Researchers from the University of Alabama are shedding light on the issue of raw sewage draining into waterways of the state’s Black Belt region, a problem garnering international attention.

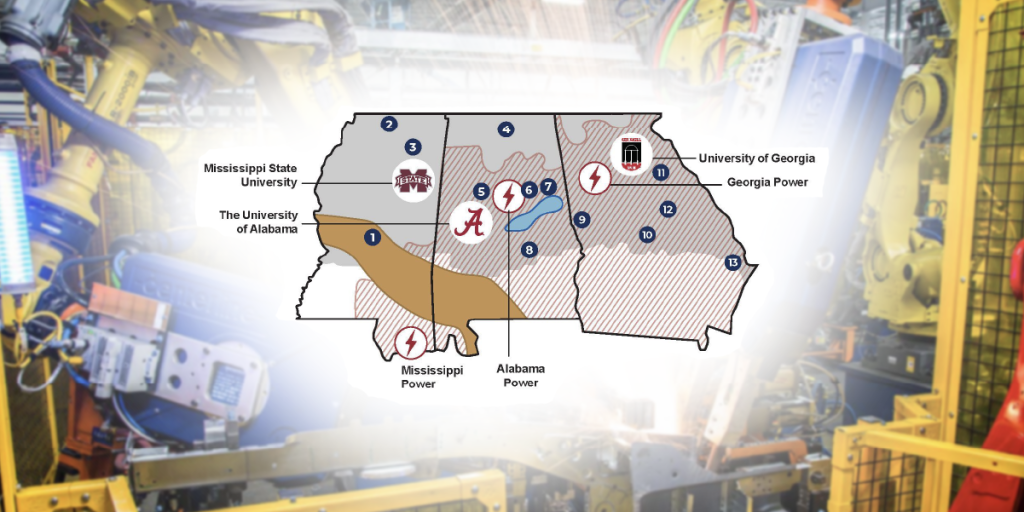

With a grant from the federal Environmental Protection Agency, UA researchers from environmental engineering and geology will build a model to quantify the extent of untreated raw sewage discharges from homes throughout five counties in the Black Belt, an economically depressed region in the state named for its dark, rich soil.

“Basically, the big issue with rural wastewater that we see in Alabama is the confluence of impermeable soil and rural poverty,” said Dr. Mark Elliott, UA associate professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering. “The fact is, though, the scope of that problem is not well understood.”

The situation has brought the attention of the United Nations, which sent an official to examine straight pipe drainage in 2017. There has also been national and international reporting on the conditions as studies have shown diseases and parasites common in tropical areas, and once thought contained in the United States, are appearing in the Black Belt.

Much of the country can dispose of household wastewater safely, either into a sewer system that leads to a treatment plant or into a septic system that uses engineering and natural geology to filter out contaminants before reaching the groundwater.

The Black Belt, an area of 17 counties across southwest Alabama, is often different. Underneath the topsoil is clay and chalk, which holds water. This can cause a backup of a septic system and risk sending untreated wastewater into the streams, lakes, rivers and groundwater nearby.

Added to the soil challenge, the Black Belt is a poverty-stricken area of the country, especially outside its small towns. Many find it difficult to afford advanced septic systems needed for the soil, instead using a straight pipe running from the home to some other part of the property to drain untreated wastewater.

A 2017 survey by Elliott’s group in Wilcox County conservatively estimated that 60 percent of homes drain wastewater without treatment. Elliott said it is possible more than 500,000 gallons of raw sewage enter the rivers and streams in Wilcox County each day.

Site surveys are expensive and time-consuming, so the full extent of straight pipe drainage in the region is largely unknown.

“Not knowing the scope of the problem prevents any sort of estimate of how much it costs to fix the problem or the benefits of fixing the problem,” Elliott said.

Aaron Blackwell, a graduate student in Elliott’s lab, leads the work of making maps to predict the risk of homes using straight pipe drainage. The maps combine geological information of the soil, property values from the county government and population density to show areas where there is greater risk of homes discharging untreated waste through straight pipes.

“Based on a just a few publicly available data sets, we can come up with decent estimates of where these straight pipes are located and how much wastewater is being discharged untreated to the environment,” Elliott said. “This is an important step.”

The maps can show areas where intervention could be effective, such as clusters of homes outside a town that could share a simple treatment system, he said.

The $15,000 grant to UA comes through EPA’s People, Prosperity and the Planet, or P3, program. Research teams receive funding to develop sustainable technologies to help solve environmental and public health challenges. The P3 competition challenges students to research, develop and design innovative projects that address a myriad of environmental protection and public health issues.

UA’s team is in the first phase of the program, and it will attend the TechConnect World Innovation Conference and Expo in Boston in June to showcase its research. The team can then apply for a second-phase grant for funding up to $100,000 to further the project design.

Other members of the team include Dr. Joseph Weber, UA professor of geological sciences; Dr. Sagy Cohen, UA associate professor of geological sciences, and Rebecca Greenberg, a UA graduate student studying geology.

This story originally appeared on the University of Alabama’s website.

(Courtesy of Alabama NewsCenter)