WASHINGTON, D.C. — Last Friday, the U.S Supreme Court agreed to hear a case from California that could eviscerate the power of public sector unions nationwide.

The case, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, challenges the collection of fees that unions use to fund collective bargaining efforts from members who disagree with the group’s political aims. The petitioners, 10 California teachers, along with the Christian Educators Association International, believe that mandatory union payments constitute compelled political speech in violation of the First Amendment.

Although Alabama law prohibits employees of the state from being represented by a union, next year’s decision could have a massive impact on the Yellowhammer state. Large numbers of Alabamians are employed by the Federal Government whose employees are not bound by the same restrictions regarding union representation as their state-level counterparts. In fact, 19.7 percent of Alabamians are employed by some type of government agency.

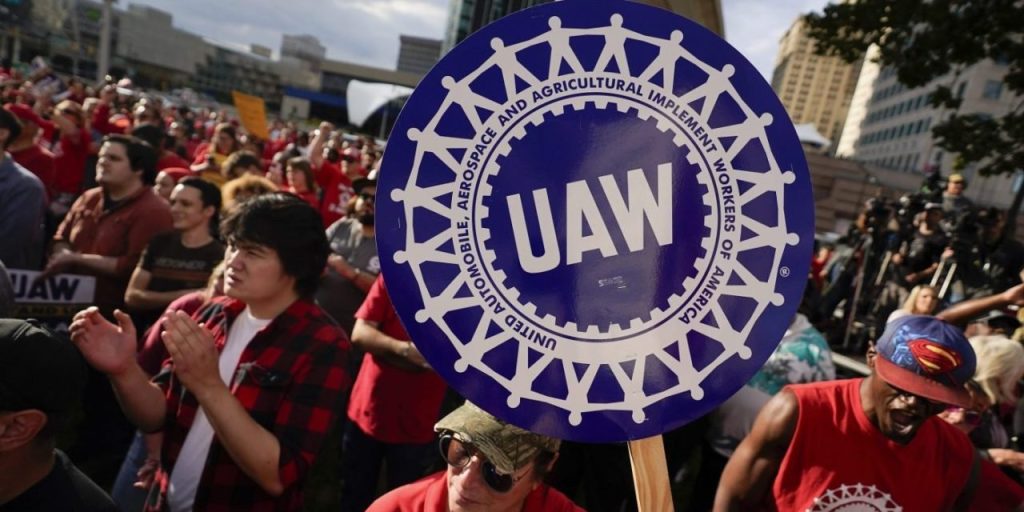

Back in 1976, the Supreme Court heard a very similar case, Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, where union fees were challenged on the basis that they went to unsupported political efforts. The court affirmed that the union shop, which is legal in the private sector, is legal in the public sector. Union shops are arrangements requiring workers to join a particular union and pay dues within a specified period of time after beginning employment; usually 30 to 90 days. Such deals guarantee that workers will pay for the benefits of union representation and avoids the common “free-rider” problem.

The court also found that non-members may be assessed dues for “collective bargaining, contract administration, and grievance adjustment purposes” while insisting that objectors to union membership or policy may not have their dues used for other ideological or political purposes.

But the petitioners in Friedrichs argue that it is the collective bargaining itself that is inherently political. Issues such as teacher tenure and salary have become increasingly politicized and now, they argue, fall within the realm of political speech. The Fair Share agreements are now being challenged, and without them, public sector unions could very well fall apart.

Much has changed in the constitutional interpretation of speech since 1976. The 2011 case Knox v. Service Employees International Union held that by failing to provide a new notice and a new chance to opt out of payment of a special union assessment intended solely for political and ideological expenditures, the union did not abide by the established procedure for handling nonmember payment. In order to respect the First Amendment rights of nonmembers, the special assessment should have come with a notice that allowed nonmembers to opt in.

Furthermore, the 2013 decision in Harris v. Quinn determined that the fair share provision in the collective bargaining agreement between the state of Illinois and the union representative violated the First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and freedom of association of personal assistants who were not members of the union.

The most well-known “union” in Alabama, however, wouldn’t be affected if public-sector unions fall on the wrong side of the high court’s ruling.

The Alabama Education Association, although it walks like a union, talks like a union, and spends like a union, technically does not have the power to collectively bargain and would remain untouched by the court’s constitutional findings. By exploiting loopholes in state law, the AEA does not fall under the umbrella of public-sector unions while still remaining one of the most politically active teachers’ lobbies in the country.

The US Supreme Court will hear Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association in its next term.