Our world has changed almost unimaginably recently. The cancellation of the NCAA basketball championships brought us, in my son’s words, “March Sadness.” Why has our nation responded so dramatically and differently to COVID-19 than earlier pandemics, including H1N1 just 11 years ago? Economics offers a couple insights.

Things are certainly different. In 1919, hockey’s Stanley Cup was canceled due to the Spanish Flu. Not weeks ahead, however, but hours before Montreal and Seattle were to play Game 6. Montreal’s coach and five players had the flu; star Joe Hall died just days later.

The last global pandemic was H1N1. Schools and colleges remained open, and sports and entertainment did not halt. I remember the pandemic’s start and how the danger never seemingly materialized, but that wasn’t entirely accurate. The CDC estimates that the U.S. experienced 13,000 deaths, 275,000 hospitalizations, and 60 million cases; worldwide deaths may have exceeded 500,000.

Sports leagues certainly made no effort to soldier through COVID-19. Why the change? For one, we are wealthier than ever, and safety is a luxury good. In economics, a luxury good is one where its percentage of consumer spending increases as income goes up. Items like jewelry and vacation travel fit this description.

I use safety here because dozens of choices we make create risks to our life and health. Travel, diet and exercise, leisure activities, and work all matter. As people get richer, they are less willing in these choices to put themselves and their families at risk. Differences in attitudes toward risk can obscure this. Some rich people enjoy dangerous activities like skiing and flying a plane, while not all hypochondriacs are wealthy.

Because safety is a luxury, our actions during a pandemic will change. I would not expect a sports league to play until the players were dying, and we will close schools and cancel festivals more quickly than before. Furthermore, our greater knowledge of diseases affects our choices. Death tolls that were “acceptable” in the past are no longer so.

But more than just changing preferences are at work here. The economics of capacity constraints also matter.

We live in a world of scarcity, so we cannot get everything we want. We must produce the goods and services we value with limited resources. Production takes time and uses tools like factories, assembly lines and bulldozers which themselves take time to make. We cannot ramp up production as quickly as we might want.

The capacity constraints for COVID-19 are in the health care system: hospital beds, beds in intensive care units, ventilators, and supplies of drugs and antibiotics. According to the American Hospital Association, there are 925,000 staffed beds nationwide, with about 100,000 in intensive care. We might wish we had more beds, but capacity is costly; imagine maintaining hospitals solely for use in a pandemic.

This is why social distancing, canceling sporting events and festivals, and working from home are so important. Epidemiologists refer to this as leveling the curve, meaning the curve you get when plotting the number of new cases per day. In a pandemic, this curve can grow fast; enough growth in cases will overwhelm any capacity constraint.

Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel recently said that two out of three Germans may get COVID-19. Let’s suppose that proportion applies here. The timing of the cases determines whether capacity will be exceeded. If they occur over one or two years as opposed to one or two months, every patient who develops pneumonia can get the very best care possible today.

The dynamics are in a way similar to the seasonal flu. Healthy young adults face little risk from the flu. A flu shot helps them relatively little, but can keep them from giving their grandparents the flu. We would be wise not to be excessively brave in the face of what for some of us might be little danger.

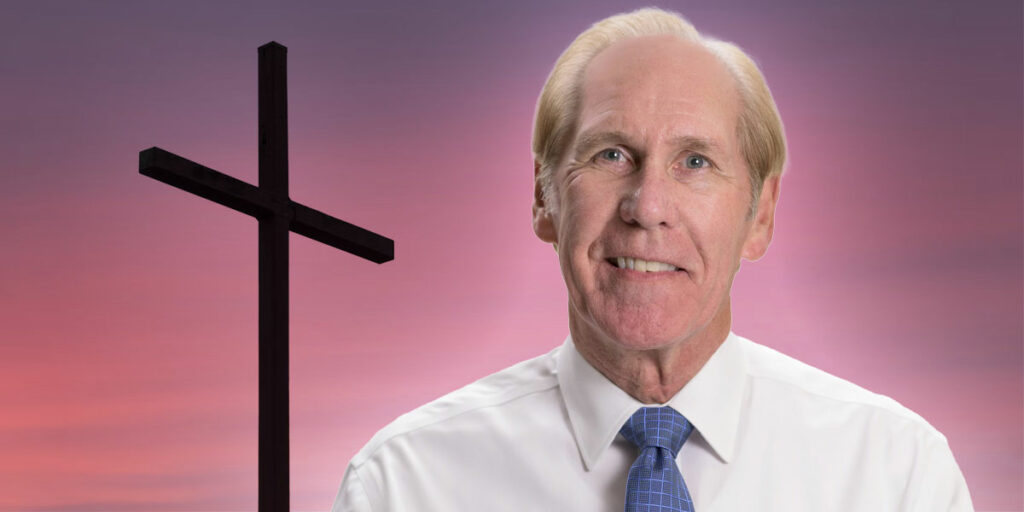

Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.