(News analysis by Quin Hillyer)

The rest of Alabama may want to watch to the race for mayor in Mobile, where fiscally responsible reformer Sandy Stimpson is trying to ward off a comeback attempt by liberal former mayor Sam Jones.

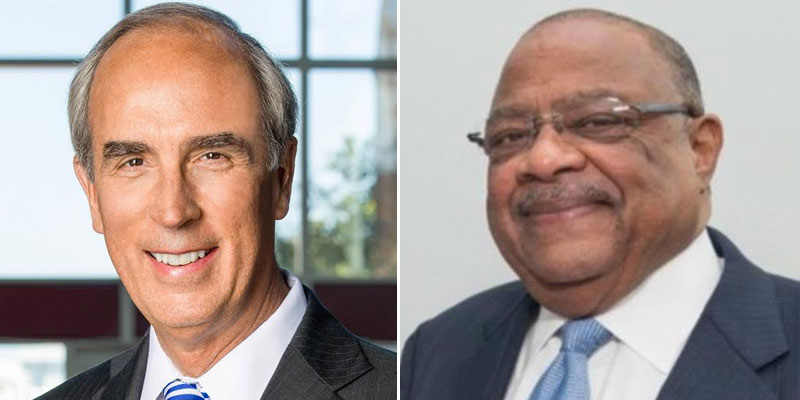

Stimpson, a leading timber executive with a long and varied record of local and state civic leadership, defeated Jones in a mild upset in 2013. Jones is a former Navy man who served for 16 years as a Mobile County commissioner before his two terms as mayor. Election day is August 22.

As County Commissioner, Jones built an image as a moderate-liberal, at least semi-friendly to business interests, who preferred building coalitions rather than making waves. Jones became Mobile’s first-ever black mayor in 2005 by defeating white Republican former city councilman John Peavy, when black voter registration still was less than 45 percent of the electorate. After a mostly uncontroversial first term, Jones was re-elected without opposition in 2009.

Jones’ second term, though, was marked by reports of sloth, mismanagement, lack of transparency, and some economic stagnation, along with the embarrassment of having lost a cruise-ship contract after the city had spent a fortune building a new ship terminal.

Jones also appointed or re-appointed leaders to the local public housing board who, in the words of publisher Rob Holbert of the moderate Lagniappe Weekly, “allowed this city’s public housing to disintegrate to such a degree that much of it looked like it belonged in the Third World.” The Mobile Housing Board now is under investigation by the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development – but that didn’t stop Jones from taking a job (after he left office) from longtime board chairman Clarence Ball, who oversaw the whole mess.

By the time Stimpson ran against Jones in 2013, Mobile’s black voter registration had exceeded 50 percent. But Stimpson, who has a winsome manner and exudes goodwill, carefully built a biracial coalition while pushing a unifying motto of “One Mobile.” Stimpson won comfortably, with 53.5 percent of the vote.

Since then, Mobile’s government has improved by almost every metric. Using figures provided by Stimpson’s administration (but not known to be controverted by anybody), the city’s debt (including bonded indebtedness, which most cities usually carry) has been cut by $72 million, after rising by $123 million during Jones’ first six years. (Jones added no bonded debt during his final two years.) Under Jones, Mobile had no reserve/rainy day fund (and indeed posted a $4.3 million operating deficit once bills were paid for 2013), but Stimpson now maintains a reserve fund of more than $20 million (with no new taxes or other new revenue sources).

When Jones left office, there was a backlog of “infrastructure” needs, with no money specifically dedicated to the purpose. Stimpson (and the City Council) now have dedicated $21 million annually for repavings, new sidewalks, and construction.

And both Moody’s and Standard & Poors have given Mobile better credit ratings (Moody’s had previously described a “negative outlook”), due largely to what S&P called “the city’s improved management practices” which (as Moody’s put it) “has improved the budgeting strategy.”

