I love the game of Monopoly. The hope that I will land on expensive properties first, the poker-esque bluffing, and the art of deal-making with unsuspecting friends makes for a great game night.

Even though I love Monopoly, I don’t always enjoy it. When I’ve missed out on important properties and am mortgaging the few I have left to pay the winner, I’m not having any fun. When it’s obvious I will not win and I slowly move from competitor to benefactor, I’m not thankful and neither are others facing a similar end.

I think this distaste says something obvious: Monopoly is great for the winner. Crowding out competition and increasing prices because you have the power to do so is good sport for the already-powerful, yet detrimental to the mobility of others.

Monopoly is predicated on our tendency towards self-preservation and self-centeredness. This tendency, utilized for recreation in Monopoly, is manifested in Alabama through our occupational licensing laws (also known as permission-slip-to-work laws).

Take locksmiths, for example. Established in the late 1990s, the Alabama Electronic Security Board of Licensure regulates both security alarm installers and locksmiths.

Not a big deal, right?

Wrong. Wrong because Alabama is, as shown in a recent report, one of only 15 states that licenses locksmiths. Wrong because being in such a minority mandates we ask, “Why do we license locksmiths in the first place?”

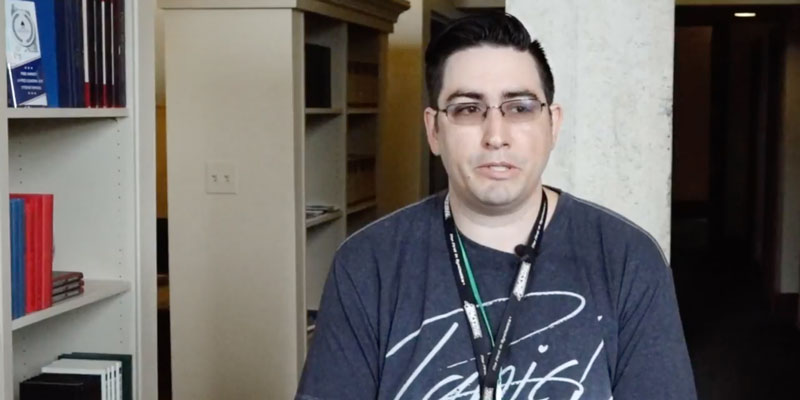

Robert Burns describes his experience as a locksmith in a video recently published by the Alabama Policy Institute. In it, he suggests that the licensing of locksmiths was established in Alabama to protect the power of practitioners – not the safety of the public – and that it makes becoming a locksmith more difficult than necessary.

WATCH:

Before any Alabamian can work as a locksmith they must pay fees, pass tests, and wait to be approved by the government.

In most of the country, these hurdles are nonexistent and residents hoping to work as a locksmith can do so when the private sector (through employers and training), not the government, deems appropriate.

In Alabama, however, tendencies that should be reserved to a board game – tendencies to concentrate power towards ourselves and restrict competition – have been allowed into our occupational licensing structure. We must make every effort, therefore, to identify where licensing exists only to disincentivize entrance into a profession and to eliminate regulations where necessary.

Parker Snider is Manager of Policy Relations for the Alabama Policy Institute, an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to strengthening free enterprise, defending limited government, and championing strong families.