One of the net benefits of academia’s obsession with Nelle Harper Lee and her classic novel “To Kill A Mockingbird” is the exhaustive research done about her life and how she arrived at creating the idealistic imaginary cult figure in Atticus Finch.

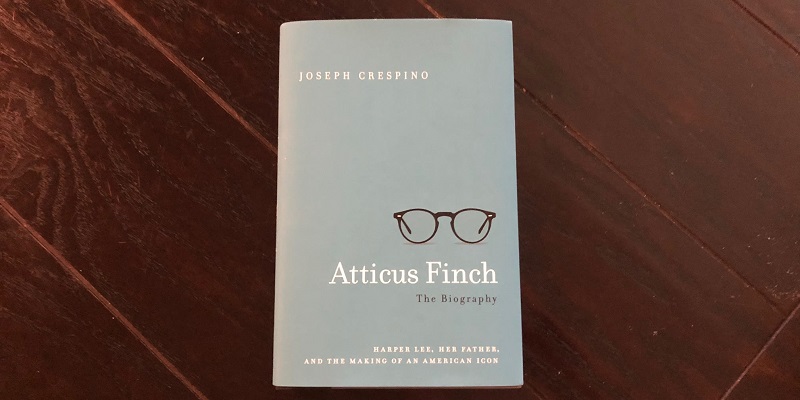

In his recently released book “Atticus Finch: The Biography,” Emory University history professor Joseph Crespino has undertaken the daunting task of doing a deep dive into former Alabama legislator and newspaperman Amasa Coleman Lee, the father of Harper Lee.

The elder Lee was widely believed to be the inspiration for Atticus Finch given the parallels between “To Kill A Mockingbird” protagonist Jean Louise “Scout” Finch and author Harper Lee.

With Crespino’s book, we learn how A.C. Lee arrived in Monroeville from his birthplace in nearby Georgiana and his early life in the Florida panhandle’s Chipley, Fla.

We also learn about Harper Lee’s struggles with the development of “To Kill A Mockingbird” and Atticus Finch. It was years in the making and the Atticus Finch that America knows only came after Harper Lee’s first efforts in the later-published follow-up “Go Set a Watchman.”

Crespino’s effort to try to find the beginnings of Atticus Finch, who takes on an entirely different persona in “Go Set A Watchman,” offer a glimpse of how small-town Monroeville fit in the broader ecosystem of Alabama politics.

During A.C. Lee’s time as part of Monroeville’s political hierarchy, the Black Belt-Big Mule coalition still ruled the roost in state politics. Monroe County was not a part of that coalition.

Monroeville itself was one of those places cut off from the outside world, given the railroad and the Federal Road were off to the east, and the Alabama River was off to the west. It was one of those places to which you had to be going because it wasn’t on the way to anywhere.

The geographical isolation made Monroeville cut off from the rest of the world.

Enter A.C. Lee. For 18 years, Lee served as the editor of the storied Monroe Journal, which coincided with a pivotal time in America. The nation was in the throes of the Great Depression. Some of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs were implemented to target Southern poverty specifically.

Racism was alive and well in Alabama, and often there would be a conflict with any massive federal intervention like the New Deal and the status quo in the South.

What Crespino offers to readers is the importance of a figure like A.C. Lee in a place like Alabama during the first half of the last century. A.C. Lee ran The Monroe Journal before there were television sets in every home, even before radio was a thing in that part of Alabama and long before the Internet.

Therefore, people in places like Monroeville had to rely on newspapers like The Monroe Journal for all of their news. That’s a much different model today where the smaller newspapers have ceded coverage beyond their county lines to larger outlets.

Lee’s role was important because he could take the hard-to-understand state, national and international news of the day and deliver in a way for local readers. Crespino’s thorough review of The Monroe Journal showed A.C. Lee was long on hot takes, but he knew who his audience was.

Readers are also reminded of the friction between Lee and long-time Monroe County probate judge, E.T. “Short” Millsap. Millsap, who has his own place in the Monroe County Courthouse-turned-museum, was one of the many small-town political bosses that were a part of Alabama politics during that era.

The county probate judge was, and remains to this day in Monroe County and a few other Alabama counties, the de facto head of county government. A character resembling Millsaps makes a cameo in “Go Set a Watchman,” as the book’s William Willoughby, which Crespino explains.

Beyond the history of Alabama life at the time, Crespino gives readers details about the progression of “To Kill a Mockingbird” and how the rise of the book and the blockbuster movie fit in with the timing of the Civil Rights era. He shows it as a valuable example of how politics are downstream from culture, to borrow a phrase from the late Andrew Breitbart.

Where Crespino may lose readers is his tedious effort to link Harper Lee to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s civil rights activism and his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” It is true that King references Atticus Finch in his book “Why We Can’t Wait,” but the effort to try to associate the two drags on and in some ways seems forced.

Beyond that, you can learn a lot about Alabama and how the political and media culture in this state arrived where it is today from this 184-page read.

Crespino does Alabamians a service with his thorough look at the writings in The Monroe Journal under A.C. Lee and his “Atticus Finch: The Biography” is the textbook model for anyone considering a deep dive into any other forgotten era and place in Alabama.

@Jeff_Poor is a graduate of Auburn University and is the editor of Breitbart TV.