American society, and human civilization for that matter, rests on a constantly shifting balance between those who wish to preserve the past and those who seek to build the future, between those who value order and those who desire to unleash freedom, and between those who accept the world as it is and those who wish to shape it into what it could, someday, become.

There’s a little bit of everyone in each of those camps, but when opinions of all major issues are considered, people mostly lean toward one side or the other — the left or right side of the political spectrum. It’s a completely natural and surprisingly necessary balance once you dig into the reasons for each, and the healthy tension between the two sides in America has fostered an unprecedented level of knowledge, strength, and prosperity.

But …

But lately the left and right have stopped talking. Each side believes itself to be morally superior, and consequently, that the other side is morally inferior and not worth learning from, not worth negotiating with, and not even worth listening to.

We’re a house divided, or close enough to it to be worried.

But for those who still see value in our union, and who still want to live together, it’s critically important to understand not just “what” we think, but “how” we think, and most importantly, “why.”

What follows is my best effort to explain the “how” and “why” from my own perspective — a traditional, conservative one that would have been familiar to Ronald Reagan or William F. Buckley, Jr., in hopes that it’ll be of some value to both sides.

Why are there Conservatives and Progressives?

The division we’re seeing now is really nothing new. In fact, many believe the roots of how we understand modern conservatism and modern progressivism, and the arguments between the two, began way back in the Enlightenment.

Enlightenment thinkers were keen on discussing human nature, believing if we could understand human nature, we could then understand how to better govern ourselves.

One popular idea was John Locke’s theory of the blank slate, or if he were alive today, perhaps the blank emoji.

In this state, all men are born knowing equally nothing, thus all men are created equal, and the type of person we become is entirely caused by our own unique experiences. And if man were left alone in this pristine state of nature, and not influenced by the corrupting aspects of the world, we’d all essentially develop into good people — we’d all be the angel emoji. .

We’d only need a light social contract to preserve our natural rights, our natural liberties.

Thomas Hobbs believed very differently. He thought we’re all created with great flaws, and in a state of nature our irrational self-interest would cause us to all become awful people — we’re all the devil emoji. (Read “Lord of the Flies” for a great imagining of this theory.)

So Hobbs believed we needed a heavy contract, surrendering our natural rights to a strong ruler in exchange for him keeping us from killing one another, in exchange for keeping order.

Two polar opposite and competing ideas, one naive and the other dreary. Thinkers kicked them around for a century or so until a revolution occurred that caused them to bring together the best aspects of each and begin the modern conservative movement.

The American Revolution?

No. That was less of a war of true revolution than a war of preservation — preserving what liberty the colonists already had.

The revolution that kindled modern conservative thought was the French Revolution. They tossed out everything, from the ruling class to the church and even the calendar. Every aspect of society was deemed institutionally repressive (sound familiar?).

Liberty. Equality. Fraternity.

And if you didn’t get with the program: Terror.

English and American thinkers looked on in horror at how much bad was being introduced to French society with such little good in return, and began to write about it.

Their basic argument was this: Sure, the enlightenment idea of liberty is important. These natural rights are real and must be protected. (Locke)

But so is order. (Hobbs)

An orderly society is damn hard to create and when order is lost, liberty is lost with it. Only chaos remains, as they saw on the streets of Paris. Rich and poor alike were being robbed and murdered, and in the end, a despot came to power to establish order and quash all freedom, just as Hobbs theorized — Napoleon.

Here’s the key, the American and English thinkers realized — a moderated Hobsian order creates the condition for moderated Lockean liberty. One comes before the other, a healthy society must have each, and they must remain in a delicate and constantly adjusting balance.

Liberty on one side. Order on the other. Too much of one and you get chaos (look at San Francisco) or tyranny (look at Shanghai).

Over the next 200 years the conservative movement began to notice certain ways of thinking, certain perspectives that tended to help society maintain the balance between liberty and order, maintaining a shared sense of boundaries that people could freely operate within.

