No one really knows how the game is played

The art of the trade

How the sausage gets made

We just assume that it happens

But no one else is in

The room where it happens

This description of 1790s American politics in the well-known musical Hamilton echoes a still-relevant sentiment–that regular Americans really don’t know how all of this happens.

But is that feeling accurate? Looking at our inability to pass a federal budget, the process of choosing Supreme Court nominees, and even our own recently-increased gas tax, it’s hard to say it’s not. Often it feels like we don’t know how any of this really gets decided (and that attempts to find out would be futile).

Soon enough Alabama will be dealing with another potential “room-where-it-happens” scenario, one that will have lasting impacts for residents across the state.

The scenario? Redistricting–the process of redrawing state and congressional legislative district lines.

Unfortunately, in some states the definition might more accurately be “the power of legislators to decide who they want to represent and who they want to get off their backs.”

One state where that definition has proven true is Illinois. And you need not look further than the story of President Barack Obama for confirmation.

In 2001, when the Illinois state legislature was drawing new district lines (a requirement after every census), then-State Senator Barack Obama made a decision. Set on higher office, Mr. Obama had already run and lost a congressional race in a heavily poor, heavily African-American district. He needed a stronger base. In a shrewd political move, Mr. Obama calculated that he would benefit from a district with more affluent and higher educated residents who might better identify with an academic from the University of Chicago.

As a member of the state legislature, Mr. Obama was able to draw the new lines to his exact needs. His revamped district was still majority African-American in makeup, but it now included many of the wealthiest neighborhoods of Chicago. It was this richer, more-connected demographic that Mr. Obama leveraged to launch and fund his successful campaign for U.S. Senate in 2004 and, from there, his bid for the presidency.

Now that’s Illinois. Is Alabama just as bad?

The short answer to that question is that – if residents don’t pay attention – it could be.

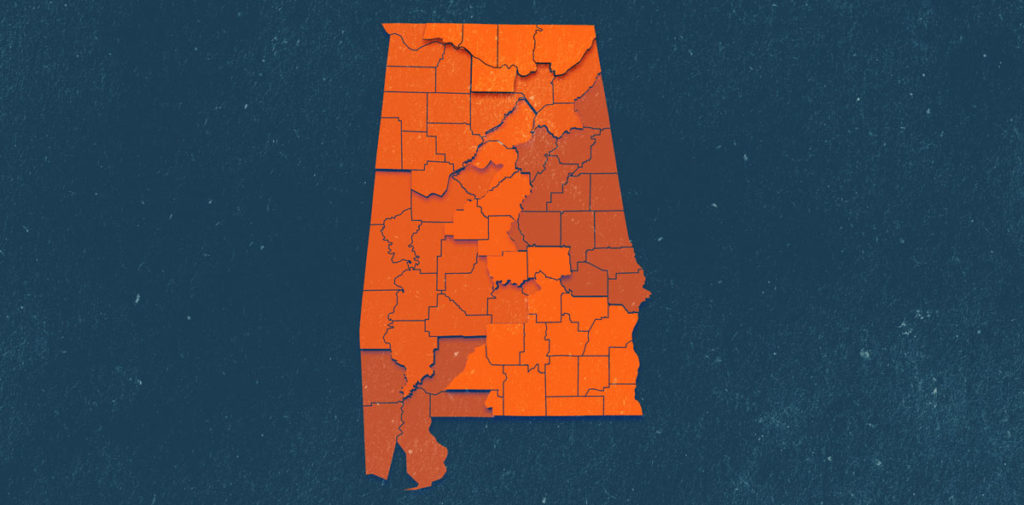

In 2020, the Census may strip a congressional seat from Alabama (seats are allocated based on a state’s total population as determined in the Census). That’s because, in addition to growing at a slower rate than other states, Alabama finds itself dead last in the country in responding to the Census as of mid-September. This should not be tenable to Alabamians. If more people don’t respond to the census, states like California will get both our congressional seats and the federal funding (your own tax dollars) that we otherwise would receive had more of us answered a simple form.

This means that, on top of the normal changing of district lines to account for population shifts, Alabama’s congressional delegation will be influencing hard to not end up in the district with two incumbent Members of Congress vying for one seat in the House (although that election will certainly be one of the more interesting ones of Alabama history).

As for the state legislature, the Census will also require those districts to be redrawn to account for an increasingly urban and suburban population (although there will remain 105 House and 35 State Senate districts). This promises to take up all the air in the State House, making large policy shifts in other areas even more difficult. This reality is another reason Governor Ivey should consider a special session this year to address coronavirus-related issues in which legislators won’t be distracted by redistricting.

Regardless, the redistricting process, which will occur during the 2021 regular session, is lengthy and detailed. Multiple public hearings will be held, maps will be drawn and redrawn, and the legislature will have to debate the fully redistricted Alabama in open session. Compared to other states which allow their legislatures to draw their district lines, this process is notably transparent.

As with any situation in which power is at stake, there is, however, the opportunity for corruption. Legislators looking to benefit themselves through the redistricting process, whether by following Mr. Obama’s lead and giving themselves a wealthier constituency or by ensuring their competition is in another district, will be given the chance.

Thankfully, there is a check on this power: the people. The system, in order for it to work correctly, requires residents of Alabama to understand that they have a role and a responsibility in government decisions, including the redistricting process. As transparent as the redistricting process is compared to other states, a window is worthless if it isn’t used.

When the Alabama Legislature holds its hearings across the state regarding newly-drawn district maps, the audience should be full of residents ready to look through the window and give a well-informed opinion. As the process continues, Alabamians ought to be calling their representatives with input. Believe it or not, these small efforts create real impact and reduce opportunities for smoky secret deals.

If, however, we sit back and ignore the entire process and the window into it we’ve been given, we best not be surprised when we later find out what’s gone on in the room where it happens.

To see a new report on the status of the 2020 Census in Alabama, click here or visit alabamapolicy.org.

Parker Snider is Director of Policy Analysis for the Alabama Policy Insitute.