Dr. John Christy is among planet Earth’s best known climate scientists. However, being skeptical of today’s claims of a “broken climate” isn’t how he thought he would gain such notoriety when he began his quest for knowledge about climate science at age 10, as he describes in his new book, “Is it getting hotter in Fresno… or not?”

Sixty years later, Christy is a scientist who is vilified by liberal politicians and the left-wing media for his interpretation of the actual data that describes the climate. He understands there is a tremendous amount of “politics” behind climate science, but maintains that the observational data should be our starting point for arriving at conclusions about climate change, no matter what the climate may be doing.

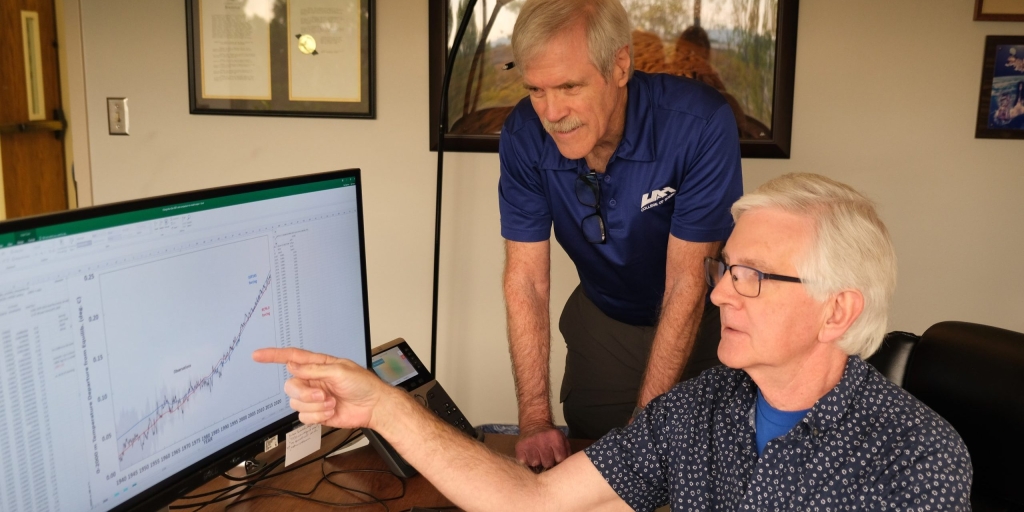

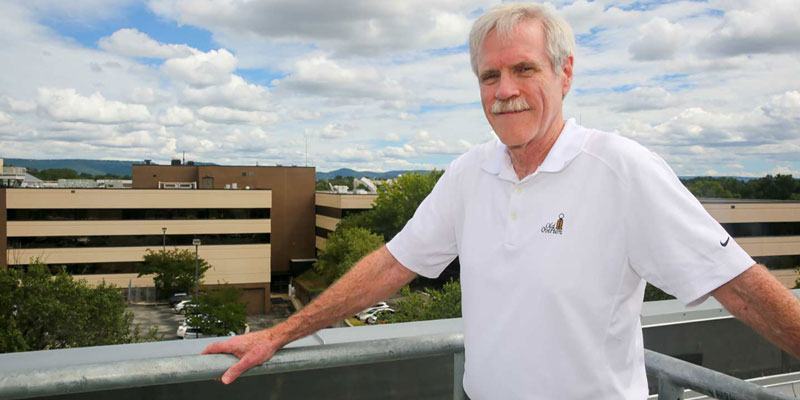

Christy is the distinguished professor of Atmospheric and Earth Sciences and director of the Earth System Science Center at the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH). He is also the Alabama State Climatologist. He has received the American Meteorological Society’s Special Award and the rank of Fellow of this Society for his satellite research. NASA awarded him the Medal for Exceptional Scientific Achievement for work with Dr. Roy Spencer (UAH) on measuring global temperatures from satellites. He has published more than 100 scientific papers and has appeared as an expert witness on climate in U.S. federal court, as well as testified 20 times before the U.S. Congress.

This climate journey is the result of his innate curiosity that began when he was still in elementary school in Fresno, California. He documents that journey with this new book – “Is it hotter in Fresno … or not? A book about my hometown’s changing weather.”

Published by John R. Christy – March 2021)

In the book, he answers the title’s question with a real nuts-and-bolts description of how one builds a climate dataset. But the answer does not fit today’s politically popular narrative. For Fresno, the most dominant impact on temperatures has been a warming due to the massive urbanization around the weather station. This warming is seen in the remarkable rise of nighttime temperatures, while the day time temperatures, where impacts due to extra greenhouse gases should be seen, have hardly changed. So, Fresno’s climate is not broken.

Fresno served as his home from birth to graduation from Fresno State (B.A. Mathematics). After serving as a missionary and teaching physics and chemistry in Kenya, East Africa, he earned a Master of Divinity from Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, then served as a bi-vocational pastor while also teaching math at nearby colleges. He headed back to the classroom for M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Atmospheric Sciences from the University of Illinois. This academic training prepared him for his career at the University of Alabama in Huntsville.

But it was the young inquiring mind of a precocious 10-year-old future scientist to begin climate study in the most unlikely of locations. Indeed, he described Fresno’s “weather-monotony” as the general rule where he spent his first 22 years. He writes the most confounding question to answer at the beginning of this book is, “Why would a curious boy become fascinated in weather and climate while growing up in, of all places, Fresno, California?” Christy says Fresno is not one of those locales about which people say, “If you don’t like the weather, wait around awhile and it will change.”

Christy observed that weather conditions in Fresno were always hot and dry from May to September. Then, during stagnant periods of a week or two between mid-November and mid-February, Fresno would be imprisoned by a gloomy, drizzly “high fog” in which the sun never broke through and the temperature was stuck, miserably, in the mid-30s to mid-40s. He said during this gloom, there was a simple fact that all knew – that just a half-hour’s drive east into the foothills, the warm sun would be shining in full glory. And, if you kept driving another 30 minutes, you would be in the majestically snow-covered Sierra where even there the temperature would be warmer than in the foggy valley.

Christy’s drive to know more about the valley’s weather consumed many hours from the time he was about 10 to his graduation from Fresno State in 1973. But that desire to document and understand the weather of the central San Joaquin Valley has never left him even though after 1973 he would not live in the valley again.

Though writing about the details of building a climate dataset, Dr. Christy also looks at his life as a climate scientist and deals with questions such as: What is the source of the climate data about which so much contention arises? How are these datasets constructed? Are they able to give us precise answers about climate change?

He examines these questions in detail for one spot on the earth – his hometown of Fresno. He delves into the observations, adding some data never before used to build a dataset of temperatures starting in 1887.

Along the way he mentions the personal experiences of his Fresno life that dovetail with his passion for climate science – this to let his grandkids know what type of work he did at the beginning of their century. After putting all of the information together, he arrives at a conclusion that implicates humans for the temperature changes Fresno has seen, but not in the way that is popularly promoted today. He offers finally his insight from his background as a professional climatologist and former resident of Africa as to how we might approach policy decisions regarding this highly contentious issue.

Proceeds from Dr. Christy‘s book will benefit student scholarships at UAH.

Ray Garner is a contributing writer to Yellowhammer News.