Nick Saban will turn 65 this year, just days before Alabama travels to Baton Rouge to take on SEC West rival LSU in Death Valley. The Crimson Tide will be eight games into the season by then, and either on their way to once again meeting the perennial high expectations that come with being the most successful college football program in modern history, or out of the title hunt after suffering an early upset defeat.

Regardless of the Tide’s record at that point in the season, Alabama fans can rest assured that Saban will be laser-focused on the task at hand. That’s what his famed “process” is all about, after all. But it hasn’t always been that way. As a young head coach at Michigan State in the mid-1990s, Saban was far more affected by, well, everything — especially outside expectations.

“The last couple of years at Michigan State I had a philosophical change in my approach,” an introspective Saban recalls in a lengthy sit down with ESPN. “I was all about winning. There was pressure on me. I felt like I had to win, like I had to prove myself all the time. And sometimes I felt like I affected the team and made them feel that way. When I went to LSU, I adopted the philosophy that we’re going to play one play at a time, like it has a history and a life of its own, and we’re going to dominate the competition. It was more fun for me, more fun for the players and we got better results.”

Five National Championships and two National Coach of the Year awards later, Saban is dealing with an entirely different set of problems. He is no longer clawing his way to the top. Instead, he’s trying to beat back the current versions of his younger self, who want nothing more than to knock him off of his lofty pedestal.

Marcus Aurelius, the last of Rome’s so called “Five Good Emperors,” could relate. He overcome the Parthians, Germanic Tribes and countless other enemies on the battlefield, and even squashed a rebellion led by one of his most trusted generals (looking at you, Kirby Smart). Through it all Aurelius earned a reputation for being indifferent to external events, whether good or bad.

“You have power over your mind–not outside events,” Aurelius wrote in “Meditations,” today a classic in Stoic Philosophy. “Realize this, and you will find strength.”

“Even 2,000 years ago, Marcus Aurelius was talking about ‘The Process,’” Saban observes. “If you’re going to have goals and achieve those goals, then you’re going to have to overcome obstacles. Those obstacles don’t impede you. They make you better.”

With that approach, Saban seems to have mastered the well-known duck metaphor: calm on the surface, paddling furiously below the surface.

After winning the 2016 College Football Playoff National Championship, Saban took a 90-minute nap on the plane home from Glendale, Arizona, then woke up and immediately went back to work dissecting the game film.

“My dad was a perfectionist,” he says, explaining where he acquired his nearly superhuman work ethic. “He had high expectations for not just how we played football or baseball. He had high expectations for how we treated other people, high expectations for what kind of compassion we had for other people, how we helped other people. When I washed a car and it had streaks on the side, he said, ‘Wash it again.’ So I kind of grew up learning that if you didn’t do it right, there were going to be consequences that you had to deal with. And it was much easier doing it the right way the first time.”

But sometimes Saban’s compassionate streak and his belief that wrong actions should have consequences come in conflict with one another. In those cases, especially with regard to his players, compassion often wins out.

“Guy makes a mistake, where do you want them to be?” Saban asks. “Want them to be in the street, or do you want them to be here graduating?”

In one notable example, Saban points to former Michigan State and NFL wide receiver Muhsin Muhammad, a player he coached while in East Lansing. Saban said the media was “killing the guy” because he got into trouble. He suspended Muhammad, rather than kicking him off the team, and Muhammad eventually went on to graduate from Michigan State and play 15 seasons in the NFL. He is now the managing partner at Axum Capital Partners, has seven kids, and his oldest daughter goes to Princeton.

“So my question to you is, where do you want them to be? You want to condemn them to a life sentence, or do you want a guy to have his children going to Princeton?”

As Saban prepares for the 2016-2017 season’s opening game against USC, he’s urging his team to focus on a familiar enemy that often accompanies success: complacency.

“Complacency [is the greatest threat to excellence],” Saban warns, “being satisfied with where you are. Complacency creates a blatant disregard for doing what’s right. You can’t do what you feel like doing. You’ve got to choose to do the things that are going to help you accomplish the goals you have. When you get complacent, you lose respect for winning.”

In an effort to fight off the urge to be content with past successes, Saban has built a culture in his program that develops leaders at all levels.

“We have a high standard for what we want to do with our players,” he explains. “Leadership comes from the power of one. You affect one person by the example you set, being somebody that somebody can emulate, caring about somebody. And then you affect two more guys and then three more guys. Then the next thing you know everybody’s kind of affecting everybody in a positive way.”

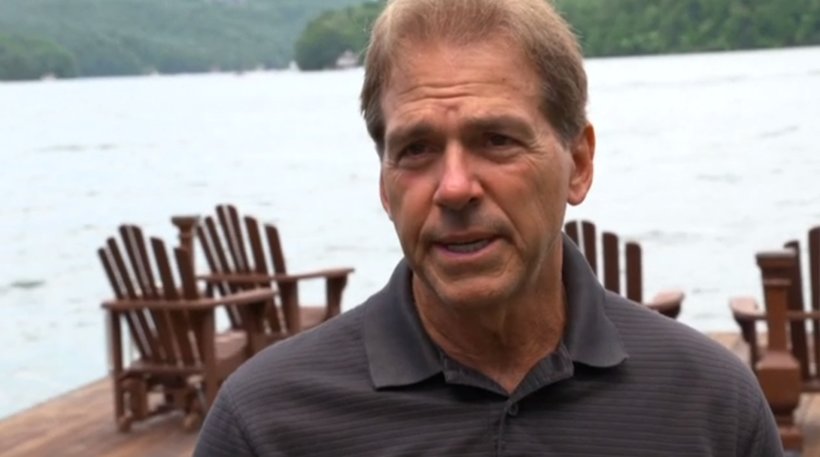

But even though Saban says he spends the vast majority of his time “thinking about the next challenge,” rather than dwelling on the last, he does take time away from the game, usually on Georgia’s Lake Burton.

His children have told him to “never sell the lake house,” not only because it has become his solace from the storm, but because of the memories they’ve built together in the coach’s all-too-brief respites from work.

“If there’s anything I’d like to tell everybody out there, it’s that we’re all so worried about getting ahead, and how many games we’re going to win and all that, but when you get my age and at this station, you look back and think, ‘Well, why didn’t we spend a little more time doing that?’ And ‘why didn’t we film that?’ And ‘how can we capture that?’ Because you can’t relive it. As you get older, you realize some things are more important than when you’re coming up and trying to make it and you didn’t value the memories as much as you do now.”

Saban’s philosophy on coaching has changed and developed over the years, but perhaps not nearly as much as his philosophy on life. In a statement that may illustrate this best, the famously unsatisfied coach offers one piece of advice above all others:

“For everybody out there,” he concludes, “you’ve got to enjoy the moment.”

(h/t ESPN)