When it comes to protests, America has lost its senses.

A previous column of mine provided a single example, from southern Alabama last week, of an overreaction to a silent, respectful protest. That one example is indicative of a larger problem, on both sides of the protest equation.

The overly broad (but accurate) description of the problem is that both protesters and responders get too hyped up about public demonstrations. The overly facile (but still appropriate) correctives to the problems are to better calibrate protest means and ends, to better calibrate responses thereto, and to remember that respectful demonstrations are far more effective at earning support for one’s causes than are abusive or violent ones.

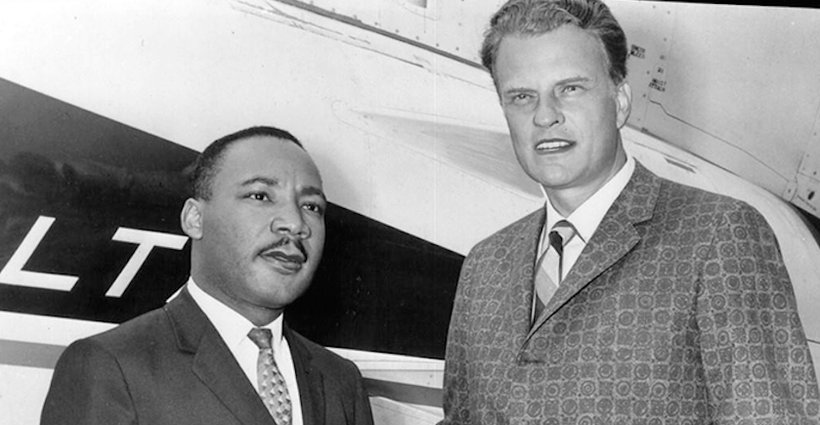

Martin Luther King Jr. had it right when he insisted that demonstrations be non-violent. People quietly clutching their Bibles merit more sympathy than people wielding billy clubs.

The 1950s-60s civil-rights movement did something else right: They targeted their actions to the proximate cause of their distress. If they were disallowed to order from a lunch counter, they sat in at that counter. If they were told not to ride in the front of the bus, they took front-row seats.

But they didn’t otherwise inconvenience, much less threaten or harm, uninvolved innocents. They didn’t use anger at a lunch counter as an excuse to break store windows across the street. They didn’t use separate water fountains as justification for looting. Their supporters didn’t shout down speakers at public forums or try to physically block access to the venues.

In short, they acted like civilized human beings, not like wanton, cowardly, juvenile delinquents worthy of no more respect than plague-bearing sewer rats in heat.

Oh – and when they didn’t immediately get their way, they didn’t go crying for safe rooms with stuffed animals and Play-Doh.

On the flip side, those targeted by non-abusive protests must show some restraint and perhaps a little humor – and they darn well should not turn something non-violent into a physical altercation. Right now, we have a president who acts as if every protest against him is akin to a crime against humanity, and who spent his campaign repeatedly urging violent reactions – by police and private citizens as well – as the first resort even against rather mild-mannered demonstrators.

Perhaps taking cues from him, or perhaps just as part of the general zeitgeist of tribalism and societal intolerance of any opinion dissenting from one’s own, more and more crowds at public events act as if signs or symbols of opposition are illegitimate or even criminal, rather than merely expressions of disagreement.

So we have college hoodlums reacting violently to mild-mannered guest speakers. We have presidential candidates telling crowds to send protesters to the hospital. We have thugs in black masks starting riots over basically nothing. And we have innocent counter-protesters mowed down on public streets.

These are all indices of what is supposed to be “civil society” spiraling down into uncivil anarchy. All year long, we’ve seen an appalling lack of observance of the rules of Protesting 101, and a lack of tolerance (rightly understood) and temperance among protesters and responders alike.

Almost all of the examples of protesters and responders behaving badly earlier this year – and last year, too – involved far more serious abuses, on at least one and sometimes both or all sides, than the relatively mild disrespect for proper norms evidenced in Baldwin County earlier this week. The disrespect this time came entirely from one side, the responders; the protesters themselves acted well within the American tradition.

Still, it’s worth positing that if there are rules of Protesting 101, there should be rules of Handling Protests 101. The first rule is that if something is advertised as an event open to the general public, then respectful protesters among that public should be allowed to attend, too – as long as they do, indeed, behave well, making their point without unduly interfering with the experience of other attendees. The second rule is that respectful protest should be seen neither as insult nor threat, but as somewhat welcome (even if also somewhat annoying) attempt at dialogue.

The third rule is that non-abusive behavior should be met with non-abusive response, and non-violent behavior with non-violent response. Rule 3A is related: Proportionality and restraint should rule the day in general, not just in terms of the physical responses to the demonstrations, but in terms of tone of voice, diction, and body language.

And the fourth rule is the most important: This is America, fergoshsakes. We’re supposed to cherish free expression, not quash it. Whatever else we think of Thomas Jefferson (I still revere him), every one of us should be a Jeffersonian in believing that we should “tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.”

So, come on, everybody: Chill out, and get a grip.

Yellowhammer Contributing Editor Quin Hillyer, of Mobile, also is a Contributing Editor for National Review Online, and is the author of Mad Jones, Heretic, a satirical literary novel published in the fall of 2017.