August 25th of this year marks the centennial of my father’s birth, and the occasion offers an appropriate opportunity for us to reflect not only upon his life and career but upon the history of our state, as well.

Born seven years before Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic, George C. Wallace grew up in a rural portion of Alabama that, in many ways, was still recovering from the Civil War and the Reconstruction period that followed.

Among the traditions of his era was the practice of racial segregation, a system that had been in place for generations and one that would ultimately prove to be both wrong and indefensible, but to many Alabamians, it was the accepted way of everyday life.

It was a system that my father and thousands of other elected officials throughout the Deep South states fought to preserve, but unlike others, he sought to retain it through peaceful, methodical and more temperate measures.

My father was certainly defiant, charismatic, and energetic in his battle against what he perceived as a threat from the central government to control every aspect of our lives, but he was never violent.

He understood as both a well-educated attorney and as one of the greatest politicians this or any other state has ever produced that violence and bloodshed would harm his cause, not help it. And, as a Christian, he instinctively knew in his soul that violence was wrong.

He ensured the University of Alabama campus was swept clean of any item that could be used as a weapon prior to his “Stand In The Schoolhouse Door” at Foster Auditorium because he wanted to avoid the same violence that occurred when Ole Miss University was integrated.

Every stick, stone and pebble was methodically removed from the grounds of the Quad, and soft drink machines that dispensed bottles were replaced with ones that filled paper cups. In order to further quell trouble, he appeared on statewide television the night before student registration and implored citizens to stay away from campus and allow him to be their spokesman.

The result of his efforts was the peaceful and non-violent integration of the University.

He later became good friends with the two students who eventually made history on that hot June day. James Hood invited my father to attend his graduation when he received his doctorate from the University of Alabama, and Vivian Malone Jones was among the honored guests at his state funeral in 1998.

There are those who wrongly suggest without one scintilla of evidence that he commanded Alabama State Troopers to charge the marchers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge. He, in fact, ordered Col. Al Lingo and Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark to protect the marchers if they crossed the bridge while he contacted President Johnson and requested federal troops to provide security throughout their 50-mile trek to Montgomery.

The late Montgomery Advertiser reporter Bob Ingram was in the Governor’s Office when news of the violence at the Edmund Pettus Bridge was received, and he later wrote extensively that my father was enraged as he stormed around his office and said, “This is the last thing I wanted!”

In today’s climate of extreme political correctness and strident advocacy journalism, those who seek to tell my father’s story focus almost exclusively on the tragedy in Selma and the events of 1965 and prior, but that is not where his journey ended.

It is, in many ways, where the most important journey of his life began.

Though he was a leader in preserving the Old South custom of segregation, he was an equally determined advocate of progress and racial reconciliation once the antiquated way of life was dissolved.

My father famously appeared at a meeting of African-American ministers at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Dr. Martin Luther King once led the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and he told them he was wrong to defend such an outdated tradition. He also met and spoke privately with leaders like Rev. Joseph Lowry, Congressman John Lewis, Jesse Jackson, and others and candidly discussed his error of judgment.

There is no doubt that the redemptive example he set led millions of Alabamians – many of them the parents, grandparents and great grandparents of those who are reading this column – to accept, adapt and embrace the dramatic social and cultural changes, as well. I know that my sisters – Lee and Peggy, as well as Bobbie, who passed away in 2015 – share that belief.

Southerners of all races are a devout people with a deep sense of forgiveness, which is evidenced by the fact that my father was elected to his final terms as governor with the overwhelming votes and political support of the African-American community. He, in turn, appointed more minorities to office than any governor before or, very likely, since.

Let us not forget that my father offered forgiveness just as dramatically as he sought it when he quietly wrote a letter to the man who shot five bullets into his body and confined him to a wheelchair. He told his assailant, “Please seek our Heavenly Father because I love you, and I am going to Heaven, and I want you to be going, too.”

Throughout the past 100 years, my father’s journey and our state’s history have largely paralleled each other. Both moved from the aftermath of the Civil War to the promise of Civil Rights. Both traversed the often difficult path from segregation to integration. And both had the courage to change and embrace new truths.

Judging the Alabama of today by the grainy black-and-white images captured during the height of the Civil Rights Movement more than 50 years ago does a disservice to our state.

Judging my father’s life, career and legacy without viewing the entirety of his journey does the same disservice to him because the truth he ultimately embraced and nurtured is the truth we should all embrace today.

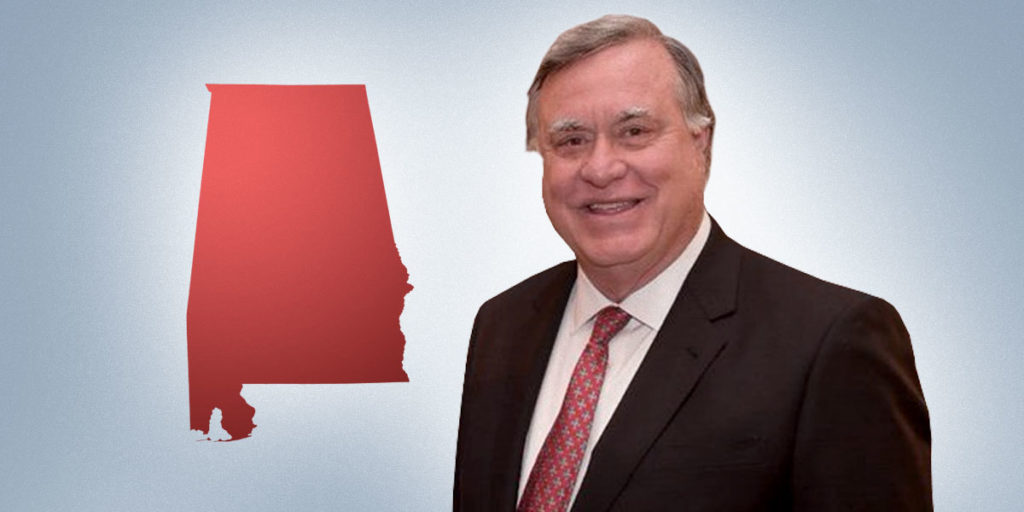

George Wallace Jr. is the son of Alabama Govs. George and Lurleen Wallace. He previously served two terms as Alabama State Treasurer and two terms as a member of the Alabama Public Service Commission.