The Biden administration is proposing tougher tax enforcement to help pay for the $3.5 trillion budget reconciliation package. Collecting legally owed taxes is a laudable goal, but politicians have historically discounted the compliance costs of taxes. History may be repeating itself.

The most controversial enforcement proposal involves banks and other financial institutions reporting all accounts with an annual cash flow over $600. Groups like the American Bankers Association and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce have heavily criticized the proposal. Since we know that business groups sometimes protest too much, how should we evaluate this proposal?

The administration’s interest in enforcement stems from the tax gap, or taxes that should be but are not paid. A tax gap is inevitable since people respond to incentives, including taxes. People respond to taxes with avoidance, or using loopholes to legally reduce one’s liability, and evasion, or not paying taxes legally owed. The tax gap is based on evasion.

The principle of equality before the law implies that everyone should pay as legally obligated. Many Americans view tax evasion as immoral and support efforts to make cheaters pay.

We do not know the exact size of the tax gap because we lack statistics on deliberately hidden income. Economists Natasha Sarin and Lawrence Summers estimated it at $630 billion for 2020, or about 15% of the taxes that should have been paid. Improved enforcement will never deliver the entire $630 billion to Uncle Sam. If we lowered our tax gap to the smallest observed across developed nations, we might raise an extra $300 billion annually. This will not eliminate the current $3 trillion Federal deficit.

The individual income tax accounts for over 90% of the tax gap and has a larger gap relative to taxes owed than corporate, payroll, or estate taxes. Yet because most Americans’ employers report their earnings to the IRS, they have little ability to evade taxes. “Pass through” business income taxed under the individual income tax is the greatest source of evasion.

The American Bankers Association questions “whether the new reporting requirements would improve the IRS’ ability to identify higher income tax evaders.” I concur. And because most Americans have little ability to evade taxes, data on most bank accounts must be of minimal enforcement value.

Targeting tax evaders is one of several ways politicians portray new spending as costless. Politicians on the left further propose taxing the rich and corporations while conservatives favor eliminating “waste, fraud, and abuse”. Public choice economics predicts that politicians should employ such gambits to obtain as much support as possible while avoiding opposition. Politicians typically win support by giving people things while imposing taxes or other costs produces opposition.

The costs of tax compliance, meaning the costs businesses and taxpayers incur to prepare their taxes and justify their returns in the event of an audit, should factor into politicians’ calculation of net support. Yet portraying new compliance measures as only impacting tax cheats discounts these costs. We feel little sympathy for the cheats and never realize how much our tax preparation costs rise.

Banks have been deputized by Uncle Sam in tax and regulatory compliance. Estimates suggest that compliance accounts for 10% of banks’ operating expenses, even more for small, community banks. Perhaps one out of every ten employees are doing paperwork for government agencies instead of helping customers or reviewing loan applications.

Banks’ compliance burdens have real consequences. Policy makers have recently agonized about “unbanked” Americans who use payday and title lenders (and pay high fees) instead of banks. Yet compliance costs must ultimately be paid by customers and make small accounts increasingly unprofitable. The new reporting requirements should make this worse.

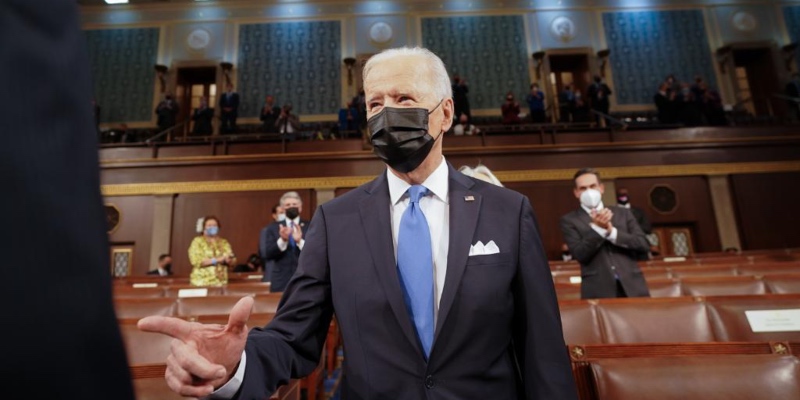

Taxes are one of life’s two inevitabilities, so we scorn those cheating the tax man. But eliminating the tax gap is one of several ways politicians make new spending appear to cost almost nothing. If Americans truly support President Biden’s spending agenda, we should agree to pay higher taxes, not further burden banks.

Daniel Sutter is the Charles G. Koch Professor of Economics with the Manuel H. Johnson Center for Political Economy at Troy University and host of Econversations on TrojanVision. The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Troy University.