Nobody likes paying taxes. Accepting inevitability can make paying less painful; Benjamin Franklin observed that only death and taxes were certain in life. Or perhaps Oliver Wendell Holmes’ observation that taxes are the price we pay for civilization might console us. But the handing of sales tax revenue back to retailers may rekindle anger over taxes.

Rebating revenue compensates retailers for the cost of serving as the tax collector and goes back to the 1930s, when states first imposed sales taxes. Collection costs were significant, especially before computerized cash registers. Not all states compensated retailers, and some allowed only a modest annual rebate.

Sales tax refunds have now become one of the incentives state and local governments use for economic development. Governments for years have offered tax exemptions, regulatory relief, and targeted spending to businesses relocating or expanding in their jurisdiction. Just last week, Toyota and Mazda announced they would build an assembly plant in Huntsville, while gun maker Kimber announced a plant in Troy. Incentives factored in both deals.

Other taxes get diverted to business interests. The city of Troy in 2017 considered a surcharge on movie tickets that would be refunded to theater operators; other cities already do this. Property tax revenues can be exclusively used to benefit a selected neighborhood through a tax increment financing district.

I do not wish to debate development incentives today. Rather, I wish to consider the subterfuge involved with tax diversions.

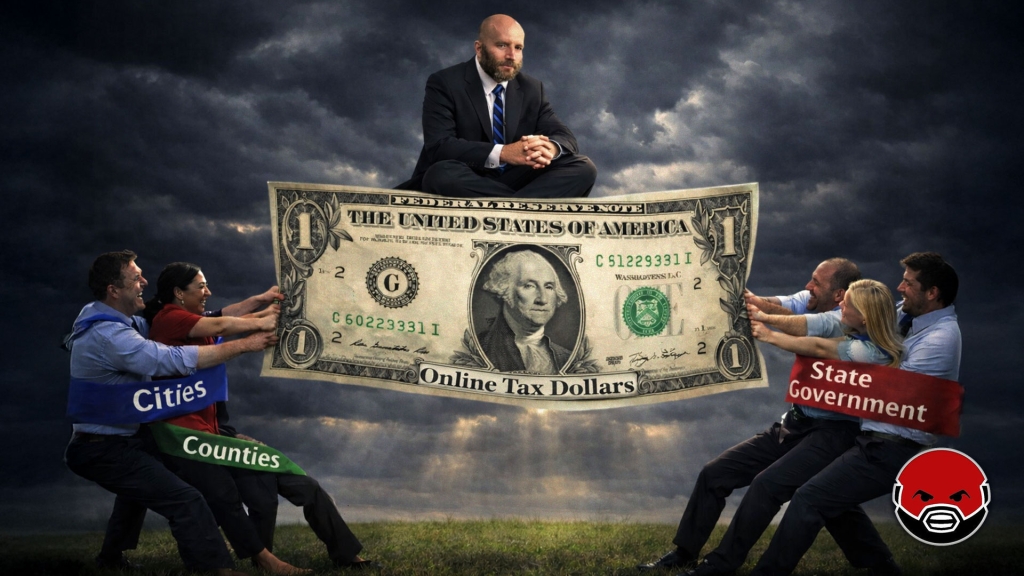

How much sales tax revenue gets diverted? The only systematic study appears to be a 2008 report by government business incentives watchdog Good Jobs First. “Skimming the Sales Tax” estimated diversion of $1 billion annually, with over $70 million of this total going to Wal-Mart. With the use of incentives increasing, the number is almost certainly bigger today.

Compensating for collection costs seems reasonable but debatable, since businesses do not get compensation for collecting payroll taxes. Refunds as incentives are more problematic, for two reasons.

First, deception undermines the legitimacy of taxes. Libertarians like to say that taxation is theft, and there is a resemblance. Theft involves armed people forcibly taking money or property from people. Ultimately taxes rely on tax evaders facing arrest or seizure of their property.

The consent of citizens distinguishes taxation from theft. We agree to pay sales (and other) taxes to provide government the resources to do what we ask. The sales tax funding of a new jail here in Pike County provides a perfect example. Of course our elected representatives make the decisions for us and representation is imperfect, but in principle we approve taxes. Do you approve of turning over sales tax revenues to retailers?

Second, using tax rebates as a stimulus encourages excessive use of incentives for businesses. There are reasons for and against offering inducements to businesses, and people will disagree about how these balance out. Democracy is about citizens deliberating, and decisions which reflect our judgments.

Obscuring part of the cost through tax rebates increases the difficulty for citizens in accurately assessing incentives’ net value. We easily see the benefit from a new retail store, but may fail to process the lost tax revenue from rebates. We consequently think that inducements offer better value than they do, and then provide them too often.

Confusion over tax diversion can make local governments appear ineffective. Suppose that a local government is funded by a 5 percent local sales tax, which we think should adequately fund its services. Yet if half of the revenue gets refunded, the local government might not have enough money to patch potholes. We hit a pothole and accuse government of wasting our money, instead of recognizing the pothole as a cost of development incentives.

Taxation is not theft as long as we decide how much we pay and what we pay for. Refunding sales taxes to retailers as an incentive may be good policy for state and local governments. But it should be policy only if we make a fully informed decision.

Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University.