MONTGOMERY, Ala. — What if many of the over 5 million Americans who have some level of security clearance were not fully vetted before gaining access to the U.S. government’s best kept secrets?

In 2011, that is exactly what Blake Percival realized was going on.

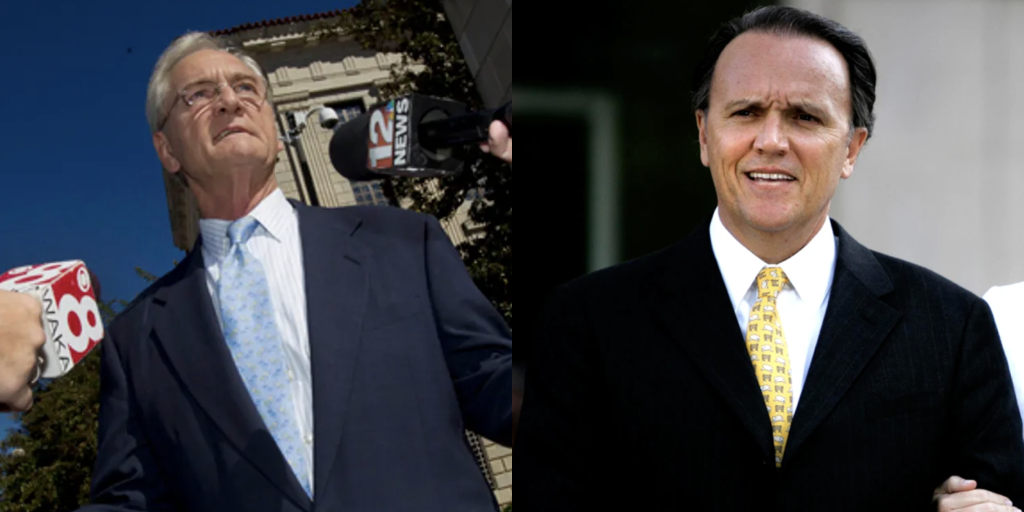

Percival was settling into a new job making the most money he ever had ($110,000/year, plus bonuses and stock options) at a company called USIS. The company was a contractor for the U.S. government tasked with doing in-depth background checks on individuals applying for security clearances. Percival said this made him and his colleagues the “front line of defense” in making sure only the most trustworthy applicants were approved.

But something was wrong, according to a detailed account published by the Washington Post.

While getting to know the people in his new office, Percival asked what they liked least about their jobs. “I hate that we dump,” one of them said.

It was the first time Percival had heard the term, and he asked what it meant. The response shocked him.

“One of USIS’s dirty little secrets is that we’re not reviewing every case we send to OPM,” said Percival’s co-worker. OPM refers to the Office of Personnel Management, which processes most of the country’s security clearance applications.

In short, “dumping” was the term the USIS staff used for cutting corners. Instead of doing the detailed field work required to vet individuals seeking security clearances, USIS was simply giving their stamp of approval to as many applicants as they possibly could. Among those applicants were Edward Snowden, who went on to leak highly classified information on the government’s spying programs, and Aaron Alexis, who is now know as the Washington Navy Yard shooter.

After digging into his co-workers’ allegations, Percival found that USIS was pretending to do its job in order to meet revenue targets. The more applicants they vetted and approved, the more they were paid. OPM at one point appears to have suspected USIS of cutting corners, because one of the agency’s staffers sent a letter to the company in 2011 asking how just four investigators could complete 13,000 reports in a single week.

Percival told his subordinates that from that point forward, they would do the job right.

“As of this moment, we do not dump,” he declared. “If anyone tells you to dump, you send them to me.”

That decision ended up getting Percival fired. After his division missed its revenue targets for several months in a row, he was terminated and told it was because of his “management style.”

The company tried to get him to sign a severance agreement that would have paid him over $40,000, but it would have required him to waive his right to file a False Claims Act lawsuit. He balked.

Percival set up a meeting with powerhouse Alabama law firm Beasley Allen and told them what he had uncovered during his time at USIS. A lawsuit was filed almost immediately detailing his allegations and sending shockwaves through the U.S. national security community.

The United States Department of Justice later joined the suit, alleging that a jaw-dropping 665,500 security clearance cases had been “dumped” by USIS over a four year period. Documents obtained by the DoJ “confirmed that USIS senior management was aware of and directed the dumping practices. This practice was followed in order to meet USIS’s internal goals for completed cases and, therefore, to increase the company’s revenue and profits.”

Unfortunately for Percival, as the lawsuit made its way through the legal system, there was not much that could be done about his career being derailed.

He was trying to provide for his wife and three children by stocking shelves at a local grocery store where the manager was kind enough to allow him to take home expired meat for dinner. There were times when he regretted being a whistleblower. As of early last week, Percival had exactly $54.41 in his bank account, according to The Post.

But today, everything is different.

The lawsuit resulted in a $30 million settlement between USIS and the U.S. government. And over four years since his ordeal began, Percival finally received his share of the settlement, which amounts to over $3 million.

“How does it feel to be a millionaire?” He called and asked his wife.

They plan to throw out the expired meat left in their freezer.

(h/t The Washington Post)