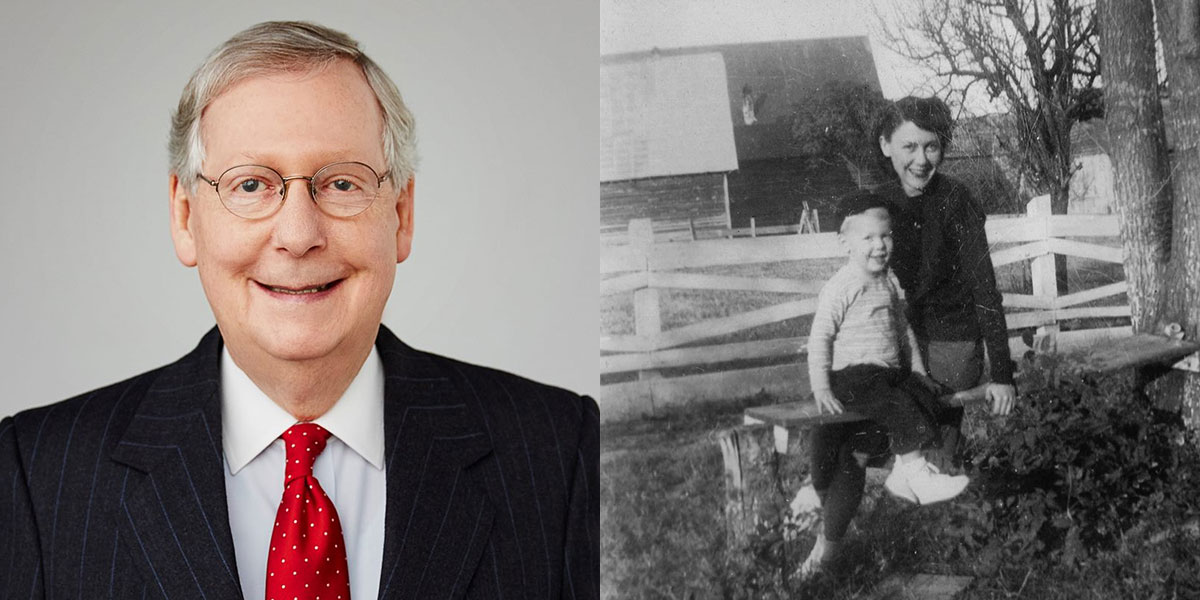

Now serving his 40th year in the United States Senate, Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) has virtually become as synonymous with the Bluegrass State as bourbon and the Kentucky Derby. Still, he would likely concede that the most consequential years of his life played out in Alabama.

Born in Sheffield on February 20, 1942, McConnell spent his first eight years as an Alabamian.

As his father, A.M. “Mac” McConnell II, joined the U.S. Army and deployed to Europe to fight the Nazis, McConnell’s mother, Dean, and her only child moved into a small home in Five Points with her sister and brother-in-law.

In the summer of 1944, a two-year-old “Mitchie” McConnell grew increasingly ill with a burning sensation in his left hand and pain in his legs and lower back. As the sickness grew worse and he began to limp, McConnell’s mother took her young son to visit a doctor just across the state line in LaGrange, Georgia.

It was there that the future senator was diagnosed with a disease that struck fear in the minds of thousands of parents in the 1940s — polio.

“The biggest challenge in my life was contracting polio,” McConnell said in a recent sit-down interview with Yellowhammer News. “This was before the vaccine.”

Fortunately for McConnell, the Warm Springs, Georgia polio treatment facility, often visited by the polio-stricken then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was only an hour’s drive from Five Points, enabling McConnell’s mother to shuttle her son back and forth for weekly examinations.

“We went to Warm Springs, and I was an outpatient there,” McConnell remembered.

For two years, in between visits to the facility, McConnell’s mother kept her son in bed and led him through four rounds of leg exercises each day.

In his 2016 memoir, “The Long Game,” McConnell wrote of his mother, “She was both strict and emboldening, watching me like a hawk to keep me off my feet, and yet reminding me to deeply believe that this was temporary; that one day I would, in fact, walk.”

