Before Rosa Parks was “the first lady of civil rights” and “the mother of the freedom movement,” she was a 42-year-old Montgomery, Ala., resident who simply believed the color of her skin should not limit which seats she could occupy on a public bus.

On Dec. 1, 1955, Parks was sitting in the “colored” section of the bus on her way home from work when the “white” section ran out of room. Since the early 1900s, bus drivers had been empowered by a Montgomery city ordinance to assign seating to segregate the bus by race. Although it was not part of the law, it became commonplace for drivers to push blacks further to the back of the bus when the white section became too crowded. They sometimes even removed them from the bus entirely.

When the bus driver, James F. Blake, told Parks and three other black passengers to move, she declined, although the other three complied.

“When that white driver stepped back toward us, when he waved his hand and ordered us up and out of our seats, I felt a determination cover my body like a quilt on a winter night,” she later recalled.

Blake called the police and had her arrested.

“People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true,” she said. “I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Parks was bailed out of jail the next day.

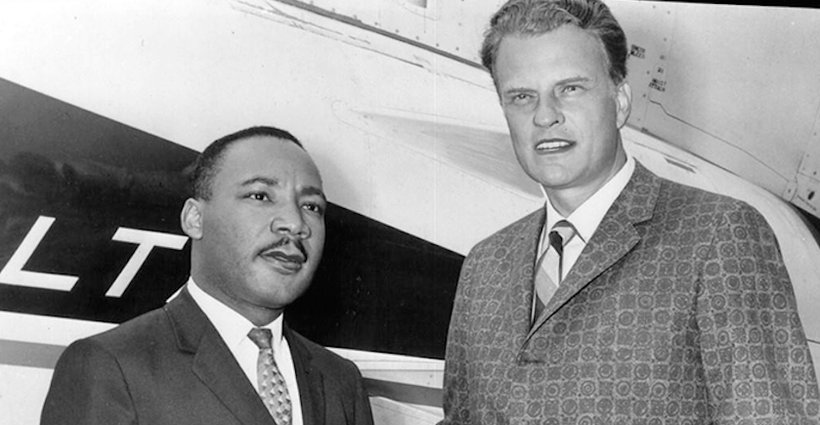

Four days later, on Dec. 5, 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott began. That evening, after the one-day boycott’s success, an organization formed to continue its efforts elected a young minister named Martin Luther King, Jr. to be its leader.

Just over a year later, December 21, 1956, the Montgomery public transit system was legally integrated.

Rosa Parks–police report filed against her–Montgomery, Alabama, tomorrow 1955: #NARA pic.twitter.com/DUH3dH5vJe

— Michael Beschloss (@BeschlossDC) December 1, 2014