Like millions of Americans across the nation, my family and I were shocked, angered and saddened by the video that documented the death of George Floyd while in custody of Minneapolis police officers. Anyone who reviews the footage quickly understands that it was a tragic and negligent death and could have easily been avoided.

In the weeks since, inspiring peaceful protests have been organized in countless cities, towns, and crossroads as the power and promise of the First Amendment has been put on full display.

At the same time, major metropolitan areas have also experienced rioting, looting, arson and acts of violence that run counter to Mr. Floyd’s memory and the opportunity for meaningful, peaceful change that this moment in history offers.

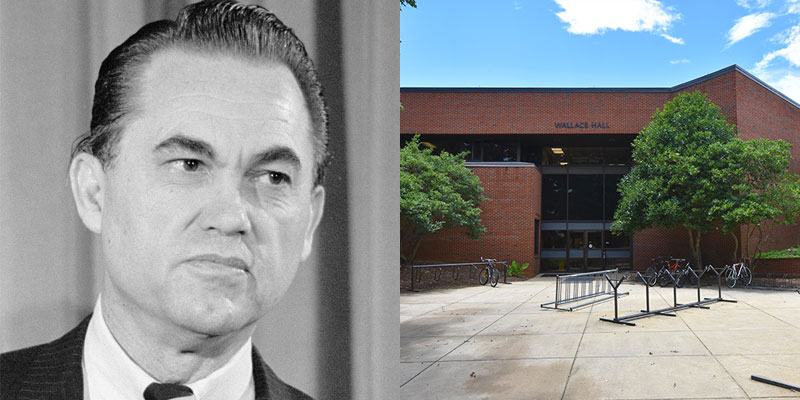

Accompanying the protests have been calls by some to remove and dismantle long-standing historical monuments, markers and statues, and a petition to erase the name of my father, former Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace, from a campus building has been circulated at Auburn University.

It is my firm belief that many of those who signed the Auburn petition are improperly focusing upon only one era of my father’s career, and when the full prism of his life is viewed, it becomes evident that his story, like so many of those born in his era, offers an inspiring message of transformation, reconciliation, and acceptance.

I would submit to Auburn President Jay Gouge and other campus leaders that the fundamental change and progress my father’s life represents should be celebrated and emulated today, not vilified.

Born seven years before Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic, George Wallace grew up in a rural portion of Alabama that, in many ways, was still recovering from the Civil War and the Reconstruction period that followed.

Among the traditions of his era was the practice of racial segregation, a system that had been in place for generations and one that would ultimately prove to be both wrong and indefensible, but for many Alabamians, it was the accepted way of everyday life.

Even within that fatally flawed system, the personal, one-on-one regard that my father endeavored to offer people of all races was considered an anomaly. Pioneering African-American attorneys like J.L. Chestnut and Fred Grey have said my father was the only circuit judge that penalized prosecutors who did not address them respectfully, and they noted that his rulings were based upon the merits of the case, not by skin color.

As governor, he did famously seek to enforce segregation at the University of Alabama in 1963, but in doing so, he successfully avoided a repeat of the violence that occurred when Ole Miss University was integrated just a year prior.

He later became good friends with the two students who eventually made history on that hot June day. James Hood invited my father to attend his graduation when he received his doctorate from the University of Alabama, and Vivian Malone Jones was among the honored guests at his state funeral in 1998.

There are those who wrongly suggest that my father commanded Alabama state troopers to charge the marchers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge on what has become known today as “Bloody Sunday.” The late Montgomery Advertiser reporter Bob Ingram was in the governor’s office when news of the violence was received, and he later wrote that my father was enraged as he stormed around his office and said that Col. Al Lingo had violated his commands.

In today’s climate, many of those who seek to tell my father’s story focus almost exclusively on the tragedy in Selma and the events of 1965 and prior, but that is not where his journey ended.

It is, in many ways, where the most important journey of his life began.

Though he was a leader in preserving the Old South custom of segregation, he was an equally determined advocate of progress and racial reconciliation once the antiquated way of life was dissolved.