And while conservatism doesn’t have a list of any doctrines or any sort of catechism or profession of beliefs, the writer and philosopher Russell Kirk did a fine job of combining these various perspectives into 10 general principles.

The first principle is that conservatives recognize that there is an enduring moral order.

We are not blank slates, or blank emogees, and we’ve known this for a very long time.

In chapter two of the Book of Romans, Saint Paul writes this about the Gentiles, who were never taught the laws of God, “They show the demands of the law are written in their hearts.”

All cultures possess a common understanding of morality. We may disagree on the high-definition details up close, but from far away we all see the same fuzzy image of what’s right and what’s wrong.

The ancients believed this was innate, and now modern developmental psychologists agree. Studies are showing that nature provides us with a “first draft” of not only personality, but of morality. As with all first drafts, it is not final, but one that’s later revised by experience, for good or bad. I’ll explain a little more about that in a moment, but conservatives recognize this enduring moral order, however uncomfortable it may make us.

Nations, and certainly individuals, ignore it at their own peril.

The second principle is tradition.

Conservatives understand things like customs, convention, and continuity help bind us to one another, thereby holding the community, and the larger society, together.

Tradition gives us a connection to the past and a stake in the future.

Edmund Bruke put it well when he wrote that, “society is a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are dead, and those who are to be born.”

We have simple traditions, like a wedding ring. We have complicated traditions, like weddings, or marriage itself … which can be very complicated.

We may not understand them all. Some are deeply meaningful in themselves. Some simply enable other meaningful things. But if we start tossing them aside like relics of an uninformed or superstitious past, we may find ourselves floating aimlessly through life, pushed and pulled by currents of reckless and unpredictable winds.

Because even when we demolish traditions, our innate need for order causes us to reestablish them in other forms, which are often inferior and more harmful than those that have been tested by time. (The French Revolution, again, brought so many examples of this. They did away with religion … so the state created a secular religion to take its place, and it was even more corrupt and harmful.)

Traditions keep us moored to something larger, and much studier, than just ourselves.

The next principle is prescription.

This isn’t like a pharmacist’s prescription. We haven’t found the “get smarter pill” … yet.

This is prescription in the legal sense, which is our observation that it is often wise to keep certain things that have been tested by time.

Or, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Generations upon generations have found that certain institutions or specific practices tend to produce the best results, or not.

Collectivism doesn’t work. Never has. Never will. Look at Cuba. Look at Venezuela. Look at the former Soviet Union. Further time and energy spent investing in that experiment should be discouraged, to say the least.

A man and a woman getting married, staying married, and having children generally leads to the best life outcomes — from personal wealth to life expectancy. That lifestyle should be encouraged.

That’s prescription at work.

Here’s a thought experiment to demonstrate the need for the next principle — prudence.

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total.

The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

If you were thinking 10 cents, like most people, then like most people, you’re wrong.

The correct answer to this problem is that the ball costs 5 cents and the bat costs — a dollar more — $1.05 … for a grand total of $1.10.

So why do so many people answer incorrectly? Because we have two track minds: one for thinking quickly and one for thinking things through, slowly. The problem is, we’re often stuck on one track, and it’s the quick one.

That is why conservatives believe in the principle of prudence.

Move slowly, because you don’t know what’s going to happen. Our problems are large and complex. You fix something here and it causes something to break over there.

We should distrust any politician who seems too confident.

Prudence, practically speaking, is putting doubt into practice. Far from pointless naysaying, doubting the best laid plans of mice and men could save money, and more importantly, lives.

Next, conservatives take note of variety.

Conservatism and variety may seem like they don’t go together, but they do. There’s absolutely nothing uniform or stagnant about the free market. There’s plenty of variety there.

But it’s not only the marketplace for goods and services. We seek variety in the marketplace of ideas, of institutions, of traditions.

Contrast that to the opposite ways of thinking: isn’t it interesting how in collectivist systems, everything seems to be uniform – the same ideas, even the same fashion.

Everything’s the same, and even when they express supposed radical ideas or alternative behaviors or even bizarre hairstyles, there’s an ironic sense of conformity to it all.

