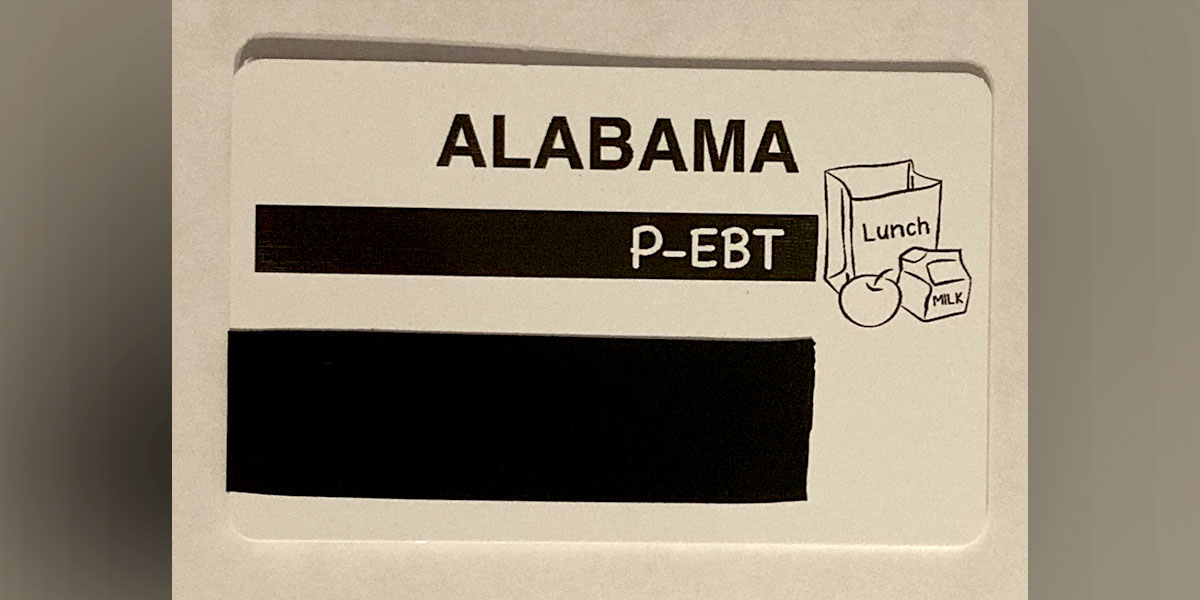

Two of my children recently received something in the mail called a Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer debit card, known as a P-EBT, each loaded with $375.

The accompanying letter explained that the money was for school children in grades K-12 who were enrolled in the National School Lunch Program — free and reduced lunch — during the 2020-2021 school year but who missed those meals while schools were closed due to COVID-19.

But here’s the problem: my income exceeds the eligibility ceiling for such a thing, and even so, my children weren’t actually enrolled in the program during the 2020-2021 academic year… because they weren’t even enrolled in public schools at all!

They attended a private school, and we packed or paid for their lunches ourselves.

I smelled the stench of government waste, followed it back to its source, and this is what I found:

In early May of 2020, P-EBT cards began being mailed to thousands of eligible students in Alabama, according to a news release from the Alabama Department of Human Resources, which oversees the distribution of the cards with assistance from the Alabama Department of Education.

The state announced last April that a second round of benefits would be issued, and advisories posted in June, August, and December stated additional funds would be distributed across the state.

A spokesman for the Alabama Department of Human Resources told me that 460,958 students received more than $144,279,786 in benefits for the 2019-2020 school year. For the following school year, 2020-2021, he said that 477,172 students were issued $326,682,316 in benefits, and when the summer months were added, the total for the year increased to 503,040 students and $507,913,066 in funds.

That’s a little more than $652 million in benefits distributed across 19 months.

So how did $750 of that end up in my mailbox?

Records provided by the Department of Human Resources show that Conduent State & Local Services of Washington, D.C., was issued a contract to manage distribution of the cards. While records show various costs for the contract, past, and potential, the department’s spokesman told me that it cost approximately $11 million to distribute the cards.

But the data — the actual names of those who are eligible and the amount of the financial benefit they should receive — came from the Alabama Department of Education.

Now, remember back to the spring and summer of 2020. We didn’t know how bad the pandemic was, how long it would last, and what we needed to prepare for.

People were hoarding toilet paper. It was crazy out there.

And against that backdrop, school officials were trying to not only get meals to those who had already signed up for the free and reduced lunch program but the thousands more who signed up since the pandemic began.

I spoke with the director of the Alabama Department of Education’s Child Nutrition Program and the department’s spokesman. They both described a chaotic and confusing process of collecting and sorting through those existing and incoming accounts while at the same time navigating the process of moving to a new student data management system.

Records show that during the 2020-2021 school year, 347,663 students in Alabama’s public schools were enrolled in the free and reduced lunch program. But as the Department of Human Resources spokesman stated, 477,172 students were provided with P-EBT benefits for that year, and a total of 503,040 when you count the summer.

That’s a pretty big difference, somewhere between 129,509 and 155,337 students.

And if each of those received the $375 that my children did (which all depends on how long each student’s school was closed), that’d be anywhere between $48 million and $58 million.

Officials said that some of the difference can be explained by counting the private schools that are enrolled in the free and reduced priced lunch program, residential childcare institutions, and those who were added to the program during the effort to provide meals to families during the pandemic, though all were still required to meet eligibility requirements. It’s just not clear what those numbers are, precisely.

It was a “pretty messy situation” the Alabama Department of Education’s spokesman said, while the department’s Child Nutrition Program director said some of the numbers required “finagling.”

To be charitable, that was a sign of the times in 2020. People did their best with the challenges they faced and the resources and information they had.

Elaine Waxman, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, studied the national program and explained in a Washington Post story that states were faced with a massive knowledge management problem.

“Centralized databases for this kind of information were very uncommon, and departments of education were not set up to collect and monitor these types of data,” Waxman said.

I cut through my P-EBT cards with a pair of scissors and mailed them back to the distributor with a note explaining that my children weren’t eligible. The spokesman for the Alabama Department of Education said he hoped others in my shoes would do the same. While I share his hope, I’m not very confident about that, especially since the total at the grocery store check-out has increased 7.5% due to inflation in the last year alone.

One of the arguments conservatives make against big government programs is that they’re simply too big for anyone to manage properly — regardless of their experience, resources, or intent. You can add the P-EBT program to the long line of evidence for that argument.

Still, the federal government has extended the program, and state officials told me that they’re currently exploring the option, though no decision has been made.

First, the program should be paused, if not stopped altogether. The list of eligible students from 2020-2021 cannot be trusted as the basis to distribute so much money.

Secondly, the solution to feeding students who are enrolled in the free and reduced lunch program is to KEEP SCHOOLS OPEN.

We can forgive the mistakes of the past, especially since it was a crisis. But education is supposed to be about learning.

And we can start by learning from our mistakes.

J. Pepper Bryars is a conservative opinion writer from Mobile who lives in Hunstville. Readers can find him at https://jpepper.substack.com.