While Alabama Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries (WFF) officials continue to do all they can to keep chronic wasting disease (CWD) out of Alabama, unfortunately the latest news from our neighbors in Mississippi is not good.

Another deer in the lower Mississippi Delta in Issaquena County, a 2½-year-old doe, tested positive for CWD last week. The initial CWD case in Mississippi last January was also in Issaquena County, confirmed in a 4½-year-old buck.

These are in addition to the Mississippi deer in a different county that tested positive for CWD about two weeks ago. A 1½-year-old buck tested positive in Pontotoc County in north central Mississippi, about 200 miles from the initial case.

WFF Director Chuck Sykes is watching and analyzing all of these developments very closely.

“These last two cases are concerning,” Sykes said. “Typically, you think of CWD as being found in older age-class males.”

Also gaining Sykes’ full and immediate attention, the Pontotoc County CWD-positive deer was within 50 miles of Alabama’s border.

“With the Pontotoc deer being within the 50-mile radius of Alabama, we’re doing exactly what we said we would do in our response plan,” Sykes said.

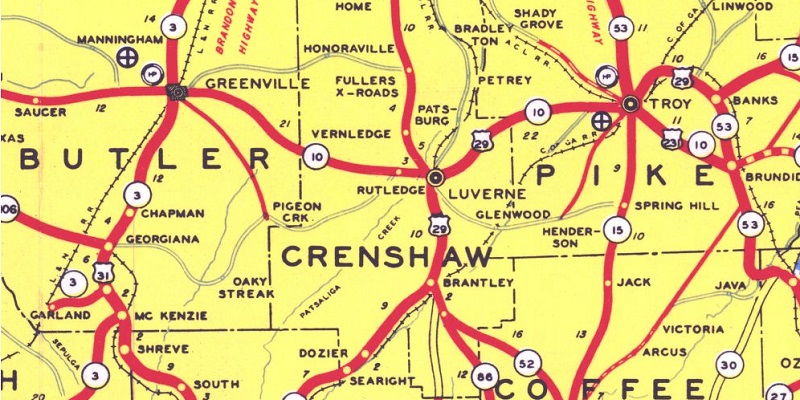

The section of the Alabama CWD Response Plan that deals with out-of-state cases uses concentric circles around the positive test site in increments of 25 miles, 50 miles and more than 50 miles. With the case confirmed in Pontotoc County, portions of three counties in Alabama fall within the 50-mile-radius protocol – Franklin, Marion and Lamar counties.

“We have met with DOT (Alabama Department of Transportation) engineers to help us in locating road-killed deer that will be tested,” Sykes said. “Our technical assistance staff will continue their efforts in working with hunting clubs, taxidermists and meat processors in those counties to collect samples.

“I don’t want people to panic, but they need to understand that we’re doing everything we can to keep it out of Alabama. The main thing I want to get across is that we are not targeting any one particular group. This is not a deer breeder versus a non-breeder. This is not a high fence versus a no fence. This isn’t a dog hunter versus a stalk hunter issue. Honestly, this isn’t even just a hunting issue. This is an Alabama issue concerning the protection of a public-trust natural resource. We really need people to focus on facts about CWD, not what they hear about or read on Facebook.”

Sykes said deer hunting is such a cherished thread that runs through Alabama’s heritage and way of life that any effect on that endeavor could have far-reaching consequences.

“Whether you hunt or not, the economic impacts of deer hunting generate more than $1 billion annually into Alabama,” he said. “In one way, form or fashion, most everybody in the state is positively impacted by deer hunting. So, we’re doing everything we can to keep it out of Alabama.

“In the chance CWD gets here, we have a plan in place to mitigate the risk. It’s all in black and white on outdooralabama.com. What I need the public to know about this is that we have had a CWD response plan in place since 2012. It updates constantly, based on the latest scientific research. I have a whole team that works on this. It’s not done by one person behind closed doors in Montgomery. It’s done on a national level. We look at what works, what doesn’t work, what states have tried and what states have failed–the good, the bad and the ugly. This is a methodical process. Our plan is based on the latest nationwide scientific research.”

Sykes said there is no way to know what will happen in Alabama if CWD is confirmed.

“It’s hard to say how Alabama will be impacted compared to other states,” he said. “Each state is different.”

