The author of this op-ed, Joseph A. Califano Jr., was President Lyndon Johnson’s top assistant for domestic affairs from 1965 to 1969.

What’s wrong with Hollywood?

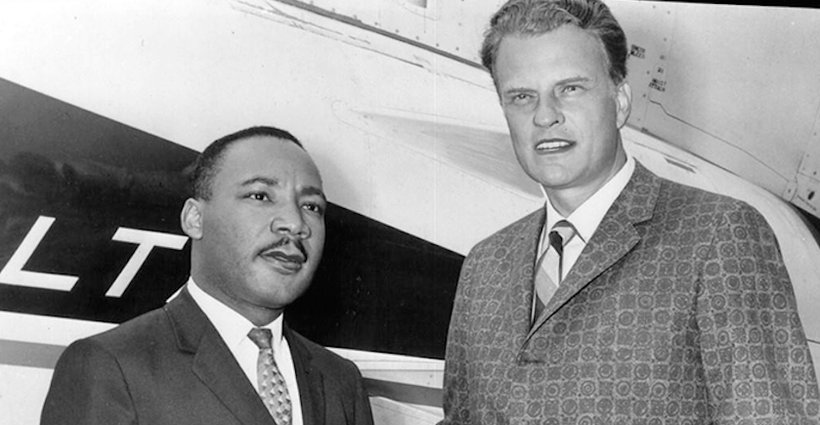

The makers of the new movie “Selma” apparently just couldn’t resist taking dramatic, trumped-up license with a true story that didn’t need any embellishment to work as a big-screen historical drama. As a result, the film falsely portrays President Lyndon B. Johnson as being at odds with Martin Luther King Jr. and even using the FBI to discredit him, as only reluctantly behind the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and as opposed to the Selma march itself.

In fact, Selma was LBJ’s idea, he considered the Voting Rights Act his greatest legislative achievement, he viewed King as an essential partner in getting it enacted — and he didn’t use the FBI to disparage him.

On Jan. 15, 1965, LBJ talked to King by telephone about his intention to send a voting rights act to Congress: “There is not going to be anything as effective, though, Doctor, as all [blacks] voting.”

Johnson then articulated a strategy for drawing attention to the injustice of using literacy tests and other barriers to stop black Southerners from voting. “We take the position,” he said, “that every person born in this country, when he reaches a certain age, that he have a right to vote . . .whether it’s a Negro, whether it’s a Mexican, or who it is. . . . I think you can contribute a great deal by getting your leaders and you, yourself, taking very simple examples of discrimination; where a [black] man’s got . . . to quote the first 10 Amendments, . . . and some people don’t have to do that, but when a Negro comes in he’s got to do it, and if we can, just repeat and repeat and repeat.

“And if you can find the worst condition that you run into in Alabama, Mississippi or Louisiana or South Carolina . . . and if you just take that one illustration and get it on radio, get it on television, get it in the pulpits, get it in the meetings, get it everyplace you can. Pretty soon the fellow that didn’t do anything but drive a tractor will say, ‘Well, that’s not right, that’s not fair,’ and then that will help us on what we’re going to shove through [Congress] in the end.”

King agreed, and LBJ added, sealing the deal, “And if we do that we will break through. It will be the greatest breakthrough of anything, not even excepting this ’64 [Civil Rights] Act, I think the greatest achievement of my administration.”

Selma was the worst place King could find. Johnson met with King on Feb. 9 and heard about King’s choice, a place where just 335 of about 10,000 registered voters were black — despite a population that was 60 percent African American. Johnson thought the public pressure generated by a march from Selma to Montgomery, the capital of Alabama, would be helpful, and he hoped there would be no violence. But there was. On March 7, march leader John Lewis was clubbed to the ground; two days later, when another march attempt was staged, a white minister from Boston was killed. Summoned to the White House, Alabama Gov. George Wallace told LBJ that he couldn’t protect the marchers. That gave the president the opportunity to federalize the Alabama National Guard to protect them.

On March 15, Johnson addressed a joint session of Congress to propose his Voting Rights Act. When the president intoned the anthem of the civil rights movement, “And we shall overcome,” John Lewis, watching the address on television with King, said that King cried.

When the march resumed a third time, on March 17, Johnson made sure the demonstrators would be protected. I was then Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s special assistant. My job was to report to the White House every couple of hours on the progress and protection of the marchers until they reached Montgomery.

For the truth about Johnson, the Voting Rights Act and Selma, listen to the tape of the LBJ-MLK telephone conversation and read my numerous reports to the White House, which have been on the LBJ Presidential Library Web site for years.

All this material was publicly available to the producers, the writer of the screenplay and the director of this film. Why didn’t they use it? Did they feel no obligation to check the facts? Did they consider themselves free to fill the screen with falsehoods, immune from any responsibility to the dead, just because they thought it made for a better story?

Contrary to the portrait painted by “Selma,” Lyndon Johnson and Martin Luther King Jr. were partners in this effort. Johnson was enthusiastic about voting rights and the president urged King to find a place like Selma and lead a major demonstration. That’s three strikes for “Selma.” The movie should be ruled out this Christmas and during the ensuing awards season.

Joseph Anthony Califano, Jr. is a former United States Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare and the founder and former chairman of The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. You can reach him at [email protected].