Alabama women today hold political office at local, state and national levels. In 2018, Alabamians elected Gov. Kay Ivey as the state’s second female governor, raising her to the top leadership post.

But it has not always been that way. More than 100 years ago, a woman’s place was in the home. She had no legal rights, and it was considered by many unnatural for her to take part in political affairs.

That began to change with the passage of the 19th Amendment giving American women the right to vote. This year, Alabama and the nation will celebrate the centennial of that pivotal, life-changing moment.

Alabama history professor shares importance of 19th Amendment from Alabama NewsCenter on Vimeo.

Alabama women stand up and fight

The women’s suffrage movement in Alabama began in 1892 in Decatur and later became a statewide crusade. It was launched by women who were battling social issues, such as wiping out child labor and eradicating alcohol consumption and the ills associated with it.

“These women all realized they would never be able to change these social problems until they could vote,” said Valerie Pope Burnes, associate professor of history at the University of West Alabama in Livingston. “They knew that instead of trying to do cleanup once the damage had been done, they had to vote for the people who made the laws and stop the problems before they start.”

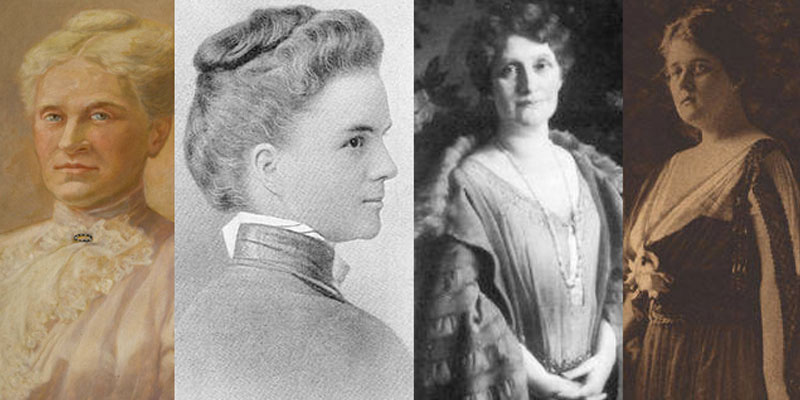

Burnes pinpointed four Alabama women who were most instrumental in bringing about change. Frances Griffin, a teacher from Wetumpka, led the way. She was the first woman to address a legislative body in Alabama when she spoke at the state’s Constitutional Convention in 1901.

During her speech, Griffin effectively shot down the men’s excuses for refusing to give women the right to vote, such as they were not educated and didn’t want to vote. She pointed out that more women attended secondary schools and colleges in 1901 than men, and women “neither steep themselves in tobacco nor besot themselves with liquor, so that whatever brains they have are kept intact.”

Griffin spoke out against men’s actions in the political arena.

“Frances Griffin told the audience that ‘politics is corrupt because women have been kept out of it, and women will clean it up,’” Burnes said.

Burnes said there was one short-lived victory for women during the convention. The delegates voted to give women the right to vote on municipal bond issues. But the men changed their minds the next day and rescinded the decision.

Griffin took her message outside the state, speaking to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). She ran the suffrage movement in Alabama during 1903-1904. Griffin then stepped back from the fight in 1905, temporarily slowing down the movement in Alabama.

The women’s suffrage movement was renewed in 1910 with the founding of the Selma Equal Suffrage Association (SESA). Another activist, Hattie Hooker Wilkins, who later became a state legislator, was one of the movers and shakers in SESA, and helped spread the word by setting up a traveling library with suffrage books and pamphlets.

Pattie Ruffner Jacobs was both a state and national leader in the movement, founding the Birmingham Equal Suffrage Association (BESA) and later serving on the NAWSA board.

Believing that women could accomplish more by working together, the Birmingham and Selma groups joined forces to create the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) on Oct. 9, 1912. The new organization aligned its views with those of NAWSA.

AESA held “voiceless speech demonstrations” in Birmingham department store windows. Members stood in the windows and turned the pages of suffrage pamphlets, making it easier for passersby to read them. AESA opened a tearoom downtown where working women could eat lunch and take a break.

“The suffragists were upper-class white women, but they didn’t want voting to be a class issue,” Burnes said. “The tearoom was a place where girls who worked in the factories and shops could come and read suffrage materials while they took their lunch break.”

Burnes said along with class, race played a role in the movement. “Many Southern white women who advocated the right to vote did so at the expense of African American women,” she said.

Adella Hunt Logan, an African American writer and educator at Tuskegee Institute and another Alabama crusader, was the woman who made the biggest impact in fighting the racial battle, Burnes said. Logan fought for universal suffrage for all women, no matter their race. She joined NAWSA after being inspired by a speech given by women’s rights advocate Susan B. Anthony at the 1895 convention in Atlanta.

AESA members persuaded Joseph Greene, a Dallas County state representative, to bring forward a suffrage bill in the Alabama House in 1915. When the representatives began to debate the issue, he gave a speech against his own bill and withdrew his support. Although the gallery was full of suffragists and legislators wearing yellow roses in support of the issue, the bill to add an amendment to the next ballot granting women the right to vote failed.

The suffragists nicknamed Greene the Dallas County Acrobat because he “flip-flopped” his position. In a twist of fate, Wilkins later defeated him when she was elected in 1922 as the first female Alabama legislator.

In 1919, the issue had moved to the national front when a federal suffrage amendment was sent to the states for ratification. Alabama led the drive in the South to ratify the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. But the state legislators refused to pass it, rejecting any infringement on their authority by the federal government.

“People were really watching Alabama. They figured if Alabama could break open the ‘Solid South’ for suffrage, the rest of the Southern states would follow,” said Burnes. “Alabama women had called and written their legislators, and packed the gallery in the house on the day of the vote. But they were ignored.”

Despite opposition from Alabama legislators, the federal amendment was ratified by two-thirds of the states, giving women nationwide the right to vote. It was officially adopted on Aug. 26, 1920. It was not until 1953 that Alabama ratified the amendment, although it was simply a formality by that time.

Burnes said the suffragists faced many challenges throughout the movement, but the biggest hurdle was the men and their attitudes about women.

“Women had to go through men to get the right to vote,” she said. “The legislators and the citizens who were voting were all males. The women weren’t voters, so the legislators didn’t have to pay attention to them. They didn’t care.”

Of the four women who played instrumental roles in the movement, Burnes believes Griffin had the biggest impact. She died in 1917 and never saw her dream become a reality.

“Frances Griffin is my hero in this whole thing,” said Burnes. “She was smart, witty and broke through the barriers, and she honestly didn’t care what anybody said about her.”

Alabama is celebrating this momentous milestone for women with many centennial events across the state. Vulcan Park and Museum kicked off the celebration in January with a year-long exhibit, “Right or Privilege? Alabama Women and the Vote.” To check out other events on tap this year, visit the Alabama Department of Archives and History Women’s Suffrage Centennial website at alabamawomen100.org.

(Courtesy of Alabama NewsCenter)