At a recent Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (SEAFWA) Law Enforcement Chiefs meeting, a conversation between WFF Enforcement Chief Matt Weathers and a member of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission highlighted the vulnerability of Alabama in this situation.

“Northwest Arkansas has a high prevalence rate of CWD,” Sykes said. “Chief Weathers asked his Arkansas counterpart at SEAFWA how CWD was impacting their hunting licenses and budget. In Arkansas it isn’t a major concern because their agency gets one-eighth of 1 percent of sales tax. It does matter to us because we don’t get that. We can’t handle people not deer hunting, not eating deer meat and not buying hunting licenses. It will change the ability of our agency to manage and enhance wildlife and fisheries in Alabama forever.

“I don’t want people to think we are never going to deer-hunt again, that all the deer in the state are going to die. That hasn’t been shown to happen in the CWD-positive states. However, they never go back to the same. We will have to adjust to a new normal. But, we want to prevent it as long as we can. In the event it does come here, we are fully prepared to address it to minimize the risk.”

Alabama has tested more than 8,000 deer during the past 15 years, and no deer has tested positive for CWD.

“We don’t have our heads in the sand,” Sykes said. “We’re doing everything we can. That involves making rules and regulations that are, at times, unpopular. It’s been illegal to bring a live deer into Alabama since the early ’70s. However, we caught someone in 2016 bringing in deer from Indiana for breeding purposes. It’s been illegal to bring a carcass in from a CWD-positive state for three years. This year, we had to ban carcasses from every state. That’s an inconvenience on everybody, us included. A lot of us hunt out of state, so it’s impacting us as well. But it’s something we have to do to protect the natural resources of Alabama because not every state tests for CWD as judiciously as we do.

“We had a joint law enforcement detail with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency along the Tennessee-Alabama state line on Sunday November 11th, checking for illegal carcasses being brought back into Alabama. We made six cases on hunters bringing back field-dressed deer into Alabama from Kansas and Kentucky. In all six arrests, the individuals knew it was illegal to bring the carcass through Alabama. In addition to violating Alabama law, they also violated Tennessee law. Several of the carcasses were destined for Florida, jeopardizing yet another state.”

An old friend, Ronnie “Cuz” Strickland of Mossy Oak camouflage fame, has been directly impacted by the positive CWD test in Pontotoc County, Mississippi. Strickland has a farm in Lee County, Mississippi.

“This is a black cloud, no doubt,” said Strickland, who sits on the Quality Deer Management Association (QDMA) Board. “My farm borders Pontotoc County. We’re just outside the containment zone, but I’m afraid it’s just a matter of time.

“You think that it’s something that’s going on somewhere else, like Colorado, where it started. Or Wisconsin or Wyoming. Then, bam, it’s in the Delta, and now Pontotoc County. It’s happened so fast, it’s kind of scary.”

Strickland said it’s difficult for the average hunter to determine how CWD is going to impact hunting in the South because of the wide range of reactions.

“On one end of the scale, you have people saying the sky is falling,” he said. “On the other end of the scale, depending on who you talk to, they say, ‘Aww, it’s been around for a thousand years.’ I’m assuming it’s somewhere in the middle as to where the truth lies.

“I don’t know if people are taking this as seriously as I have. We’re kind of in the hunting business at Mossy Oak.”

Strickland has been taking his grandson, who has been affectionately nicknamed Cranky, on a variety of hunting adventures in recent years. Strickland doesn’t have any inclination to alter their behavior.

“We’re going to continue to hunt,” Strickland said. “I’m going to assume the people that really attack this and know what they’re doing are going to lead us down the right road.”

Strickland is concerned the CWD threat will have a detrimental effect on the recreational opportunities that have so positively impacted his way of life.

“Hunting license sales are already down,” he said. “This is just another hurdle. We’re battling more than just CWD. We’re battling time, more than anything. The new people, the 30- to 40-year-olds with kids and everything, are having trouble finding time to go hunting. There’s a lot chipping away at our lifestyle.

“Hunting is what we lived for when I was growing up. I used to could sleep like baby the night before Christmas. But the night before hunting season opened, I literally would lie down with my hunting clothes on to make sure I wouldn’t be late.”

David Rainer is an award-winning writer who has covered Alabama’s great outdoors for 25 years. The former outdoors editor at the Mobile Press-Register, he writes for Outdoor Alabama, the website of the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.