Within a couple of months after his diagnosis, doctors at Warm Springs noticed that McConnell’s health had steadily begun to improve.

“My first memory in life was the last visit there when I was four,” McConnell told Yellowhammer News, “and I remember them telling my mother that they thought I was going to be able to have a pretty normal childhood and not have a brace, which was their big concern.”

As years went on, McConnell developed a strong interest in baseball and played Little League, but by the time he entered high school, it became evident that he would not have a future in athletics.

“I wasn’t ever very good at running, but I was decent at baseball, but not good enough to make the high school team, and it dawned on me that I needed to focus on something else,” McConnell said.

“So politics became my thing starting in high school, and I’ve basically done it all my life.”

Despite his nearly lifelong love for politics, McConnell is not sure where that particular interest came from.

“I had a great uncle who was a probate judge in Limestone County, but my dad didn’t have a particular interest in politics, so I didn’t really grow up with it,” the Senator said.

“I don’t know where the interest in politics came from, other than when it became clear to me that I was nowhere near the major leagues, I needed to find something else to be good at.”

There is some evidence that McConnell’s ability to thrive in the political arena may be, at least in part, thanks to his childhood battle with polio.

As journalist Michael Tackett notes in his recent biography of McConnell, “The Price of Power: How Mitch McConnell Mastered the Senate, Changed America, and Lost His Party,” polio survivors have been found to have personality traits that geared them toward professional success.

Dr. Richard Bruno, an expert on the aftermath of polio, described survivors as being “hard-driving, time-conscious, competitive, self-denying, perfectionist,” and “overachieving,” several traits that McConnell undoubtedly shares.

Another common phantom of the disease for survivors is post-polio syndrome (PPS), which can be minor or result in a major reemergence of symptoms.

“I may have had a not very serious comeback in this leg,” McConnell said, pointing at his left thigh, “because I do have some difficulty walking, but some people have had a full-scale comeback…But I think I’ve largely avoided that.”

The senator’s weakness in his left leg and trouble walking have, in large part, been the culprit behind recent health concerns.

A fall that left him with a concussion and broken ribs in March of 2023 kept the then-Senate Minority Leader out of the upper chamber for six weeks and has been pointed to as the cause of two incidents in which the senator froze while speaking to members of the press.

McConnell has lost his balance and fallen several other times since that occasion. Still, he keeps a busy schedule and demonstrates an impressive mental command over current policy issues and news of the day.

Throughout his four decades in the Senate, McConnell – the self-dubbed “Third Senator from Alabama” – has gotten to know a handful of Alabama’s senators.

Asked about his thoughts on those who have served alongside him, McConnell said of former Sen. Richard Shelby, “Shelby and I served together for a long time, and he was somebody I could always depend on when I was Leader.”

“I knew Jeff Sessions well,” McConnell continued.

“I think Katie Britt is going to be an all-star.”

“With Tuberville, we talk football,” McConnell, a diehard University of Louisville Cardinals fan, said with a laugh, “and he’s now going to try to run for governor, I gather. I’m probably closer to Katie, but Tuberville and I have a good relationship as well.”

Now eighty-three, McConnell has stepped away from his role in Senate leadership and taken the reins of the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration and the Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense, allowing him to maintain a considerable degree of power without remaining the face of the Republican Conference.

After making history as the Senate’s longest-serving party leader and Kentucky’s longest-serving U.S. senator, McConnell has made his decision not to seek an eighth term public. His tenure is set to come to a close on January 3, 2027.

“I’m in the red zone and heading for the end zone,” McConnell said, making a football reference.

“I was forty-two when I got here, and I’ll be eighty-four when I leave, and I ended up being the longest-serving senate leader in history. I did that for eighteen years until this year. So, this year, I’m much more narrowly focused on defense and foreign policy.”

“And then, wondering what I’m going to do when I leave,” McConnell said, grinning.

Riley McArdle is a contributor for Yellowhammer News. He is a Senior majoring in Political Science at the University of Alabama and currently serves as Chairman of the College Republican Federation of Alabama. You can follow him on X @rileykmcardle.