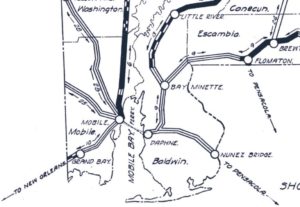

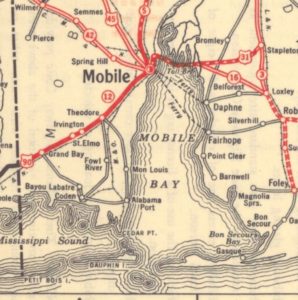

For well over a hundred years, southwest Alabamians have grappled with getting from Mobile across the Mobile Bay to Baldwin County and back, and that is a problem that predates the founding of the state.

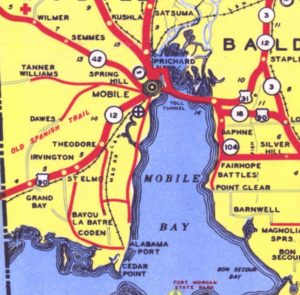

If you have made that journey recently, you would know there are a number of ways to cross the bay. Most people use Interstate 10, which includes the Wallace Tunnel to get to a series of bridges known as the Bayway. Some use U.S. 90-98, which consists of the Bankhead Tunnel and the causeway built in 1926.

Another option is the Cochrane–Africatown USA Bridge, the designated truck route, to get to the Causeway or the Bayway via Prichard.

For those with a little more time, you opt to head north on Interstate 65 and cross the “Dolly Pardon Bridge,” then head back south to Spanish Fort. Finally, if you’re feeling up for a scenic excursion, you can head down to Dauphin Island and take a $16 ferry ride to Fort Morgan across the Mobile Bay.

Either way you go, the 400-plus square mile geographic water barrier is evident. And now in 2018, all those routes are inadequate for the area’s transit needs.

In the early days of automobile transportation in Alabama, the primary means to get from Mobile to Baldwin County’s Eastern Shore was by ferry. It was expensive, and that made Baldwin County isolated from Mobile.

In 1927, the Cochrane Bridge, a vertical lift bridge, opened. It connected Mobile to the newly built Causeway, and ultimately ferry transit was no longer needed.

Other east-west means of crossing the Mobile River opened in the decades to follow. The Bankhead Tunnel came in the 1940s, providing a more direct approach than the Cochrane Bridge to the Causeway from downtown Mobile.

In the 1970s, both I-10 and I-65 were completed, offering travelers those two routes from the north and east into the city.

The latest addition to crossing the Mobile Bay came in the early 1990s with the cable-stayed Africatown-Cochrane Bridge that replaced the above mentioned Cochrane vertical lift bridge.

Even with all these means to cross Mobile Bay, traffic is still an issue for the primary route, which is the Interstate 10 Bayway. At the time of the construction, the Eastern Shore cities of Spanish Fort, Daphne and Fairhope in Baldwin County weren’t expected to be the bedroom communities for Mobile that they are today.

Now in addition to the usual east-west traffic that is making the trek on I-10 to points anywhere from Jacksonville, Fla. to Los Angeles, Calif. you have commuters headed back and forth from home to work.

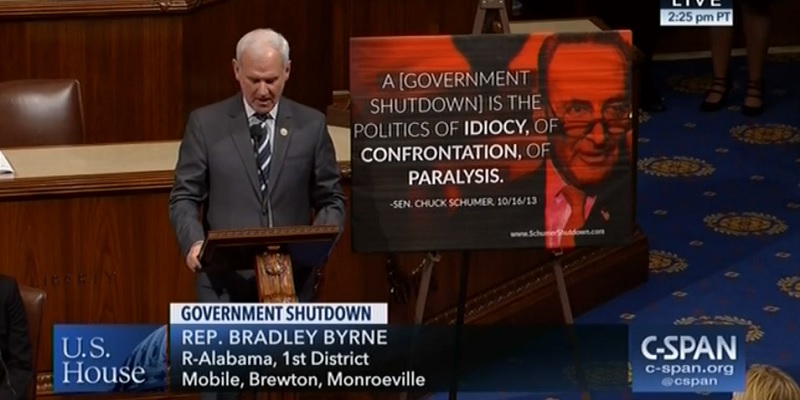

Tuesday in an appearance on Mobile radio’s FM Talk 106.5, Rep. Bradley Byrne (R-Fairhope) hinted the latest iteration of the solution to crossing Mobile Bay could be part of President Donald Trump’s infrastructure plan.

Byrne told host Sean Sullivan that Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao was familiar with the region’s need for a new crossing but was waiting to see if it would indeed be part of Trump’s plan.

“I can’t give you the precise particulars because we haven’t seen the president’s infrastructure plan,” he said. “But I think you’re going to see the president – we’ll be working with him and the Department of Transportation prioritizing our bridge project because it fits exactly in with what he’s trying to do.”

Given the state would have to offer up a portion of the financing for the bridge, a new I-10 bridge will likely include a toll, Byrne said.

“Yes, it will be [a toll bridge] because the state is trying to come up with its money and the state’s been very clear that they’re going to come up with their money by putting the toll on the bridge.”

If completed as a toll bridge, the new I-10 bridge would be Alabama’s most significant toll project by far.

There are already a few toll bridges in Alabama – bridges crossing the Alabama and Tallapoosa Rivers north of Montgomery, the Joe Mallisham Parkway near Tuscaloosa and the Foley Beach Expressway headed from mainland Baldwin County to Orange Beach.

A new toll I-10 bridge would easily dwarf these projects in size given the amount of traffic it would serve. The latest figures estimate at least 53,000 automobiles in both directions enter in and out of the western side of the Wallace Tunnel daily, and that is likely to increase.

Will this bridge be enough to last at least for the next 100 years?

Given the prior solutions have not lived up to long-term expectations (at least by highway standards in the United States), one has to ask if in the year 2050 the government will once again be seeking another solution.

Whatever the current solution is, it is long overdue. Accidents on I-10 headed in and out of the Wallace Tunnel are a daily occurrence that results in traffic backing up several miles.

Even though it wasn’t a big issue in the last U.S. Senate special election, making a new I-10 bridge priority is something voters in Mobile and Baldwin Counties, the second- and sixth-most populous counties respectively, could be swayed by in the upcoming gubernatorial election later this year.

Jeff Poor is a graduate of Auburn University and works as the editor of Breitbart TV. Follow Jeff on Twitter @jeff_poor.