Christmas crash: we plan and prepare for Christmas. The COVID crash was unanticipated and of uncertain duration. Households did not stock up on supplies or accumulate extra savings. The Federal government did not run budget surpluses ahead of the crisis.

In addition to Christmas, small businesses often close when the owner goes on vacation, and seasonal businesses survive months-long closures. How and when will the Great Suppression turn into a recession? Most likely when currently shuttered companies go out of business, or their employees take other jobs.

Closed businesses have no revenue to pay employees, their rent, or for leased equipment. They may potentially hibernate and come back to life. Laid-off employees may have few other job options and landlords may lack new paying tenants. The Payroll Protection Plan and supplemented unemployment will hopefully help businesses hibernate and not go bankrupt.

The pandemic has two distinct components: reduced economic activity as people try to stay safe, and government closure of non-essential businesses. These two actions occurred nearly simultaneously and now complicate business owners’ calculations. When states lift stay-at-home orders, will customers return to restaurants and gyms? The existence of COVID-19 will significantly alter our economy. Previously successful business may be unprofitable until we have a vaccine or cure.

Business owners must also evaluate a political uncertainty. In March we chose public health over the economy. If COVID-19 cases increase after states ease restrictions, will we choose public health again? If so, then owners may squander their savings reopening businesses which get closed a second time.

Business failures will have ripple effects. Landlords will feel financial hardship as businesses and tenants are unable to pay rent. Loans made to these businesses will go unpaid. The ensuing rounds of spending reductions will not be directly connected to the closed businesses. The shutdown will have become a recession or depression and it will be too late to “reopen” the economy.

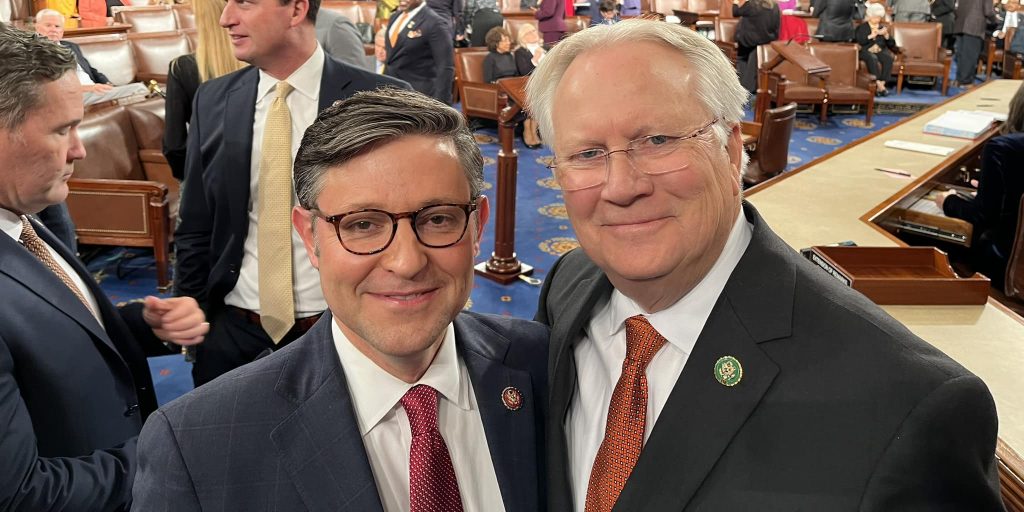

Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.