According to Paul Wesch, Stimpson’s budget director and acting chief of staff, the administration (again, sometimes needing the support of the City Council) achieved its tens of millions of dollars of savings, without cutting any services, through a number of means. The mayor used attrition (from retirements and ordinary turnover) to cut city employment from 2,501 to 2,277 by reassigning duties and increasing productivity. He also urged department heads to provide better oversight, so overtime hours (and pay) have been cut substantially.

“The way some of that is being achieved is through technology,” Wesch explained. “One of [Stimpson’s] first initiatives was to replace aging, unconnected, multiple software systems with a new citywide software system.”

The administration also aggressively managed the city’s “rolling stock” – police, fire, and rescue vehicles. Wesch explained that under Jones, the city’s 500 police cars were being replaced at a pace that each cruiser would need to last an average of 18 years before being replaced. Police would be using old, beat-up cars, hideously expensive to maintain.

Stimpson’s team is now replacing 100 each year (again, using money from its administration-wide management savings), so each car will be expected to last about five years – much more reasonable considering the wear-and-tear endemic to policing. While the front-end outlay is high, almost the whole the cost is recouped on the back end: Instead of replacing transmissions or major parts to keep vehicles moving, mere oil changes suffice. Result: Garage costs are down, Wesch said, from about $10 million annually to about $6 million.

The new cars almost pay for themselves, and the cops are a lot safer.

Among other accomplishments during Stimpson’s first term:

- • Attraction of a new cruise ship contract; a comprehensive new city land-use plan with copious public input; the start of a new 12-mile parkway/bikeway

- • Attraction of major distribution centers for Wal-Mart and Amazon; new management for the troubled housing board

- • An aggressive plan (and implementation thereof) to reduce blight, with blighted properties improved at a rate of about 90 per year instead of the prior 30-40)

- • Insistence on performance-based contracting

- • Creation of a new business “tech corridor”

- • Three pay raises for firefighters and police

- • A string of awards from various national good-government/good-management outfits

Against all this, Jones argues that the city still hasn’t “united” under Stimpson, and he has blasted the current mayor for spending some $80,000 for police overtime and other costs related to Donald Trump’s two famous visits to Mobile (one as a candidate, one as president-elect). The section of Jones’ website called “Achievements” is heavier on promises than on past accomplishments, but four of the six specific achievements listed harkens back to his time on the county commission rather than as mayor.

Lagniappe Weekly’s coverage of Jones’ candidacy announcement (I was unable to attend) indicated, with plenteous examples, that the event was heavy on appeals to racial solidarity, as it “hammered home to those in attendance the importance of strong voter turnout among the city’s black majority.” The lady who introduced Jones, Jessica Norwood, tying Stimpson to Donald Trump, warned of “a darkness moving around the country… [which] got invited into Mobile, and I’m here to say all we have to do is get it out.”

On the other hand, in tune with Jones’ earlier reputation on the county commission for stressing moderate themes rather than stressing racial differences, his web site has a section saying “government alone can’t teach our kids to learn – they know that parents have to teach, that children can’t achieve unless we raise their expectations and turn off the television sets and eradicate the slander that says a black youth with a book is acting white.”

In May, a WALA-TV poll found Stimpson with an overall approval rating of 73 percent, including 60 percent favorability among black voters.

“It would be terribly difficult for Stimpson to mess this up,” said local political consultant and analyst Jon Gray, who oversaw the TV station’s poll. “Can Sam win? Certainly, it is possible. But Sandy’s leadership, plus his having a million dollars in the bank, and the recent polling results, all indicate that would be very unlikely.”

Most local handicappers seem to agree: If he can continue his hard-won image as an inclusive, race-neutral unifier, despite any appeals to the contrary from the Jones camp, Stimpson will enter the home stretch as a somewhat, but not prohibitive, favorite.

Quin Hillyer, a Contributing Editor for National Review Online, lives in Mobile.