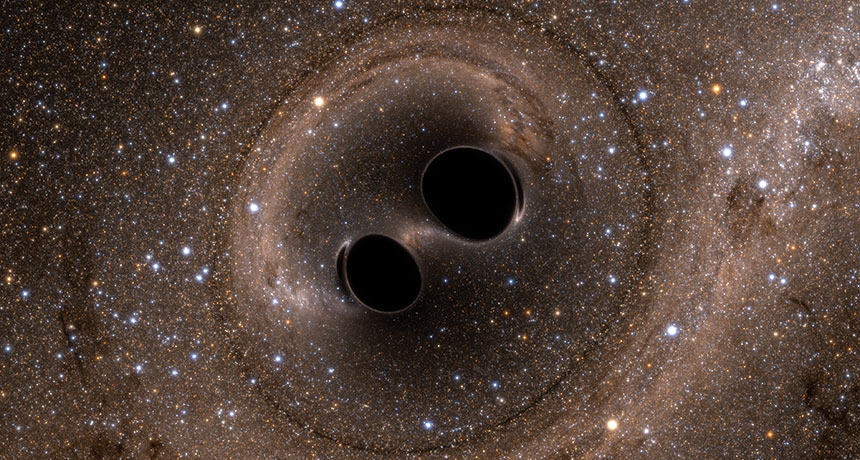

Alabama scientists were instrumental to the confirmation of Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity this week, sending the scientific community into a state of euphoria.

Scientists confirmed the presence of gravitational waves after observing two black holes colliding. This discovery has created global excitement in the scientific community and could change science as we know it.

The waves were recorded as a small beep on two detectors operated by LIGO, short for Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, which is an organization that was created specifically to make this discovery.

Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space-time that Einstein predicted a century ago. This discovery completes his vision of a universe in which space and time are interwoven and dynamic, able to stretch, shrink and jiggle. It also sheds more light on the nature of black holes, which have been a foreboding topic of study for years.

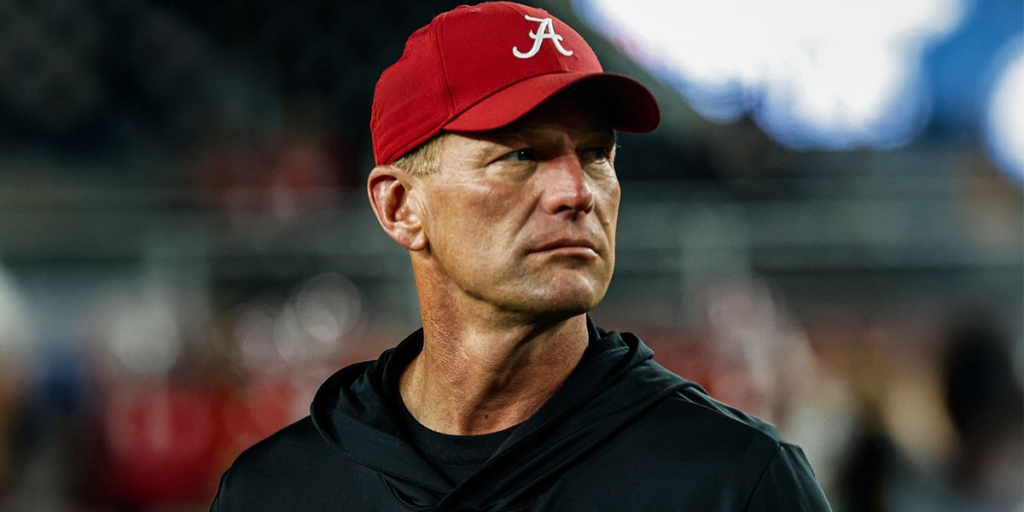

An Alabama researcher and graduate student at the University of Alabama at Huntsville were vital to this discovery. Dr. Tyson Littenberg and his graduate assistant Jessica Page helped LIGO develop the computer algorithms that ultimately confirmed and validated the data scientists had found.

The gravitational waves had been predicted by Einstein’s theory of relativity a hundred years ago, but had never been observed. LIGO’s two detectors, one in Louisiana and one in Washington, made the discovery on September 14, 2015. The waves were produced in “the final fraction of a second of the merger of two black holes to produce a single, more massive spinning black hole,” a UAH news release said.

Littenberg and Page immediately knew that LIGO was finally on to something.

“I knew within a few hours of the detection on Sept. 14 that we had something big. Really big,” Littenberg said in the UAH release. “Two of the data analysis efforts that I work on were right at the center of the action.”

UAH’s Center for Space Plasma and Aeronomic Research (CSPAR) was tasked with analyzing a potentially interesting piece of the data and figure out what the gravitational wave signal actually looked like. The team had to be extremely thorough because of the game-changing nature of this discovery.

“It took months of analysis, re-analysis, checking, rechecking, and re-rechecking of the results before we were ready to say with confidence that we had something, and precisely what we had,” Littenberg said. “The stakes are so high, we tried over and over again to prove ourselves wrong until, exhausted, we admitted defeat and said, ‘This is really it.’”

So what does this discovery actually mean?

“Gravitational waves are the last missing confirmation of Einstein’s general theory of relativity – our most fundamental understanding of how physics works in the macroscopic world,” explained Littenberg.

This discovery has major implications for how we study physics, astrophysics, and astronomy.

Dr. Gary Zank, CSPAR director and chair of the UAH Department of Space Science, said the findings mean “a new spectrum from which to learn new physics.”

“Waves carry information. We use all parts of the electromagnetic spectrum – optical, infrared, ultraviolet, energetic particles – to investigate the distant universe,” Zank said. “Gravitational waves carry information from some of the most energetically violent events in the universe, meaning that we will have a new spectrum from which to learn new physics.”

The confirmation of gravitational waves has been a long time coming.

“LIGO has been working towards this moment for decades,” Littenberg said. “Hundreds of scientists from the world over have dedicated their professional lives to getting this first detection. Hundreds more are hinging their careers on the gamble that gravitational wave detection would pay off.”