He often met with leaders like Rev. Joseph Lowry, Congressman John Lewis, and Jesse Jackson to candidly discuss his errors of judgment, and he spoke from the pulpit of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church to apologize to congregants for past actions.

A close friend of Edgar Daniel “E.D.” Nixon, the African-American Pullman car porter who chose Rosa Parks as the test case against segregation laws and selected the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to lead the Montgomery Bus Boycott, my father was asked to serve as a pallbearer at his funeral.

He was elected to his final terms as governor with the overwhelming votes and political support of the African-American community, and he, in turn, appointed more minorities to office than any governor before or since.

Many have surmised that the attempted assassination in 1972, which left my father confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life, helped him more fully understand the pain he had brought to others. Perhaps there is a kernel of truth in that assumption.

There is no doubt that the redemptive example he set led millions of Alabamians – many of them the parents, grandparents, and great grandparents of those who are reading this column – to accept, adapt, and embrace dramatic social and cultural changes.

Shortly after my father’s passing in 1998, Rev. Jesse Jackson wrote a condolence letter to my sisters and me that makes the argument more powerfully than I could ever attempt. A portion of his letter read:

“I saw a repentant Wallace in his latter years – a transformed man for the good. I saw a man with greater vision of inclusion – walls replaced by bridges, bridges which lead to open doors, doors which lead to change in education, health care, and equal opportunity for people black and white who were left behind … George Wallace deserves forgiveness, redemption, and restoration.”

The college students and young activists who are signing the petition to remove my father’s name from Wallace Hall will make many mistakes in their lives, just as all of us have. Some of those mistakes will be significant, some will be embarrassing, and some may very well hurt and affect others in ways they never intended.

I hope beyond hope that no one judges the entirety of their lives solely by the mistakes they made, but, rather, by the lessons they learned from them, the good deeds they accomplished, and the progress they made as people in the great arc of life.

Doing otherwise would be unfair to them.

And denying my father the same consideration and balanced judgment does a disservice to his life and legacy, as well.

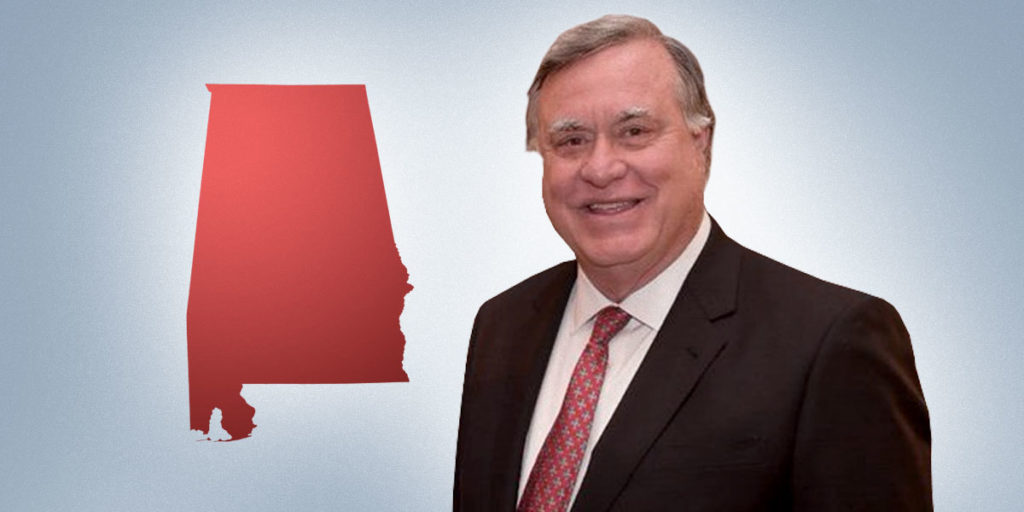

George Wallace Jr. is the son of Alabama Govs. George and Lurleen Wallace. He previously served two terms as Alabama State Treasurer and two terms as a member of the Alabama Public Service Commission.