And that’s the key. Everything ends up being the same because a collectivist seeks equality in life’s outcome, not accepting true variety in life itself. There’s a rational, and even moral reason they feel this way, which I will explain later.

Kirk’s sixth principle of conservatism is imperfectability.

I write with a pencil for a reason. I make mistakes, often, and use the eraser nearly as much as the led.

Conservatism knows this, too.

The left’s central planner, despite all his resources and all his best intentions, will fail to produce the perfect plan, and even if he could, people couldn’t follow the plan perfectly. The results of such efforts on the scale of large governments usually end in disaster.

The Soviet Union promised a worker’s paradise. It delivered the gulags instead. A real hell on earth.

Conservatives say the best we can hope for in the world is a relatively free and orderly society, but some suffering is inevitable.

Seventh, conservatives have learned that freedom and property are closely linked.

The stronger a nation’s property laws – both real property and intellectual property – the freer and more prosperous are its people.

Remember the case of Suzette Kelo, who owned a little pink house near the coast of Connecticut? The town of New London used the constitution’s eminent domain clause, which was meant to allow governments to force private property owners to sell their lands at a fair value to be used for public infrastructure like roads, to force an unwilling Kelo to sell her property so a private company could develop a shopping center.

Our Supreme Court ruled that was permissible.

It’s not, and it never will be in a free country.

By the way, what did the town do with Kelo’s land after it forced her to sell it?

Nothing.

Their big plan for economic development never went anywhere (again, the folly of the central planner). Kelo’s beloved home became a vacant lot, as vacant as the morality the Supreme Court’s opinion was based upon.

Eighth, conservatives believe in the strength of voluntary community interaction, a group with shared interests coming together to discuss and hopefully solve problems.

This best expresses itself in local government.

Progressivism usually seeks centralized authority at the highest levels.

Libertarians usually seek not much authority at all.

But conservatives believe in decentralized, local authority. Those who are closest to the issues are usually positioned to make the best decision.

This isn’t always the case, of course. We have a national military because that’s the best organization for its mission, but we also have local police forces. I have no idea why we have a federal Department of Education, though.

Conservatism’s ninth principle is a belief in prudent restraints.

We have one of the best restraints known to men – the Constitution of the United States of America.

In other nations, their governmental documents lay out what the government can do and shall do. It’s all about “the government can do this” and “the government can do that.”

Not us.

Our governing document is full of statements like “Congress shall not …,” and we famously separate our powers – legislative, judicial, and executive.

In most nations, the legislative and executive functions are combined into a parliament, which would be something like if we only had the House of Representatives. The Speaker of the House would be the Prime Minster, and other members of the majority party would be appointed to run the various executive departments. That allows a government to act swiftly.

Us?

Not so much.

Our framers didn’t want us to act swiftly. They wanted us to act prudently, so they restrained our government every way they could.

Gridlock wouldn’t have been a bad word to their ears, and it shouldn’t be to ours.

Kirk’s 10th principle is how conservatives recognize that permanence and change must be reconciled.

People often say conservatives are resistant to change.

Not so. We’re just resistant to quick or reckless change.

We can add more liberty to the society, but it must be counterbalanced with the appropriate amount of order, even if it’s not a law but a maturing of the society to handle the new freedom.

Slowly, but surely.

Move too fast and you’re likely to produce a counter-reaction that destabilizes what’s good in society, and destroy that which you seek to improve.

Because conservatives recognize the imperfectability of man, we accept that we also don’t know everything yet. There are many things yet to be discovered, and not only in the areas of science and technology, but in our institutions, our government processes, and even in our hearts and minds.

When these changes are discovered, they must be balanced against what is already known and accepted.

The Objective: Ordered Liberty

Well-ordered liberty. That’s the key. That’s the lesson from the French Revolution, and every real revolution before or since. And that’s why conservatives think the way we do – to maintain the balance between order and liberty.

