NASA is expected in the coming weeks to select up to two prime contractors to continue competing to build the Human Landing System (HLS) that will eventually land the next man and the first woman on the moon through the Artemis program.

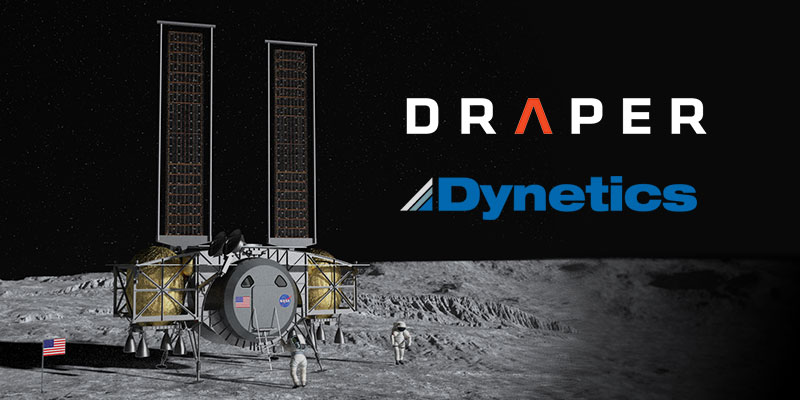

The agency last year selected three prime contractors to design a HLS: Blue Origin, Dynetics and SpaceX.

Dynetics, now a wholly-owned subsidiary of Leidos, is headquartered in Huntsville, and Blue Origin’s work on the program is also being centered in the Rocket City. Of course, Marshall Space Flight Center manages the HLS program for NASA, so the program is about as Huntsville-centric as it gets.

One of the key points Blue Origin has made publicly is the legacy of its team, which the company calls the “National Team” and includes the likes of Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Draper — three storied American defense and aerospace contractors that helped guide the famed Apollo program.

However, an underreported aspect of the competition is that Draper is also a major part of Dynetics’ HLS team.

One of the major stated benefits of Dynetics’ HLS proposal is the sustainability of the system. The Dynetics HLS has been intentionally designed to contribute to the sustainability of the Artemis program in three main ways: reusability, extensibility and supporting the development of a lunar economy. The company believes these three building blocks are vital to the goal of a long-term, sustainable presence on the moon — as well as future human exploration to deeper space, including Mars.

However, Dynetics’ enhanced public focus on sustainability is not to say that its HLS team does not bring significant flight heritage to the table; Dynetics itself has quickly become a “‘go-to’ propulsion provider for partners in both government and industry,” and Draper’s inclusion on the team especially underscores the diverse experience and expertise of the entire Dynetics team — which is also buoyed by the likes of Sierra Nevada Corporation and Maxar.

Yellowhammer News recently spoke with Kelly Villarreal, Space Systems senior program manager and HLS lead for the Dynetics team at Draper; Pete Paceley, principal director of Civil and Commercial Space Systems at Draper and head of Draper’s Huntsville office; and Kristina Hendrix, director of communications at Dynetics.

The discussion included talks about how Draper’s expertise that first landed humans on the moon through the Apollo program is set to be used in an evolved form for Artemis.

“It’s a thrill to be a part of the Dynetics Human Lander team,” said Paceley, an alumnus of Auburn University. “Going back to the moon is a big deal for Draper.”

He explained that Draper, originally part of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was named for the late Charles Stark “Doc” Draper who is known as the father of inertial navigation. He was the founder and director of MIT’s Instrumentation Laboratory, later renamed the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory. That lab made the Apollo lunar landings possible through the Apollo Guidance Computer it designed for NASA as the agency’s first prime contractor for the program.

Draper — the company — was spun off a non-profit in the 1970s into the private sector.

“We like to say we’ve already landed on the moon six times — we have a rich heritage there,” advised Paceley in explaining that Draper provided the flight control computer, all of the software, and the guidance, navigation and control systems for Apollo. “And we’ve maintained that legacy… Draper brings a lot to the party.”

The company opened an office in Huntsville’s Cummings Research Park in 2006, essentially right down the street from Dynetics’ base of operations.

“We’ve had a great relationship with Dynetics over the years on various programs,” Paceley noted, adding the companies have “very complementary capabilities.”

Just like it did for Apollo, Draper is bringing world-class navigation, guidance and flight control software and hardware to the Dynetics HLS team.

Villarreal reiterated Draper’s enthusiasm for being on the Dynetics HLS team and functioning as a “major contributor to the overall effort to return to the lunar surface.”

Draper’s Huntsville office, which employs about 20 people, largely works on NASA programs; another contribution Draper is making in the Rocket City is also on the Artemis program through the Marshall-managed Space Launch System (SLS). The company additionally supports the Missile Defense Agency at Redstone Arsenal and other Pentagon-driven national security work in the area.

While Draper has been there before, a major difference between Artemis and Apollo is that NASA wants to land on the lunar South Pole this time around rather than near the equator. This presents a unique and difficult challenge, which Draper is helping to solve.

“The angle of light from the Sun is very low,” Paceley outlined. “So you have a lot of shadows and dark spots. Being able to land safely is a big challenge for this program. We have to provide the capabilities to enable the astronauts landing safely, whether that’s particular sensors that we use to navigate with or with some synthetic vision to allow them to see the boulders, the craters, so they they can avoid those as the vehicle lands. The nice thing about where we are today is we did that 50 years ago on Apollo, but technology has come so much farther now in terms of computers and sensors and electronics — the solutions you can apply to that problem.”

Villarreal added, “One of the exciting things we’ve been able to provide to help visualize the tough landing situation is a lunar lander simulator that’s based at Dynetics.”

“What that does is loop in our guidance, navigation, control algorithm tied to hand controllers for users to specifically stand in the simulator and act as though they are landing the descent/ascent lander element while visually seeing a representation of the lunar surface projected up over a dome,” she said. “So it really brings home the challenges of that lighting situation.”

“Astronaut-pilots (during Apollo) like Neil Armstrong could look out the window, control the vehicle and decide where they wanted to land in a safe area,” Paceley remarked. “Now, there’s a lot more emphasis on autonomy. While the astronauts can take over and pilot the vehicle, we are putting in a lot more autonomy so that the vehicle can do much of the landing on its own — and even, if need be, could land on its own if there were not a pilot on board — and do so safely.”

Hendrix told Yellowhammer News that Draper has been great to partner with. Overall, including Draper, Dynetics in assembling its HLS team sought out “the best companies available” of all sizes.

“We’re just glad they’re a part of it,” she concluded.

Sean Ross is the editor of Yellowhammer News. You can follow him on Twitter @sean_yhn