When Opelika police officer Benjamin Carswell pulled over Daryl Gray for following too closely in August 2014, Carswell found $32,660 in the vehicle. Gray told Carswell he was on his way to buy a car, but the large amount triggered suspicion.

The officer seized the cash and handed it over to the Drug Enforcement Administration less than a month later. After two months, Daryl Gray filed a complaint in court through his attorney Joe Reed. A local judge ruled a year later that his court couldn’t decide on the case because the federal government kept the cash.

Gray didn’t get his money back and was never charged with a crime.

What happened to Gray is legal under the controversial practice of civil asset forfeiture. Instituted to fight drug crime, it allows police to seize property they have reason to believe was criminally gained – even when the owner isn’t yet charged with a crime – and keep assets with a court order.

Fourteen states require a conviction for forfeiture. In Alabama, state Sen. Arthur Orr and Rep. Arnold Mooney, both Republicans, proposed legislation this year to require a conviction before assets could be seized. The bills ignited three weeks of debate and received so much pushback from police and prosecutors that they were shelved. On Thursday, Mooney introduced a new bill that requires law enforcement to gather detailed data on seized assets starting in 2019 and publish an annual report online beginning 2020. However, it wouldn’t change the current legal process.

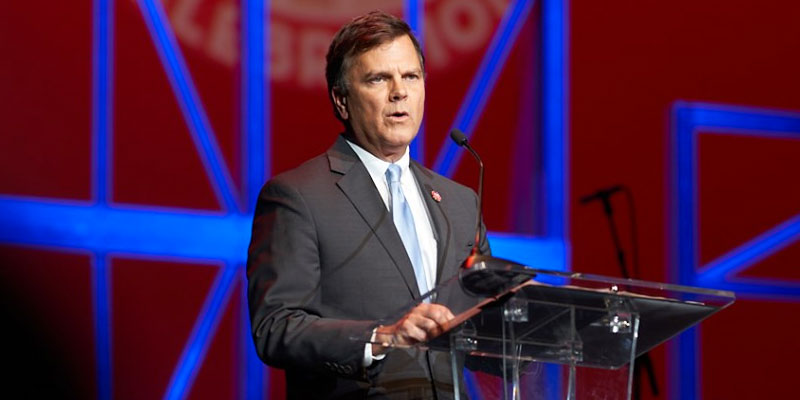

Artur Davis, senior consultant with The Institute for Justice and former U.S. congressman involved in the negotiations, said the bill would move Alabama from being one of the least transparent states to having comprehensive data – although it still falls short of the reforms he and other advocates wanted.

Critics of civil asset forfeiture say it fuels policing for profit because law enforcement gains millions of dollars from individuals not always proven guilty of a crime.

Robert Bradford’s mother fought forfeiture proceedings after her husband faced drug charges and committed suicide in Chilton County in 2009. She proved her innocence and kept her house.

“The problem was that there was no conviction that had taken place, but they were asserting the property belongs to the sheriff’s department. But it’s not the American way at all,” said Bradford, 40, who now lives in the house.

Law enforcement and prosecutors argue civil asset forfeiture is necessary to disempower criminals.

“It’s a tool we have to use to fight crime,” said Clark Morris, a U.S. attorney for the Middle District of Alabama. “It’s not about taking innocent people’s property. It’s about making our communities safe.”

Barry Matson, executive director of the Alabama District Attorneys Association and the Office of Prosecution Services, said that nothing can be seized without a criminal investigation or kept without due legal process under Alabama’s 2014 civil asset forfeiture law. He supported transparency to maintain trust in the police, who have “a strong respect for the property rights of law-abiding citizens.”

But Sara Zampierin, an attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center, said the process burdens the property owner to prove his or her innocence. Judges tend to rule in favor of police, who only have to prove to the court’s “reasonable satisfaction” that assets were criminally gained to keep them.

The law center and Alabama Appleseed, also an advocacy organization, found that property owners were never charged with a crime in a quarter of more than 1,000 civil asset forfeitures in 2015. Although police say forfeiture targets major drug kingpins, the amount of cash was less than $1,000 in around half of the cases. Law enforcement agencies received $2.2 million from state courts and $3.1 million from the federal government in 2015.

Guy Gunter, Opelika city’s attorney, said in a statement that police received around $100,000 forfeited assets over the last three years. The department’s budget is more than $9 million.

Gunter said police complied with federal forfeiture laws in Gray’s case. Gray received a letter from the DEA letting him claim his property in November 2014. He never responded. Gray’s attorney Reed said his client didn’t understand the process until it was too late. An owner must file a claim contesting the forfeiture within 30 days.

At least 80 percent of DEA seizures in the last decade were uncontested, the Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General reported in 2017.

Orr’s and Mooney’s original bills prohibited Alabama state agencies from giving assets directly to the federal government. That was omitted in the new version.

The bill faces a difficult deadline for passage in the two weeks left this legislative session.

(Image: PublicDomainPictures.Net)

(Associated Press, copyright 2018)