HACKLEBURG, Alabama – Inside the Wrangler distribution center in this Marion County community, a conveyer system two miles long carries cartons of jeans along a twisting path through the gleaming new facility that has risen from the rubble of April 27, 2011.

Manager Wade Hagedorn walks through the 369,000-square-foot center as workers wearing radio frequency scanners on their wrists place garments in boxes for shipment to destinations throughout the Southeast and beyond. The state-of-the-art facility is a model of efficiency, capable of handling 27 million pairs of jeans a year.

In Hackleburg, the building is also a symbol of regeneration. On that April day three years ago, the deadliest tornado in Alabama history flattened the distribution center that Wrangler had operated on a hilltop here since 1981. Hagedorn and 13 co-workers had taken shelter inside when the EF-5 twister struck, killing one employee and leaving little of the structure standing.

The devastation raised doubts about the facility’s future. Rebuilding the center was not a given for parent company VF Corp., which launched an economic analysis on whether to replace the building or shift its operations elsewhere. Hackleburg, ravaged by the storm that killed 19 residents and wiped out more than 20 of its 32 businesses, held its breath over the fate of its largest employer.

“After all in town were accounted for and the dead buried, the primary question on everyone’s mind became, ‘Could they and would they come back?’” said David Thornell, president of the Northwest Alabama Economic Development Alliance, a regional industry recruiting agency.

State and local officials swung into action to help save the plant. The Hackleburg work force remained loyal, volunteering for a long commute to a temporary shipping facility more than 90 miles away in Cullman County. Alabama Governor Robert Bentley led the charge, pulling together a high-level team and speaking frequently with top VF Corp. officials. An incentives package was assembled.

“You could build a distribution center anywhere in the United States, so why would you build it in Hackleburg, Alabama? I would ask the same question,” Hagedorn mused. “But the end result is that it was our employees.”

Governor Bentley’s involvement was also key, he added.

“I know Governor Bentley was on the phone calling VF CEO Eric Wiseman and telling him how important it was to keep Wrangler in Hackleburg,” Hagedorn said. “So Governor Bentley, to me, was vital in keeping our building in Hackleburg.”

BULL’S EYE FOR AN EF-5

For Hagedorn, the day started with menace.

“On April 27, they were predicting bad weather that day, and actually that morning we had a heavy storm with unusual type hail,” he recalled. “That got everyone’s attention right off the bat. There was a high probability of tornadoes later that day.”

The forecasts were troubling enough that early that afternoon, Hagedorn decided to call off the plant’s second shift, which was scheduled to start at 4 p.m. It was the first time he had taken such a step because of a tornado threat. Tornado warnings were possible for Marion County later that day, and rough weather already had slammed other areas of Alabama.

“I just didn’t have a good feeling about that particular day. I sensed that we needed some extra precaution.”

Hagedorn decided to release the Wrangler plant’s first-shift workers around 2 p.m. Plant personnel tried to communicate to second-shift workers to stay home, but not all the workers got the word.

Fourteen people were in the Hackleburg facility at 3 p.m., when the tornado warning came from the National Weather Service. The plant’s tornado drill protocol called for workers to take shelter in the distribution center’s front office, next to an interior wall.

At 3:25, Hagedorn spotted a worker in the parking lot, retrieving something from his truck. Hagedorn asked Roger Kendrick, a supervisor, to help him get the worker inside. When Kendrick opened the door to urge the worker to come inside, he could hear the tornado rumbling in the distance.

“We didn’t see anything because it was coming from our blind spot. The tornado came, and we went into the office. Roger Kendrick was really the hero. Getting under desks wasn’t protocol, but Roger yelled out, ‘Everyone, get under a desk.’ Nobody asked questions. We just did it.”

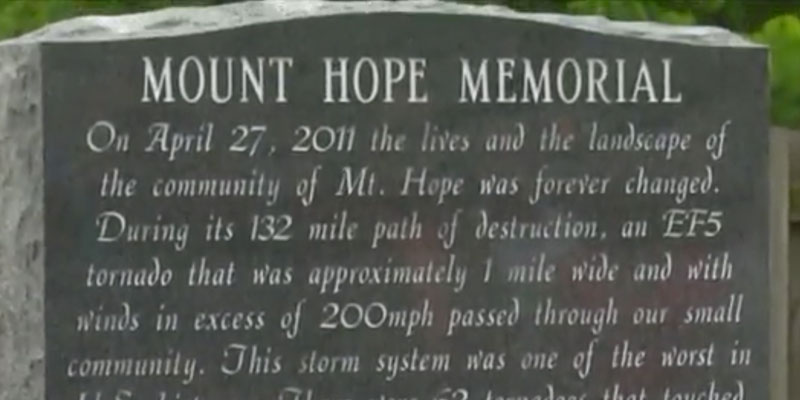

The EF-5 tornado that destroyed the Wrangler plant packed winds that reached 210 mph, according to a National Weather Service report. At its widest point, the tornado stretched more than a mile across. The twister moved next into Franklin County, where it smashed the town of Phil Campbell, and continued on to Tennessee. Its path stretched for 132 miles.