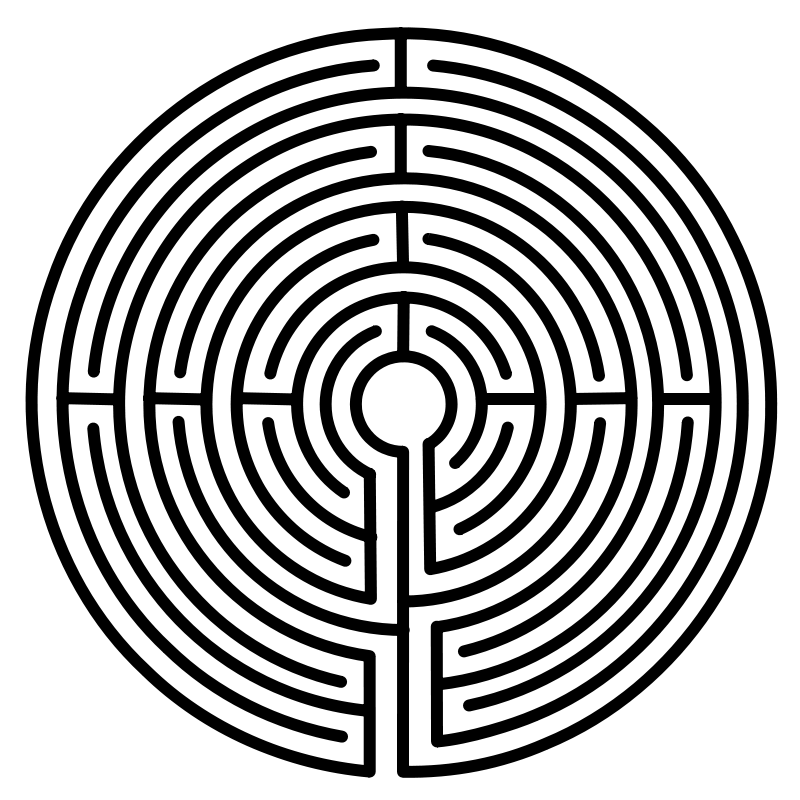

Or, seen through the metaphor of the ancient labyrinth, the ability to move (liberty) within an established boundary (order).

Where are those boundaries? That’s for each society, and generation, to establish and adjust for themselves. And we do it through the application of those 10 principles.

But understanding that doesn’t get to the core of the problem we’re currently facing — the deep distrust each “side” has for the other, how we believe that their ideas are not only wrong, but that their motives are even worse.

That’s simply not a sustainable attitude if we’re going to live with one another. We can disagree, but we really need to get a grip on the idea that those who disagree with us are terrible people who need to be canceled.

Perhaps the pathway out of the problem rests on our understanding that there’s an enduring moral order, because I firmly believe that there are people of good faith, on the left and right, who are making their decisions based on a common moral framework. It’s just that we all pay attention to certain aspects of morality to different degrees, and then make decisions based on what we believe are most important.

