Four hundred years ago, Charles I was crowned King of England. He became king automatically upon the death of his father, James I, but his coronation was delayed for almost a year.

Officially, the delay was attributed to an outbreak of plague which made public gatherings deadly when, in truth, the excuse masked another reality.

Charles was broke.

His father had spent lavishly and left the crown deeply in debt. Along with the throne, Charles inherited the existing financial obligations and a strained relationship with Parliament. If Charles believed Parliament would fund an extravagant coronation, he would be sorely mistaken.

As the delay lengthened, public anxiety grew. The coronation was not necessary to crown Charles as king, simple heredity did that, but it was a vital public display of royal power and legitimacy. Held in Westminster Abbey, the coronation was a religious ceremony meant to demonstrate that God had anointed Charles as the nation’s ruler, uniting him with his people in a sacred bond of divine favor for a righteous and prosperous reign.

Charles embraced the doctrine of the divine right of kings, which he believed conferred spiritual authority upon him, especially in his dealings with Parliament, and sanctified his royal decrees. Parliament did not share this view. While many respected the king as an essential part of government and an integral element of English society, few believed he was infallible, above the law, or entitled to unquestioned obedience.

When the coronation finally took place, it lacked the grandeur traditionally associated with a new reign. There were no elaborate clothes, feasts, parades, or public processions; nothing for the king’s subjects to enjoy or celebrate. Instead of uniting the kingdom around a hopeful beginning, Charles’s coronation was restrained and joyless.

Rather than fostering kinship, Charles alienated his subjects. Religion remained a matter of paramount importance as many English people remembered the turmoil that occurred when monarchs embraced unpopular religious policies and enforced conformity through persecution. It had been less than 70 years since state-sponsored religion had sanctioned the persecution and execution of religious dissidents.

Instead of easing these concerns, Charles exacerbated them by marrying a French Catholic princess for political reasons. Because the coronation was a Protestant ceremony, she did not participate but observed from behind a screen. Rather than reassuring his subjects of religious moderation and tolerance, the coronation intensified fears that his wife’s influence would shape the king’s faith and policies. No one welcomed the thought of persecutions and instability.

When Charles I ascended the throne, English colonization in America was still tentative and fragile. Jamestown had survived only through great hardship, while Plymouth Colony remained small and precarious. Colonization during Charles’s reign relied on joint-stock companies, proprietary grants, and royal charters. Although Charles did not prioritize colonial expansion, his policies indirectly shaped colonial growth through the granting and confirmation of charters.

Under Charles, colonies such as Massachusetts Bay and Maryland expanded.

The Massachusetts Bay Company received its royal charter from Charles, allowing Puritan leaders to establish a colony with an unusual degree of self-governance. Charles approved the charter largely for financial and political reasons, viewing colonization as a means of expanding English influence without heavy royal expenditure. His treasury also pocketed the franchise fee associated with the charter.

In contrast, Charles’s support for Maryland, granted to Lord Baltimore, was less about remuneration and reflected his desire to reward loyal supporters and provide stability for English Catholics. Maryland was intended as a proprietary colony where Catholics could worship freely, though it ultimately attracted a diverse population. Through these grants, Charles unintentionally shaped the religious and political diversity of the American colonies.

But Charles I’s religious policies also encouraged emigration. His support for the Church of England and a High-Church Anglican style of worship alienated Puritans, who sought further reform and feared a return to Catholic practices.

During the period when Charles ruled without Parliament, religious conformity was more strictly enforced, and dissenters faced fines, imprisonment, or social marginalization. For many Puritans, particularly those with the financial means to relocate, America offered an escape from religious intolerance. Tens of thousands migrated to New England, where they established communities centered on religious autonomy.

The colonies became havens for groups seeking greater religious freedom, reinforcing patterns of self-governance and local political organization that would later define colonial political culture.

Charles’s frequent use of prerogative power, including taxation without parliamentary consent, further alarmed his subjects. These tensions extended to the colonies, where settlers closely followed political developments in England with alarm.

