Prior to the American Revolution and more than a decade before the French Revolution, there was the Swedish Revolution, which marks its 250th anniversary this month.

While often out of the orbit of discussions of western civilization, Sweden was and continues to be a repository of enlightened democratic values. With a remarkable history of military conquest and constitutional government, the semiquincentennial of the Swedish Revolution is worth noting.

Sweden is known for having divided government. It began in the Middle Ages with a Riksdag, a parliament of nobility, which elected a king and created a balance of authority between the legislative and royal branches. Realizing that electing a king wasn’t a road to stable government, the Riksdag eventually established a hereditary monarchy that remains in effect today.

As with all silos of power, there exists a tension, and in Sweden, there was test of strength between the authority of the king and the power of parliament. Two-and-a-half centuries ago, the Riksdag had the upper hand, allowing the nobility to effectively govern the country with limited approval of the king.

But the parliament became very dysfunctional, lost its way, and engaged in an internal struggle. To accrue power, one parliamentary faction decided to seek an alliance with Russia.

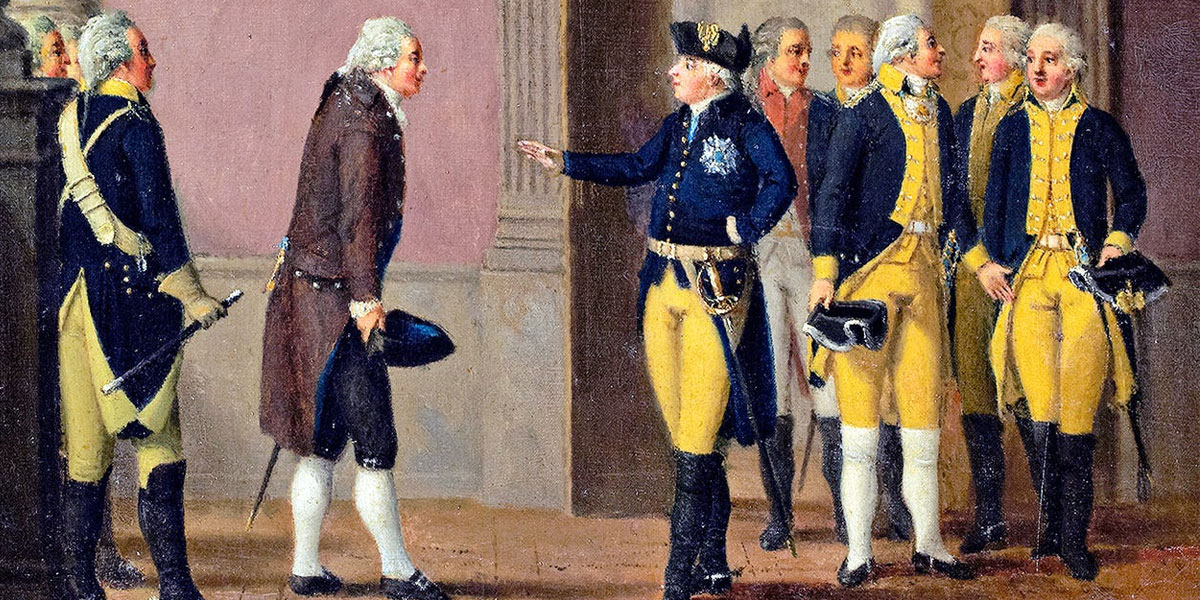

Russia and Sweden have historically been natural enemies, so any link between the two was more than just a political issue for parliament. And, once King Gustav III discovered this attempt, he organized his home guard, whipped his subjects into a patriotic fervor, and marched on the Riksdag.

His success was far from certain. Gustav’s authority had diminished so much that his actual power was limited to his force of personality and rhetorical skills. But, if he knew one thing, it was that Sweden’s interests and Russia’s interests could never be aligned. For Sweden to remain sovereign and independent, he had to act.

So, against type and contrary to perhaps all other revolutions, the ruling king in power became the revolutionary.

When the members of the Riksdag saw Gustav marching toward their chamber, they fled, and with no one left to oppose him, he asserted his rights as king and governed.

This was a bloodless coup, the preferred form of revolution when it is so clear that one side has both the moral and popular authority to force the collapse of the opposition and win by acclamation.

Gustav was the right monarch at the precise time when his country needed him. He was a product of the Enlightenment with very progressive views of government and the ordering of a country.

He took his role seriously and used his power, which was initially only a title and an appeal to his forebears. But the people, led by an emerging middle class, rallied to his side, and once his status was confirmed, he took power and authority by simply inserting himself in the political process and acting like an absolute monarch.

With no opposition of any consequence, he assessed the political landscape and called the parliament back into session.

Using all the trappings of his office, he excoriated the members and accused them of neglecting their duty to their country by placing themselves above the law. His final act to complete the coup was to present the assembly with a new constitution. Once it was unanimously accepted, Gustav dissolved the parliament.

He was now firmly in control of his country, and while he had the momentum and power to become an absolute monarch, he declined.

Since the traditions of Sweden would not countenance despotism, he used his popularity to create a new parliament with less influence by the nobility and more responsive to the people.

He moved to punish those who had compromised the country and went so far as to put corrupt judges on trial. While he could have dispensed justice himself, he understood the importance of the rule of law and forced judicial officers to answer in court for their misdeeds.

His reforms were significant, quite progressive, and liberating to his people. While the Lutheran Church was the established church, he promoted greater religious freedoms by permitting other religions to practice their faith without fear of persecution.

His economic reforms promoted free trade by abolishing export taxes which created economic growth. This contributed to a burgeoning middle class, and Sweden’s wealth increased significantly.

Realizing Sweden’s place in the middle of Scandinavia, he bolstered his army and made his navy a force of reckoning. He was able to deal with Russia and prevent any its nefarious intentions to thwart Sweden’s sovereignty or compromise relations with other nations.

He also liberalized the press, which was not “free” in the manner we think of it today, but it was substantially changed so that censorship and regulations were more limited.

Perhaps most interesting for Americans is that Sweden was the first country to diplomatically recognize the United States. Gustav not only recognized the United States, but he was fascinated by American ideals indicating that if he were not king, he might go fight on their side.

He also suggested that the principles spawning the revolution would make America a rival to Europe and usher in “an American Century.” His summary of the impact of the American Revolution was most prescient.

But inasmuch as he supported the Americans, he was opposed to the French Revolution and worked to restore the monarchy. Like other progressives of the time, he understood that the French Revolution was not a move toward greater liberality, but was, instead, a revolt against maturity.

Many of Gustav’s reforms came at the expense of the nobles and diminished their power. His authority and cultural influence so infuriated them that they assassinated him.

The current king of Sweden, Carl XVI Gustaf, calls his ancestor, Gustav III, his favorite.

At a time when Sweden is once again forced to consider its place in the world and counter the continuing influence of Russia, the reign of Gustav is a good road map for championing freedom by isolating enemies.

Welcome to NATO!

Will Sellers is a graduate of Hillsdale College and an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of Alabama. He is best reached at [email protected]