Moral Foundations of Conservatism and Progressivism

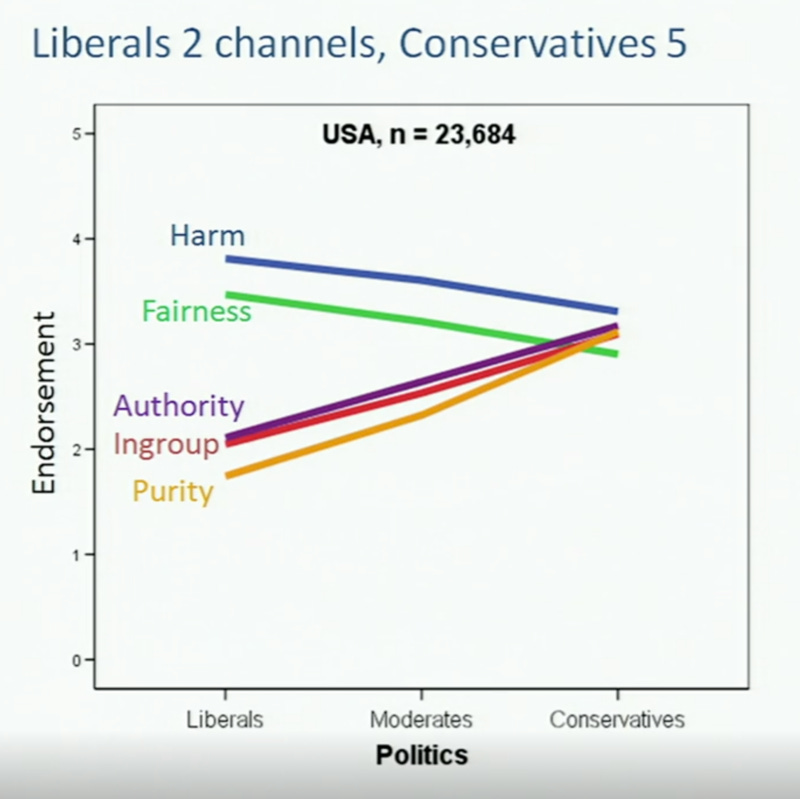

A few years ago, Professor Jonathan Haidt ran a study covering thousands of subjects across several disciplines and cultures looking for morals that we share in common, primed from birth, and found that we indeed have them, and he classified them into five foundations of morality.

- The first is “Harm/Care.” This is what causes us to care for others, to have compassion, to feel strongly about those who cause harm.

- The second is “Fairness/Reciprocity.” This is justice, or basically the Golden Rule.

- “In-Group Loyalty” is the third. This is what causes us to bond first with family, to create communities, nations. Think of it as our tribal instinct, even though that phrase can be understood as something undesirable.

- The fourth is “Authority/Respect.” This is that bit of order I was speaking about earlier.

- The last is “Purity/Sanctity.” This isn’t just about sex. It’s about seeking virtue and suppressing vice, trying to make the best of yourself, and keeping something — maybe your mind, your heart, your body, our environment — pure. For social conservatives, this may be remaining chaste before marriage. For environmental liberals, this may mean abolishing coal-fired energy plants.

Haidt’s research found that liberals score very high in two: Harm/Care and Fairness/Reciprocity, but somewhat low in the other three: Authority/Respect, In-Group Loyalty, and Purity/Sanctity.

Then he found that conservatives tend to care about all of these things equally. No one factor was high or low. They were all grouped somewhere in the middle.

What interests me is the noticeable gap between how much liberals seem to care about Harm/Care and Fairness/Reciprocity, and then how little about Authority/Respect, In-Group Loyalty, and Purity/Sanctity.

That gap could explain why order will naturally decay without effort.

But it certainly explains the role conservatives play in society – they take up the slack in that gap, making sure we have order, making sure our communities are held together, and making sure we seek virtue.

Meanwhile, we have the liberals to focus heavily on Harm/Care and Fairness/Reciprocity.

However you look at the graph, it’s clear to me that we need both sides.

We need Americans focused on treating people better.

We need Americans focused on making sure people are treated fairly.

We need Americans focused on taking care of their families.

We need Americans focused on ensuring we have an orderly society to live in.

And we need Americans focused on keeping us healthy — mentally, emotionally, physically, and spiritually.

Folks like Professor Haidt would say mankind evolved that way to ensure that all of the tribe’s needs were met. I’d largely agree, but only add that I believe it’s all part of God’s plan. He knew, before the world was created, that a guy named Carl would have a strong instinct to protect and would eventually become a police officer in New York City, and that a girl named Joanna would feel the need to instruct little ones and would become a teacher in Nashville.

And he knew that you would care about the things you care about, and that you’d be doing what you are doing.

Because we’re a team.

We need order.

We need liberty.

We need each other.

And if we can treat each with dignity and courtesy, keep talking, and keep our minds open, we might … just might … keep the balance.

(J. Pepper Bryars is Alabama’s only reader supported conservative journalist. You can support his writing by subscribing here.)