The tornado killed 72 people in Alabama, making it the most deadly twister in state history.

It tore directly into the Wrangler building, tumbling the structure’s large concrete wall panels and tossing about steel rafters. Tractor trailers were knocked over or flung into the rubble. A small mountain of jeans, ripped from their packing cartons, rose at the battered plant site.

Inside the wreckage, Hagedorn had been lucky. Just above the spot where he had taken shelter, the concrete wall slabs had broken apart and fallen to create an upside down V shape over him. He would have been crushed had the panels simply tumbled over, as many had.

“Within 10 seconds of when we felt like it was hitting, it was over,” he recalled. “We didn’t know the extent of the damage. We knew it was bad. But we didn’t know how bad until we got out.”

Hagedorn said an impromptu roll call started while the Wrangler workers were still trapped under the desks.

“Nobody could see each other, but we kept hollering out, going down the line. You could hear it coming down the line: ‘You there? You there? You there?’ Everybody knew who was next to them. Right off the bat, we knew we were missing one. We knew right from the very start that someone wasn’t answering.”

Linda Knight, who had 32 years of service with Wrangler, was killed when the building came down.

The survivors crawled out to scenes of destruction.

“It appeared that the building had been chewed up and spit out,” Thornell recalled. “Left behind was an indistinguishable pile that reached close to 30 feet high across the huge slab. Jeans took flight and were found as far as 90 miles away.”

THE RECOVERY BEGINS

In the aftermath of the storm, Greensboro, North Carolina-based VF Corp. delivered computers and cell phones to assist in the recovery effort, and it ordered new uniforms for first responders. The company sent in truckloads of supplies, including water, flashlights, batteries and power generations.

“Within 24 hours, we had a trailer full of supplies sitting here,” Hagdorn said.

The distribution center workers began meeting at the company’s old Hackleburg sewing plant, which transformed into a gathering place for the healing process to begin, Hagedorn said. It would later become a temporary shipping facility. Before long, most of the workers were making the long trek to Holly Pond in Cullman County, the site of a second temporary shipping facility.

In May 2011, VF Corp. said it would make announcement about the Hackleburg location in 60 days, but the analysis dragged on. The announcement finally came on Aug. 1, and the news was what all of Hackleburg’s 1,500 residents had longed to hear.

“The Wrangler plant and our employees are the economic base in Hackleburg. We have small companies and other businesses, but this is really the mainstay of Hackleburg,” Hagedorn said.

In VF Corp.’s announcement, CEO Wiseman said the decision hinged on “multiple factors,” notably “a workforce who has demonstrated a passion for their work and a commitment to our company.” Wiseman also acknowledged the “support and assistance” provided by Alabama officials during the assessment.

“Governor Bentley recognized that the impact of having Wrangler back in Hackleburg would be greater to the small town that was almost gone with the wind than in most other places where new businesses are welcomed but not quite so desperately needed,” said Thornell, the head of C3 of Northwest Alabama.

Just days after the tornado, Governor Bentley assembled a task force of representatives from cabinet-level agencies to examine every possible avenue to save Hackleburg’s largest employer, said Jim Byard Jr., director of the Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs. Utilities companies and others joined in to help. Local officials were part of the push.

“It was truly a team effort,” Byard said. “The governor played a lead role.”

A groundbreaking ceremony for the new facility was held at the site in Hackleburg on April 27, 2012, the first anniversary of the tornado strike. On the same date in 2013, the ribbon-cutting ceremony took place at the new Wrangler distribution center. This year, to mark the third anniversary, the plant had a family day cookout, along with a remembrance for the storm’s victims.

The new facility, built on the footprint of the old structure, was designed with expansion in mind, and an increase in the workforce. The new Wrangler distribution center reflects optimism in the Hackleburg community, where the rebuilding continues.

“It’s a brand new building – it’s a great thing,” Hagedorn said.

This post originally appeared on the Made in Alabama blog.