Glenn Fleisig, Ph.D., an alumnus and adjunct faculty member of the School of Engineering, has done pioneering research that is making baseball safer for Major Leaguers, and Little Leaguers.

As the epic 2016 World Series between the Cubs and the Indians wore on, there was one question on everyone’s mind: When will Aroldis Chapman’s arm wear out? (The answer: Game 7, 8th inning.)

When sports biomechanics expert Glenn Fleisig, Ph.D., an adjunct professor in the UAB School of Engineering and graduate of the school’s doctoral program in biomedical engineering, looks at fire-throwing pitchers like the Cubs closer, he sees a more fundamental problem: How can any human throw 100 miles per hour without his arm falling off?

Fleisig, the director of research at Birmingham’s American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI), answered that question during a standing-room-only lecture at UAB’s Heritage Hall as part of the weekly lecture series hosted by the Department of Biomedical Engineering. Fleisig also encouraged the crowd of undergraduates to investigate the growing field of sports biomechanics research.

Ligaments strike out

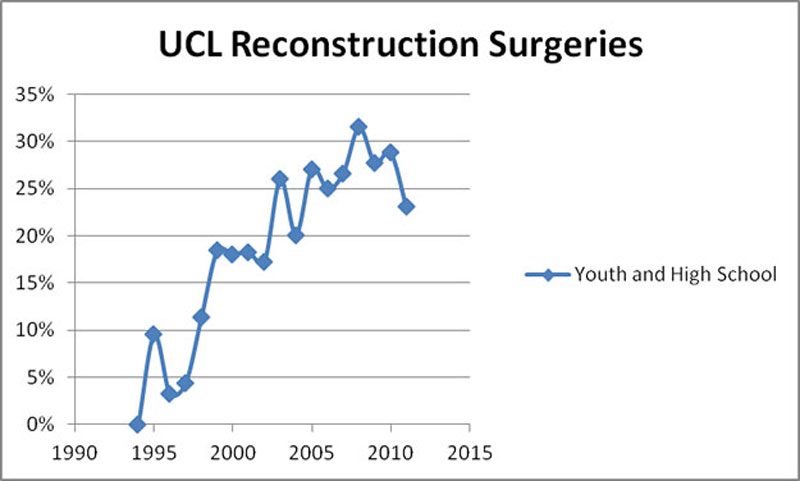

“Baseball is in general a safe sport,” said Fleisig. Except, that is, for pitchers. As Fleisig pointed out, more than one-quarter of current Major League pitchers have already had a major elbow surgery known as “Tommy John surgery.” For decades, Fleisig has studied pitchers at all levels of the game, from Little League to the Major Leagues, compiling detailed biomechanical analysis on thousands of players in the ASMI database. He is a member of the Major League Baseball Elbow Task Force, a research collaboration established to find out what’s behind the epidemic of Tommy John surgeries among professional and amateur players. (See chart below.)

Tommy John, a pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers, tore his ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) in 1974 and was the recipient of an experimental UCL reconstruction surgery by Dodgers team doctor Frank Jobe, M.D. (Fleisig noted that Jobe had been pondering the problem of UCL reconstruction since a torn ligament ended the career of Dodger legend Sandy Koufax a few years earlier.)

The surgery, and John’s successful post-surgery career, made the procedure standard practice. Still, “there were only about 5–10 Tommy John surgeries per year among professional (Major League and minor league) pitchers for 20 years,” Fleisig said. “And then it started going up and up. Then a year or two ago it went way up, to 100 per year or so.” As Fleisig pointed out, more big leaguers had the surgery in 2014 than in the all of the 1990s combined. This increase was obviously troubling to Major League teams. Despite the historic success of the surgery, and post-Tommy John careers for most pitchers, some 20 percent of players don’t return to their old level after the operation. And the increase in UCL reconstruction surgeries among youth and high school athletes was perhaps even more concerning.

Arms race

Fleisig and James Andrews, M.D., the noted sports surgeon who is a founder of the American Sports Medicine Institute, have led several studies looking into the problem. That includes long-term research following hundreds of youth and professional players, along with cadaver studies investigating the biomechanics of the joints and tissues involved. “We have data from testing of more than 2,000 pitchers at ASMI, including an elite database of more than 100 professional pitchers who throw greater than 87 miles per hour during testing,” Fleisig said.

Using a high-speed, three-dimensional, automated motion analysis system, the researchers computed kinematics (motions) and kinetics (joint forces and torques) to gauge the stress on the crucial elbow and shoulder joints during a pitch. During a critical instant when the arm is cocked back, the stress on a major leaguer’s elbow is 100 Newton-meters. He illustrated the concept with an analogy and a visual image: “That’s the equivalent of having five 12-pound bowling balls pulling down on your arm,” he said. “It makes sense that this ligament is near its maximum on every pitch.”

Beginning in spring 1999, Fleisig and Andrews followed 476 youth pitchers, tracking their innings pitched and injuries over a full season. “Then we called these same kids every year for 10 years,” Fleisig said. In a 2011 paper, they published the results, showing that athletes who pitched more than 100 innings per year had more than triple the risk of arm injury compared with those who pitched less than that threshold.

TMP + PM = TJ

Fleisig summarized the results of all that research in a single slide. There are two main risk factors for baseball arm injuries, he said:

• Too much pitching

• Poor mechanics.

“This isn’t just a Major League problem, or a Little League problem, but a baseball problem,” Fleisig said. “So the solution has to be at all levels, too.” The ASMI research has had a significant impact, with numerous leagues adopting pitch limits for players. The Elbow Task Force also developed a website with Major League Baseball, called Pitch Smart, that summarizes its findings for coaches and players of all levels. The site includes detailed pitch counts and rest recommendations for players at various age levels. It also includes a step-by-step guide to proper mechanics.

That type of translational research, which is helping thousands of young athletes avoid injury and surgery, and improve the game he loves, is thrilling, Fleisig said. “Biomechanics is big and exciting and fun.”

He also welcomed any interested students to apply for internships at ASMI, noting its location just down University Boulevard from UAB. “You can tie in motion studies and cadaver studies and more to solve problems that are important to real people.”