Charles’s inability to tightly supervise colonial affairs allowed colonies to develop representative assemblies, local courts, and systems of taxation modeled on English institutions. This autonomy fostered a political culture that valued local control and resistance to distant authority. The failure to impose consistent royal oversight further entrenched colonial self-rule as colonists experienced liberty to govern themselves in local, representative governments.

The outbreak of the English Civil War significantly altered migration patterns to America. Emigration increased as royalists, parliamentarians, and religious minorities sought safety overseas. New England attracted supporters of Parliament, while colonies such as Virginia and Maryland received greater numbers of royalist sympathizers.

Parliament’s execution of Charles I marked an unprecedented rejection of divinely ordained monarchy. In America, the absence of a monarch and the instability of Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth reduced centralized oversight of the colonies. Under this benign neglect, colonial governments consolidated power and refined local institutions, laying the groundwork for future resistance to imperial control.

The experience of self-governance during a period of imperial weakness reinforced colonial expectations of autonomy. Colonists grew accustomed to managing their own affairs and interpreting English liberties in local contexts. These habits would later shape resistance to British reforms and ultimately contribute to the American Revolution.

Charles I’s coronation 400 years ago increased colonial development both in terms of the people who left England and in the English institutions and practical experiences they brought with them. Through charter grants, religious policies, and political conflict, he inadvertently influenced migration to the colonies and allowed colonial self-government to prosper.

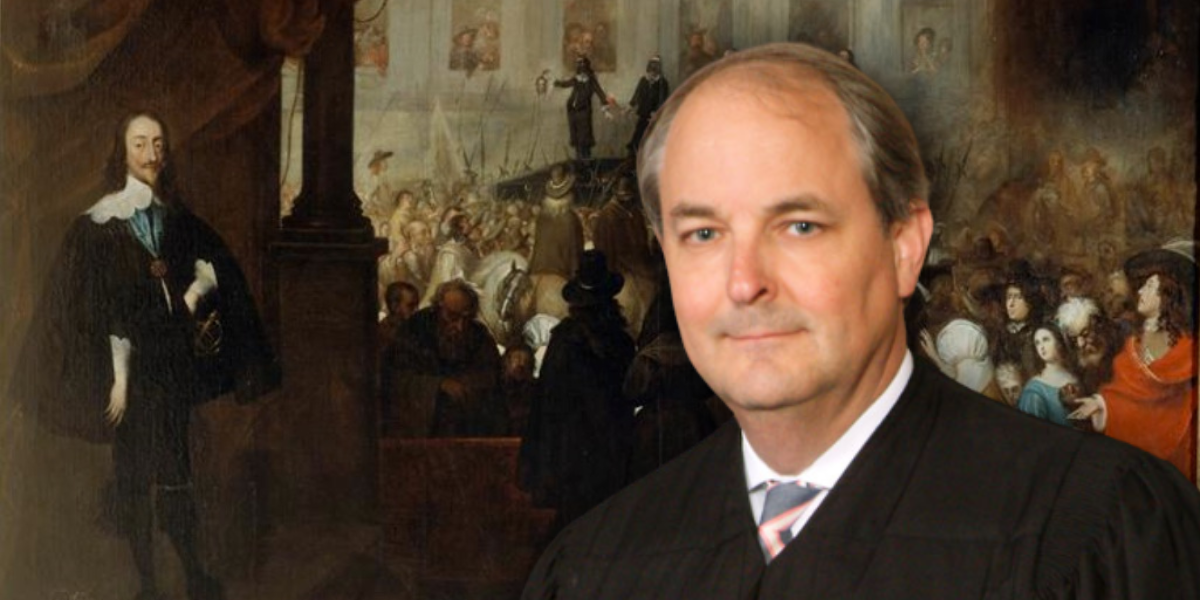

Will Sellers is a graduate of Hillsdale College and an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of Alabama. He is best reached at [email protected].