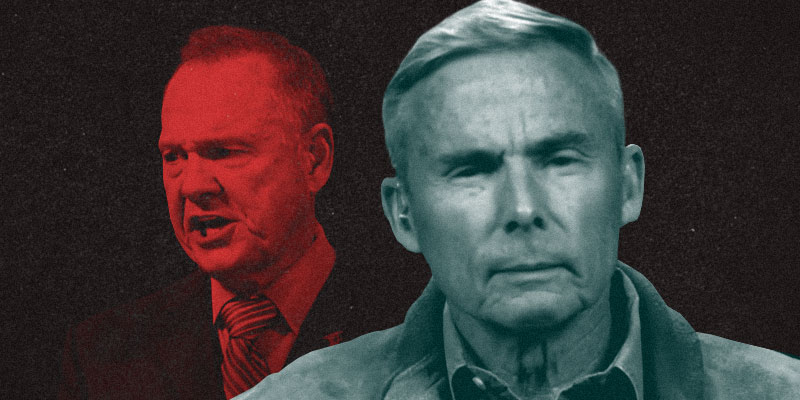

Roy Moore is not in the Supreme Court chambers today as the justices weigh whether a Colorado baker had the right to say “no” to a gay couple, but the Alabama Senate candidate’s fingerprints will be on the debate, nonetheless.

The former Alabama Supreme Court chief justice’s private legal group, the Foundation for Moral Law, filed one of the nearly 100 “friend-of-the-court” briefs on behalf of organizations and individuals arguing for or against Masterpiece Cakeshop and owner Jack Phillips.

The plaintiffs argue that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission violated their First Amendment rights by declaring that they unlawfully discriminated against Charlie Craig and David Mullins when Phillips refused to make a custom wedding cake for them in 2012 — before same-sex marriage even was legal in the state.

It is precisely the kind of issue that prompted Moore to create the foundation, which has come under scrutiny during his run for the Senate seat once held by Attorney General Jeff Sessions. His opponents have accused him of using the foundation as a vehicle to enrich himself and his family.

On perhaps no other issue has Moore been more outspoken than same-sex marriage, however. His uncompromising stance has won him loyal supporters, but it also has brought him fierce critics and jeopardized his career.

It was Moore’s instructions to probate judges to follow state law on same-sex marriage — rather than federal judicial orders — that led to his suspension as the state’s top justice.

The arguments in the foundation’s 28-page brief filed earlier this year mirror those of Phillips’ lawyers and many of the organizations that have weighed in on his behalf. Religious freedom and free speech together form a “hybrid right” that should be afforded the strongest of protections by the government, attorney John Eidsmoe wrote.

“Those most fundamental rights should not be abridged to accommodate a claimed state interest in protecting same-sex marriage which is not explicitly granted by any provision of the Constitution and which was first recognized by this Court only two years ago,” he wrote.

Eidsmoe also makes some arguments that the plaintiffs’ lawyers do not mention, such as that compelling Phillips to create a custom wedding cake violates the 13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery. The amendment did not just abolish the slavery system but also outlawed “involuntary servitude.” Eidsmoe pointed to a 1988 Supreme Court case called United States v. Kizminski, which defined involuntary servitude as work “enforced by the use or threatened use of physical or legal coercion.”

Moore’s position puts him on the same side as the state of Alabama, which signed on to a separate brief with 18 other states plus Maine Gov. Paul LePage. It argued Colorado’s position is “fundamentally at odds with the freedom of expression and tolerance for a diversity of viewpoints.”

The states argued that there are “a host of alternatives for promoting the availability of customized artistic works at same-sex weddings. For example, States can create online tools publicizing those artists who will create works celebrating same-sex weddings.”

The Colorado Civil Rights Commission and the gay couple argue that the case has nothing to do with free speech or religious freedom. Instead, they maintain, it is about a long-established concept of “public accommodations.” No business open to the public may turn away customers on the basis of race, sex or other personal characteristics.

But Eidsmoe, in a brief quoting James Madison and making references to the Bible, noted that Phillips never refused to let a gay customer buy a product for sale in the store.

“He merely objected, because of his religious and moral convictions, to participating in the ceremony by preparing a customized wedding cake,” he wrote.

Eidsmoe’s brief argues that the Colorado Court of Appeals “twisted the newly-minted right to same-sex marriage into an imaginary right of same-sex couples to force others to promote their same-sex weddings.”

Eidsmoe outlined America’s long history of accommodating the views of religious minorities. He referenced a Supreme Court decision in which the high court ruled 8-1 in favor of a Jehovah’s Witness who was fired from his job after refusing to build tank turrets because it would violate his pacifist religious beliefs.

When considering whether a religious belief is valid, the brief argues, the court must defer to the practitioner.

“Phillips bases his beliefs and practices on the commands of God as revealed through the Holy Bible (e.g., Leviticus 18:22; Romans 1:26-27),” the brief states. “He believes he would sin against God if he were to provide a cake for a homosexual wedding.”

Brendan Kirby is senior political reporter at LifeZette.com and a Yellowhammer contributor. He also is the author of “Wicked Mobile.” Follow him on Twitter.